Dampening the expression of an autism-linked gene in a small part of the brain in adult female zebra finches makes the birds less interested than usual in the songs of male zebra finches, according to a new study.

The findings suggest the gene, FOXP1, is involved in motivation to listen to social communication of other members of one’s species.

Alterations in the FOXP1 gene in people are associated with language impairments and autism. Songbirds have become models for studying the genes and neural pathways involved in language learning because they are among a handful of animal groups that exhibit vocal learning: Young birds learn to sing by listening to and imitating an adult bird, much as children learn to speak by listening to and imitating others. Among zebra finches, only males sing, and FOXP1 is crucial for them to learn their songs.

Most previous studies of FOXP1 and related genes in songbirds have focused on sensorimotor integration and the motor aspects of song production, says study investigator Simon Fisher, director of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Studying female birds “made it possible to tease out potential impacts of FOXP1 disruptions on sensory aspects; this revealed consequences for auditory learning, involving perception and motivational behaviors, and independent of motor production aspects of song,” he says.

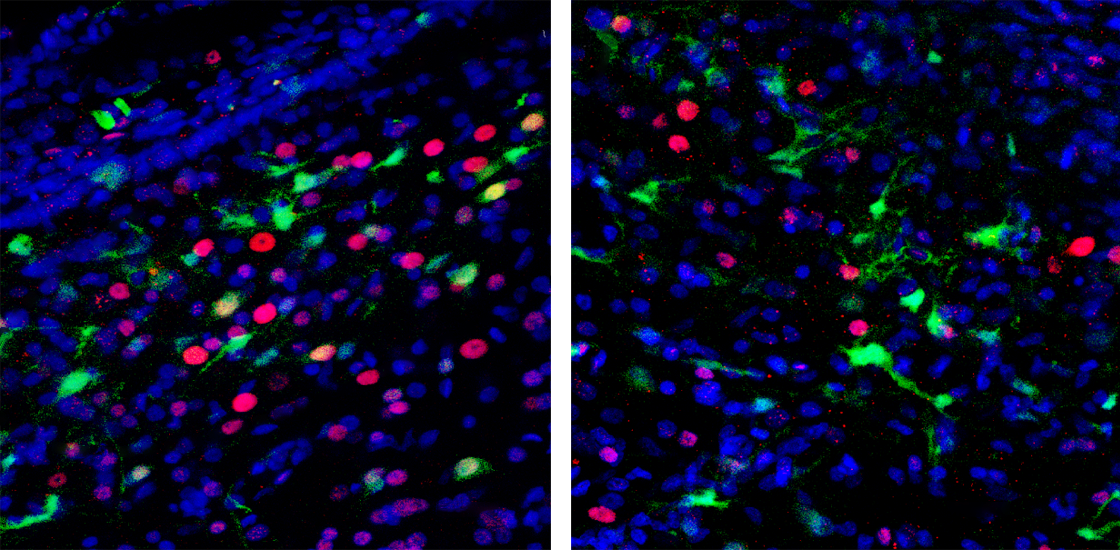

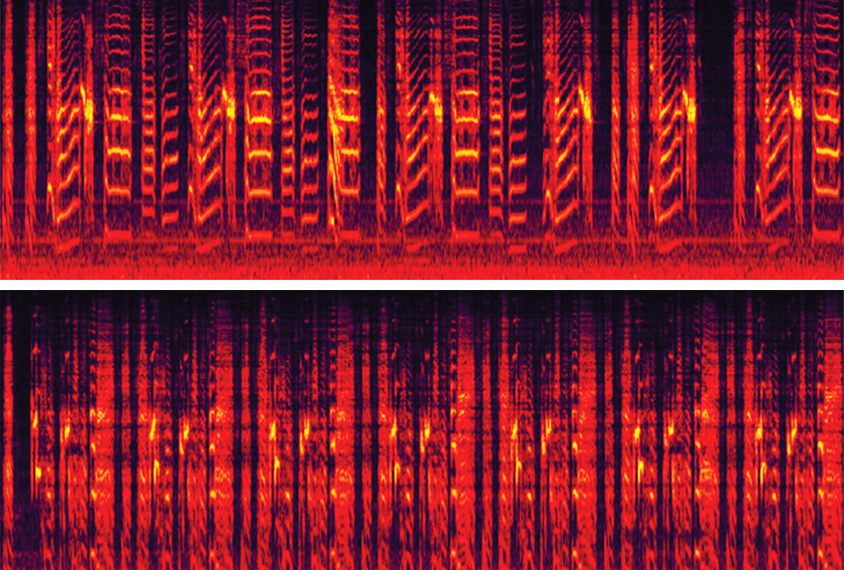

A

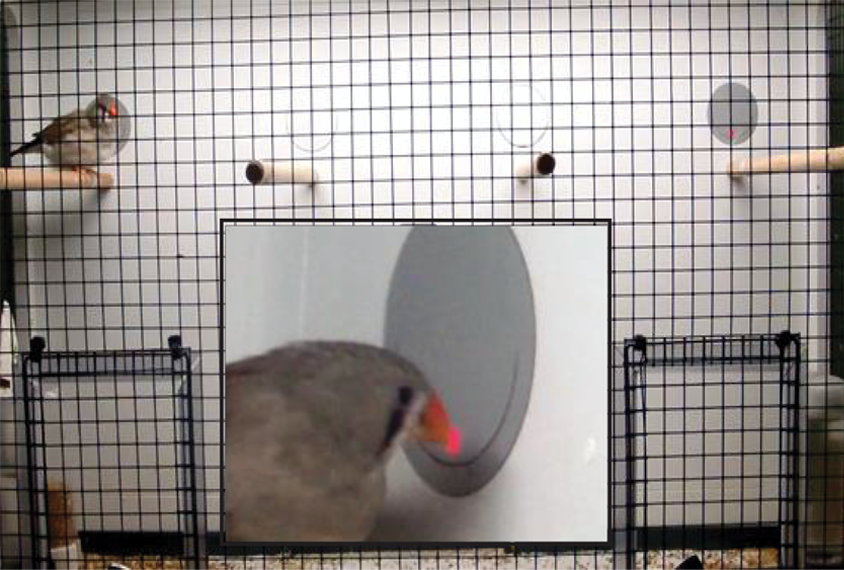

lthough female zebra finches do not sing, they form memories of songs heard early in life. In the new study, researchers used a genetically engineered virus to dampen FOXP1 expression in both juvenile and adult female zebra finches, before and after the sensitive phase for song memorization. They delivered the treatments to one of two brain areas that contribute to auditory processing and song memorization and have high levels of FOXP1 expression: the HVC or the caudomedial mesopallium (CMM).As adults, the birds showed their listening preferences by pecking at two electronic buttons in a cage. One button triggered playback of the song sung by the bird’s father, and the other played a song with similar characteristics that the bird had never heard before.

Zebra finches are curious and social, and some of them figured out how the song playback worked all on their own, says study investigator Fabian Heim, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence in Seewiesen, Germany. Others needed a handful of training sessions, sometimes with a grain of millet — a favorite food — taped to the buttons to pique their interest.

“You can really see when it clicks,” says Heim, who conducted the work as a graduate student in Katharina Riebel’s lab at Leiden University in the Netherlands. “As soon as they get it, they’re wild for it.”

