IQ scores not a good measure of function in autism

Most studies define high-functioning children as those with an IQ above 70 or 80, but this is problematic for a number of reasons, say some scientists. The assumption underlying the use of high IQ as a synonym for high functioning is suspect because social and communicative abilities may have a far greater impact on an individual’s daily interactions.

A few years ago, Annette Estes was recruiting children with autism for a study relating intelligence quotient (IQ) scores to academic achievement. Among the recruits, Estes recalls, was a child who was excluded from the study both because she was non-verbal and because she acted out severely during the interview.

“When we were finished, she drew a rainbow, which she labeled ‘My rainbow’ and then began trading messages with her mom about going to McDonald’s,” recalls Estes, who is research assistant professor of speech and hearing sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. “We couldn’t assess her reading skills in the way you need to do for a study like this, but she was clearly able to read and write.”

Children like this are unlikely to be included in cognitive and behavioral studies that focus increasingly on ‘high-functioning’ individuals with autism. Most studies define high-functioning children as those with an IQ above 70 or 80, but this is problematic for a number of reasons, say some scientists.

Researchers don’t all use the same test to measure intelligence, for one thing, and even when they do, IQ thresholds often vary among studies.

The assumption underlying the use of high IQ as a synonym for high functioning is also suspect because social and communicative abilities may have a far greater impact on an individual’s daily interactions.

“Crudely taking IQ as a metric to divide up individuals can be misleading, because high-functioning sounds like you are doing really well, when in fact you’re not,” says cognitive psychologist Tony Charman, professor of autism education at the University of London.

In an ongoing study of 100 children between 14 and 16 years of age in the U.K., he and his colleagues are trying to identify cognitive subtypes of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Early analyses of their data show that there is no evidence as yet for a different cognitive phenotype in individuals with high IQs compared with those who have a low IQ1.

Cognitive dissonance:

IQ scores generally relate to the ability to communicate or to adapt to daily life, but they are far from perfect indicators of cognitive, much less global, functioning, Charman says.

Estes’ experience reinforces that point. Her study sample of 30 children was drawn from a larger group of children enrolled in a longitudinal study when they were 3 or 4 years old. “There was no focus on any cognitive level in the larger study,” she says. The only criterion for inclusion was having received a diagnosis on the autism spectrum.

As the children aged, however, functional differences emerged. By the time the children were 9, the researchers found it difficult to carry out standardized assessments in some of the children, either because they were non-verbal or because “they didn’t respond to paper-and-pencil assessments,” Estes says.

At the same time, it was clear that some of those children were quite intelligent. One child who was unable to complete the index task to enter the study quickly answered all of the math problems on his own initiative.

Researchers may choose to study ‘high-functioning’ individuals not only because they are more cooperative and better able to complete testing, but also because they believe that weeding out individuals with intellectual disability will provide more pure results, Charman says.

“There is some notion that you are getting this uncontaminated look at autism if you strip away intellectual disability, even though intellectual disability is present in half of individuals with autism,” he says.

However, intellectual disability as measured by IQ scores can vary, depending on the test used. Non-verbal children, for example, garner low scores on verbal IQ tests but may score at an age-appropriate level on tests of spatial intelligence.

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, commonly used in autism studies, gets around this difficulty by returning scores for both verbal and non-verbal, or performance, IQ, which can be further broken down into more discrete categories.

But if researchers use different tests or different thresholds to define high-functioning individuals, it becomes more difficult to compare results across studies.

Real skills:

Regardless of the test, IQ may not be the best indicator of the ability of a person with autism to navigate the real world. “An individual’s level of functioning can more impacted by co-morbid mental health problems than by IQ — and this is particularly true for adults,” says Peter Szatmari, head of child psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at McMaster University in Ontario.

A person who scores 125 on an IQ test — and thus considered high-functioning — may in fact be considerably impaired in daily activities.

Levels of functioning can also change over time, Szatmari points out. In a multi-site Canadian study called Pathways, he and colleagues are looking at how children with autism progress from diagnosis through grade 1 and, ultimately, grade 6.

The team is seeing astonishing variability in both language skills and behavior in the 18 to 24 months following diagnosis, he says. “There’s so much change that the IQ tests can’t capture the diversity of kids.”

Even in the very limited arena of academic achievement, IQ may be less relevant than is commonly assumed. For example, Estes’ study, published 2 November in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, reports that IQ does not accurately predict academic performance in most high-functioning children with autism in regular classrooms2.

Some did better on spelling and reading tests than their IQ would predict and some did worse, even though IQ is tightly tied to academic achievement in healthy children. What’s more, children in the study who had better social skills at age 6 showed higher levels of academic achievement at age 9, regardless of IQ.

A population study of more than 8,000 twin pairs in the U.K. published in February looked at the association between autism traits and intelligence in 145 children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder by age 7. Autism traits and intelligence were both stable over time, but there was only a modest association between the two, suggesting that autism traits are independent of intellectual functioning3.

There is nothing inherently wrong in studying individuals classified as high-functioning rather than a more diverse population of people with autism, Charman says. Still, he adds, “people need to be cautious and remember that it’s not a cut that represents some true boundary in nature.”

With reporting by Karen Patterson

References:

Recommended reading

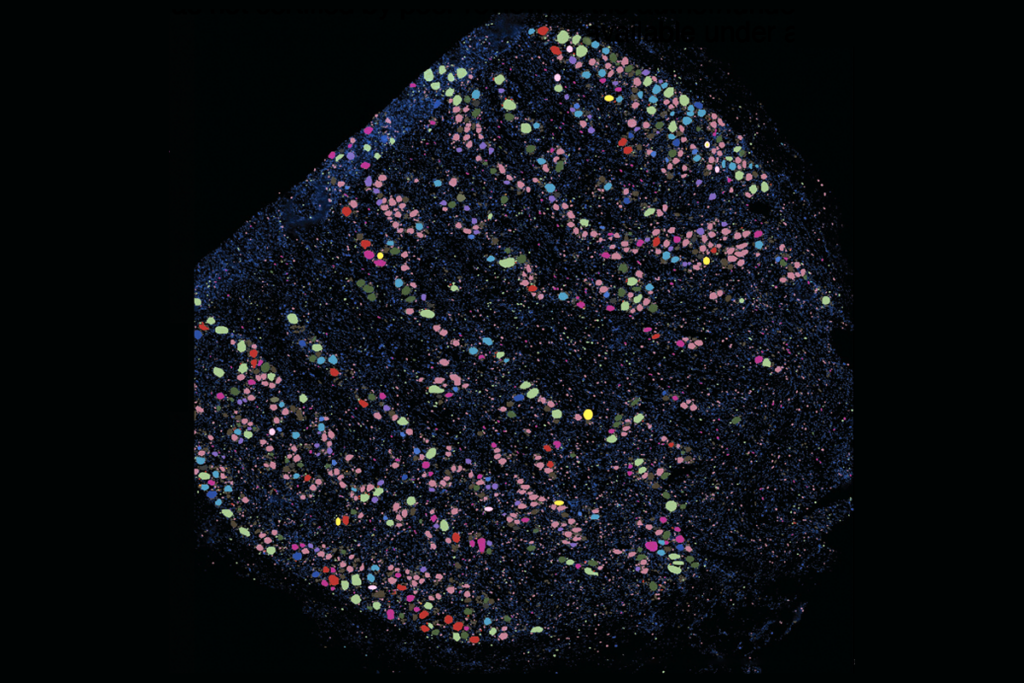

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models