Lack of DNA modification creates hotspots for mutations

The absence of a chemical alteration called methylation on some stretches of DNA makes them especially prone to mutations, according to a paper published in PLoS Genetics in May.

The absence ofa chemical alteration called methylation on some stretches of DNA makes them especially prone to mutations, according to a paper published in PLoS Genetics in May1.

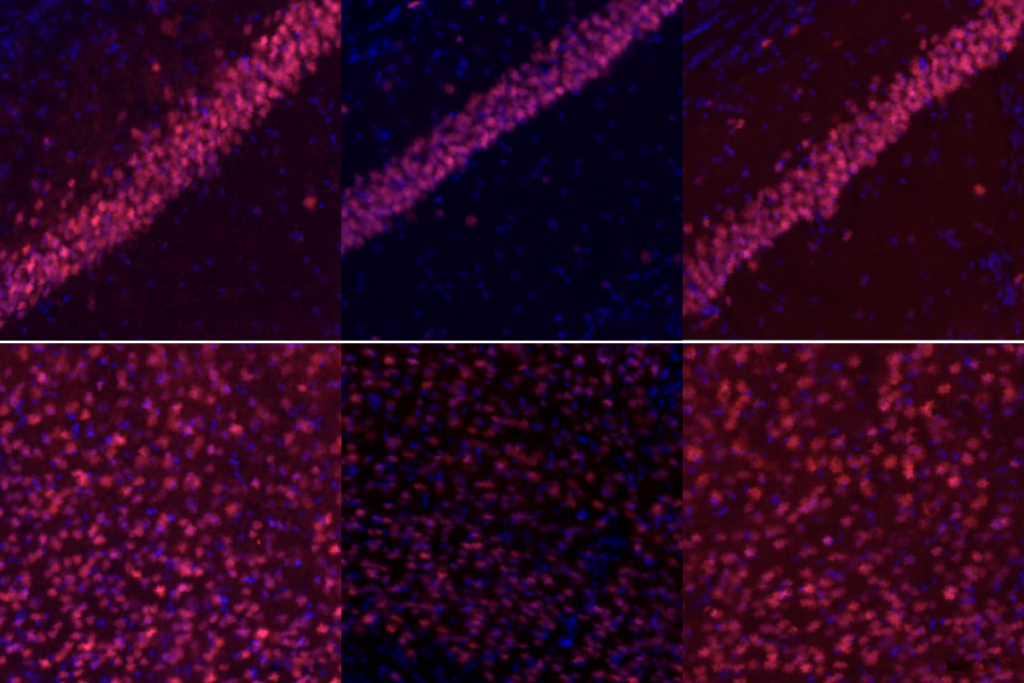

Studying DNA from human sperm, the researchers found that areas of the genome that lack methyl groups — modifications that can alter gene expression without changing the DNA sequence — are afflicted by mutations more often than highly methylated regions.

“Most of the genomic DNA was methylated, but a small percentage was not,” says lead investigator Aleksandar Milosavljevic, associate professor of molecular and human genetics at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. “What was very striking was that the part that was not methylated contained signs of high genomic instability.”