All 96 female birds in the study learned the pecking task and preferred to hear the familiar song, regardless of whether, when or where FOXP1 had been manipulated in the brain, the researchers reported last month in eNeuro. But birds that experienced dampening of FOXP1 expression in the HVC as adults pecked less at the buttons overall and had a weakened preference for the familiar song.

The fact that the birds could learn and still had a significant preference for familiar song suggests that problems with motivation, and not learning or hearing, explain the results, Heim says.

“It’s sort of a surprising finding,” Jon Sakata, associate professor of biology at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, who was not involved in the work, says of the study’s link between FOXP1 and motivation. “It’s a very different take on FOXP1.”

T

he researchers had expected to see more of an effect from altering FOXP1 in juvenile rather than adult birds, Heim says. It may be that in young birds, other related genes can compensate for the lower activity of FOXP1, he suspects.Dampening expression of FOXP1 in the HVC impairs the ability of young male zebra finches to encode song memories, a 2021 study showed. The new work “builds on and further expands” these findings, says Constantina Theofanopoulou, associate research professor at Hunter College of the City University of New York, who was not involved in either study. In juvenile females, dampening FOXP1 expression in the HVC does not affect motivation to listen. “If the same applies in juvenile male finches, then we have at least narrowed down on the list” of what aspects of song learning FOXP1 affects, she says.

But because the effects on song preferences were only seen in females that had FOXP1 expression dampened in adulthood, after the sensitive period for song memorization, FOXP1 may not necessarily affect processes occurring during song learning, Sakata says.

Still, the study illustrates the usefulness of studying the non-singing sex, says Sarah Woolley, associate professor of biology at McGill University, who was not involved in the work. Female zebra finches listen to songs to parse social relationships between other birds in the flock and identify promising suitors, so they may help illuminate the details of social communication. “We know that female birds are really attuned to those kinds of signals,” Woolley says.

Simply comparing a bird’s response to her father’s song versus an unfamiliar one, as in the current study, may not fully encompass these subtleties, Woolley says. Heim also has data on the effect that dampening FOXP1 has on a variety of other cognitive skills in the female birds, which he aims to publish in the future, he says.