Inflammation in mother tied to child’s brain function, behavior

Brain networks in newborns may reflect the degree of inflammation their mothers experienced during pregnancy.

Brain networks in babies reflect the degree of inflammation their mothers experienced during pregnancy, according to a new study1. A mother’s immune response also tracks with her child’s cognitive abilities at age 2.

The findings support the hypothesis that in-utero exposure to inflammation shapes brain development and boosts the risk of conditions such as autism and schizophrenia.

The new work provides an empirical look at the influence of the maternal immune system on children, says lead investigator Damien Fair, associate professor of behavioral neuroscience and psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University. Most previous work on this link is limited to animal studies and observational reports.

“Being able to directly show it in this way in [the] brain and then, of course, relating it to future behavior [in humans] is new,” Fair says.

The findings mesh with some evidence from animal models, such as studies in mice revealing receptors for inflammatory molecules in the fetal brain, says Dan Littman, professor of molecular immunology at New York University, who was not involved in the study. But more research is needed to map out a mechanism linking maternal inflammation to changes in the developing brain.

“At the end of the day, everything is still correlative,” Littman says. “How these two are connected, we don’t really know.”

Baby brains:

Fair and his colleagues measured levels of the inflammatory molecule interleukin-6 (IL-6) in blood collected from 84 women during each trimester of pregnancy. They scanned the brains of the women’s babies at around 4 weeks of age.

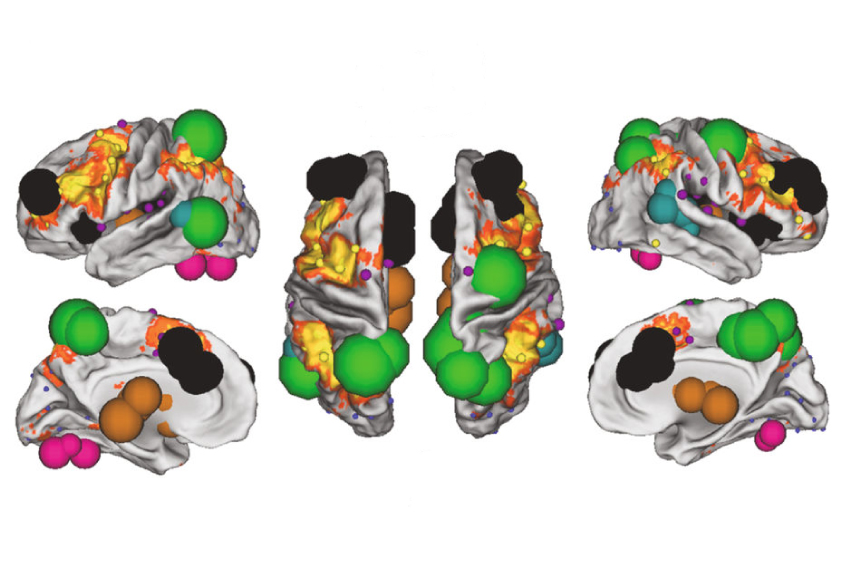

Specifically, they looked at functional connectivity, a measure of the extent to which brain regions are active together. The researchers put connectivity data for 68 of the babies into a machine-learning algorithm alongside their mothers’ IL-6 levels and tested the model with data from the remaining 16 babies. They repeated this process thousands of times using data from different sets of the babies.

Patterns of connectivity within each infant’s salience network — which decides what stimuli deserve a person’s attention — predict her mother’s average IL-6 levels during pregnancy, the team found.

They also found that maternal IL-6 levels track with connectivity between the salience network and another attention network, and between the dorsal attention network and other regions in the brain. The results appeared 9 April in Nature Neuroscience.

The findings suggest that typical variation in inflammation, not just severe infections such as the flu, during pregnancy influences brain development in the child, Fair says.

When the children were 2, the researchers gave 46 of them a task assessing working memory, the ability to hold information in mind for short periods of time. They found that the higher a mother’s IL-6 levels during pregnancy, the lower her child’s scores on the test.

However, it’s unlikely that inflammation in the mother only affects the child’s working memory, says Alan Brown, professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University, who was not involved with the work. In a 2009 study, Brown’s group found that infection in a pregnant woman hinders her grown child’s ability to switch between tasks2. (The adult children in this study all have schizophrenia.)

The new study shows that cognitive problems may present in early childhood. “Now you’re actually showing an effect directly on neurodevelopment, so it kind of fills in an important missing piece of puzzle from our study,” he says.

Cognitive connection:

The new work also points to the brain regions involved. The connectivity patterns that best predict the mothers’ IL-6 levels include many areas implicated in working memory.

The study’s results jibe with those of a January study using the same sample. In that study, the team discovered that an increase in IL-6 during pregnancy corresponds with greater connectivity between the amygdala and several other brain regions in newborns. It also tracks with a decrease in impulse control in the children at age 23.

Similarly, in a study published in March, a separate team observed a correlation between teenage mothers’ IL-6 levels and brain connectivity in their newborns’ salience networks4. However, that study found that higher levels of IL-6 are associated with better performance on a test of cognitive skills at 14 months.

Differences between the cognitive tests used in the studies could explain this discrepancy, Fair says.

Identifying the triggers of inflammation in pregnancy may help researchers understand how it affects development. The team is exploring how diet alters the mother’s immune system and, in turn, the brain organization and behavior of children.

References:

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain