Language comes later for siblings of children with autism

Infant siblings of children with autism tend to lag behind their peers at the earliest stages of language development before catching up at around 12 months of age.

|

Baby babble: Putting together vowels and consonants is an important aspect of language acquisition, which is slow to develop in siblings of children with autism. |

Infant siblings of children with autism tend to lag behind their peers at the earliest stages of language development before catching up at around 12 months of age, according to a study published online in October in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry1.

Children who have a sibling with autism are known to be anywhere between 3 and 20 percent more likely to develop the disorder2 compared with typical controls.

The new study found that the siblings also tend to acquire certain consonants more slowly, combine consonants and vowels less frequently in babble and early words, and retain non-speech vocalizations, such as growls and yells, longer.

The researchers also found some correlation between immature language development at 9 months and the likelihood of an autism diagnosis at 24 months. Nearly a third of the high-risk infants with delayed language received a provisional autism diagnosis when assessed at 24 months. One in four of the children were diagnosed with broad autism phenotype (BAP), sharing some traits of autism in a milder form.

Still, counting the number of consonants a child articulates in the first year of life is not likely to become an early marker for autism, says lead investigator Rhea Paul, director of the Laboratory of Developmental Communication Disorders at the Yale Child Study Center.

“I don’t think these differences are going to be diagnostic, because while the high-risk children have some difficulties in acquiring these things, they do get there eventually,” Paul says.

A child can also show symptoms of language delay and autism at 24 months but look perfectly fine a year later, she points out. “What parents need to know is that children are very resilient,” she says. “Development is a variable process.”

The researchers collected speech samples from high-risk siblings and low-risk controls — roughly 30 each — at 6, 9 and 12 months. They also assessed a subset of 24 high-risk siblings and 21 low-risk controls for autism, BAP and developmental delay when these same children reached 2 years of age.

Paul, a speech pathologist who has spent more than a decade studying late-talkers — children aged 18 to 30 months who haven’t yet started using words — didn’t expect to find much difference between the autism siblings and others at this pre-linguistic stage of development. “I assumed that any differences would emerge after 12 months,” she says. “To my surprise, we found differences in the first year.”

Consonant challenge:

The total number of vocalizations is similar between the two groups, and increases over time with age. However, at every age, children in the high-risk group produce fewer speech-like vocalizations than the low-risk controls do. “The children who were at high risk because of an older sibling with autism tended to use a less mature set of sounds,” says Paul.

Sounds are acquired in a well-characterized order, she says, with certain consonants such as b, d and m appearing earlier than, for example, s, r and z. Appearance of the later-developing consonants is delayed in the high-risk group.

The way they put consonants and vowels together is also less mature, Paul says, with the high-risk children producing fewer canonical syllables — those that, like ‘ba,’ include both a consonant and a vowel — at 9 months of age.

Between 6 and 12 months of age, the high-risk children also growl, yell and use other pre-verbal vocalizations more than do the low-risk children, who largely abandon those sounds as they transition into language.

At 24 months, the researchers found that those who produce fewer middle consonants at 6 months, late consonants at 9 months and total consonants at 12 months are more likely to receive a diagnosis of autism or BAP.

These results are consistent with findings from the LENA system, an automated tool used to detect distinctive speech patterns in children with autism3, says David Kimbrough Oller, professor of speech language pathology at the University of Memphis, who worked as a consultant with the LENA team.

“The basic idea that there are going to be ways that you can look at the vocal system of the children with autism and differentiate them fairly early from typically developing kids is completely consistent with our LENA findings, which are based on 23,000 hours of recording,” he says.

Identifying these patterns in the infant siblings of children with autism is both plausible and novel, he says, and Paul’s study has set the bar for other groups studying this phenomenon.

“They are the first ones who have gotten the job done, getting something out on vocal development in sibling of children with autism on any scale. They will be the standard to meet on this topic for a while.”

The findings also agree with other emerging work in the high-risk population, adds Helen Tager-Flusberg, director of the laboratory of developmental cognitive neuroscience at Boston University.

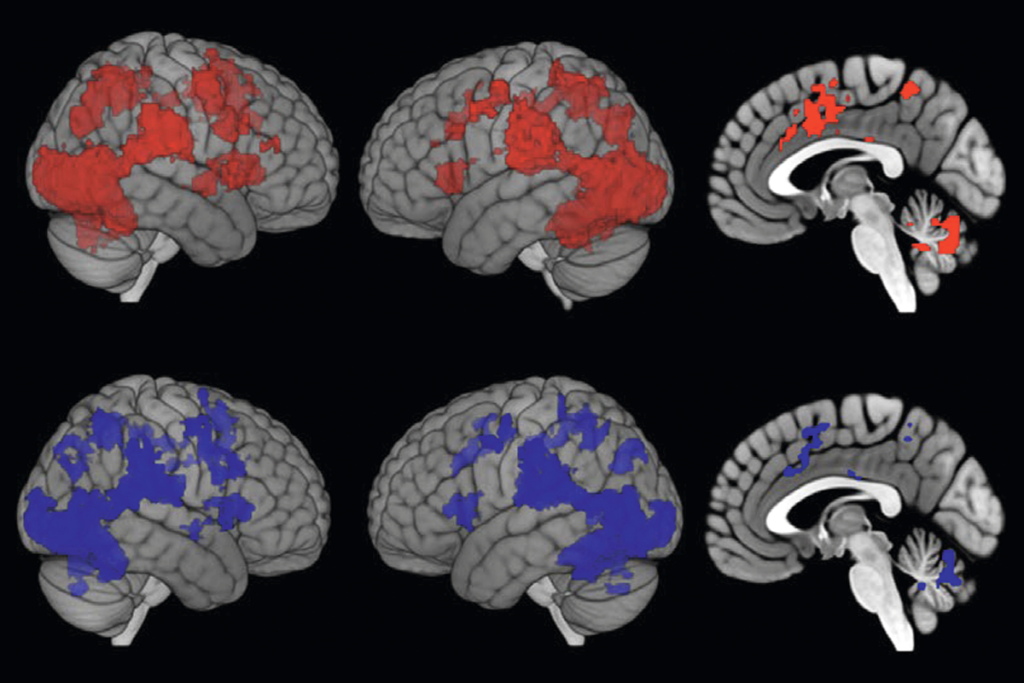

“By 9 months, we are clearly able to differentiate high- from low-risk infants,” she says. “The jury is still out on 6 months or younger. It will be interesting to see how early the genetic risks show up in either brain signatures or behavioral patterns.”

References:

Recommended reading

Cell ‘antennae’ link autism, congenital heart disease

Neurophysiologic distinction between autism and schizophrenia; and more

Four autism subtypes map onto distinct genes, traits

Explore more from The Transmitter

Human brain may anticipate looming contagion

What U.S. science stands to lose without international graduate students and postdoctoral researchers