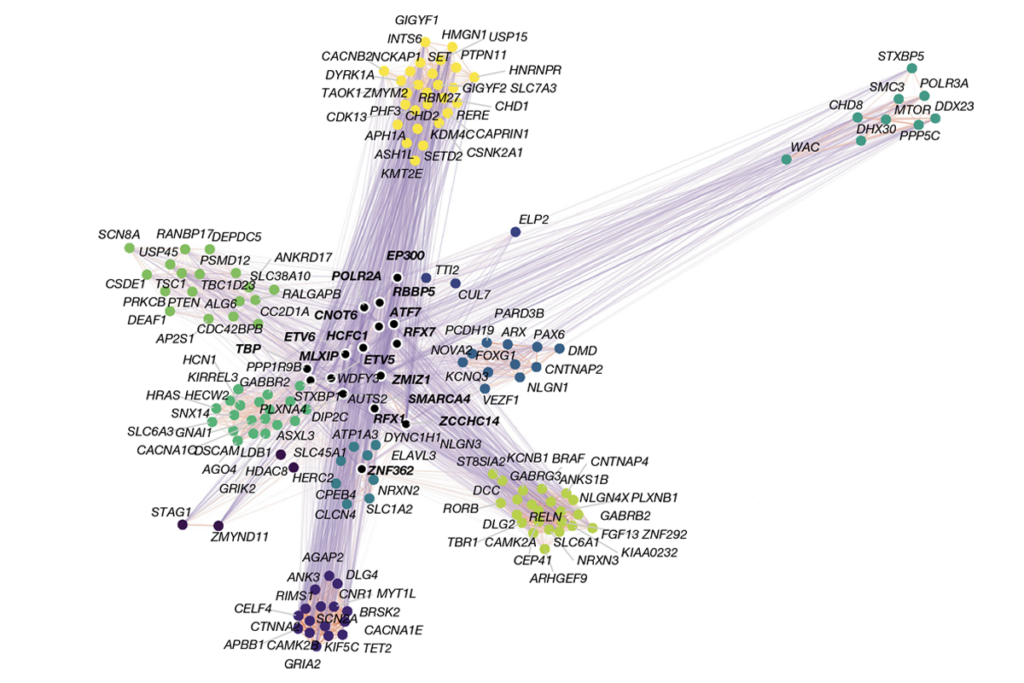

In particular, these so-called methylation deserts are spotted with copy number variations (CNVs), deletions or duplications of a length of DNA. Because some of the most well-documented genomic links to autism are CNVs, the new findings might help clarify the disorder’s genetic origins.

Scientists had already known that parts of the genome with low-copy repeats — short, repeated segments of genomic DNA — are particularly susceptible to CNVs. The new research shows that lack of methylation may be just as influential, and is the first to make the connection between methylation and structural mutations of the genome.

Comparing human, chimpanzee and other primate genomes, the researchers found that more than ten percent of changes to the human genome since we branched off from chimps six million years ago reside in the least methylated part of the genome. Even from person to person, they found more mutations overall, including CNVs and other types of mutations, in hypomethylated regions than elsewhere in the genome.

Methylation deserts:

Several studies in the past few years have reported rare mutations linked to various neuropsychiatric conditions. Analyzing data from four recentstudies on CNVs — including 3,391 individuals with schizophrenia, 1,001 with bipolar disorder, 996 with autism spectrum disorders and 15,767 children with developmental delay — the researchers found that people with any of the four disorders have more CNVs than controls have in the hypomethylated regions of their DNA.What’s more, in each case, a number of known pathogenic CNVs appear in the hypomethylated regions.

“We’re not providing any answers for understanding disease etiology, but we’re opening up a new line of inquiry,” Milosavljevic says.

Changes in methylation patterns have previously been linked to autism, but the precise nature of these patterns is not yet clear. A study published last December found that postmortem brains from people with autism have more methylation in some parts of the genome and less in others, compared with control brains. Some genes linked to autism have been found to be highly methylated and MTHFR, or methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase,a gene that controls methylation, has been tied to a higher risk of autism.

The decrease in methylation in people with autism found in the new study may explain why they have more CNVs than controls do.

Some children with autism have parents who have other neuropsychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder, says Simon Gregory, associate professor of medical genetics at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who was not involved in the research. “If [the researchers] are able to identify a relationship between these methylation deserts and CNVs in these other disorders, we might be seeing a common mechanism.”

It’s possible that these families are more vulnerable to mutations because the relevant regions of their genomes are less methylated. A second potential mechanism is the build-up of CNVs that occur spontaneously rather than being passed down through generations. These sorts of de novo mutations are thought to be important in autism and other psychiatric disorders. If a single CNV in a parent raises the risk for a psychiatric disorder, a second spontaneous CNV in the child might raise the risk for a more serious impairment, such as autism.

The new research begins to answer some longstanding questions, but it leaves many others up for debate. “Ten percent of the rearrangements occur in the methylation deserts, but 90 percent occur elsewhere,” Gregory says. “Perhaps it’s answering 10 percent of the problem, but that still leaves the other 90 percent.”

References:

1: Li J. et al. PLoS Genet. Epub ahead of print (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

Post-infection immune conflict alters fetal development in some male mice

In-vivo base editing in a mouse model of autism, and more

Organoid study reveals shared brain pathways across autism-linked variants

Explore more from The Transmitter

Dendrites help neuroscientists see the forest for the trees