Some preterm babies who are later diagnosed with autism show increasing developmental delays during infancy, according to a new study1.

This distinct pattern could help doctors identify autism in preterm babies and start them on therapies in infancy, says Li-Wen Chen, pediatric neurologist at National Cheng Kung University College of Medicine in Taiwan, who designed and conducted the study.

About 7 percent of children born preterm are autistic, compared with 1 to 2 percent of children in the general population. Researchers cannot accurately predict which preterm babies are most likely to be later diagnosed with the condition, however.

The new study tracked ‘very preterm’ babies — meaning those born more than 8 weeks prematurely and weighing 3.3 pounds or less — from birth to 5 years old. It shows that preterm autistic babies’ development deviates significantly from that of their non-autistic peers starting at 6 months of age. This split could flag preterm babies in need of behavioral interventions well before the typical age of an autism diagnosis, which is about 4 years in the United States.

“This early trajectory work is really very valuable, because it means you shouldn’t be making predictions based on single observations,” says Neil Marlow, professor of neonatal medicine at University College London in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the work.

Autistic children who are born preterm score lower on measures of nonverbal behaviors important for social interactions than do autistic children who are born full-term, according to previous work by Chen’s team2. Those results also showed that autism traits are more similar among preterm children than among full-term children.

Together, the earlier findings suggested that preterm autistic children share early developmental markers of autism, Chen says. For the new work, she and her team set out to identify such markers.

Low-declining:

Chen’s team followed 319 infants born before the 32nd week of pregnancy from 2008 to 2014 in Taiwan. They measured the children’s cognitive, language and motor skills at 6, 12 and 24 months of age using a test called the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. They also collected data on parents’ education levels and any complications the children experienced as newborns, such as lung infections or internal bleeding.

When the children were 5 years old, researchers assessed them for autism using a clinician-administered diagnostic tool; they diagnosed 29 children with the condition.

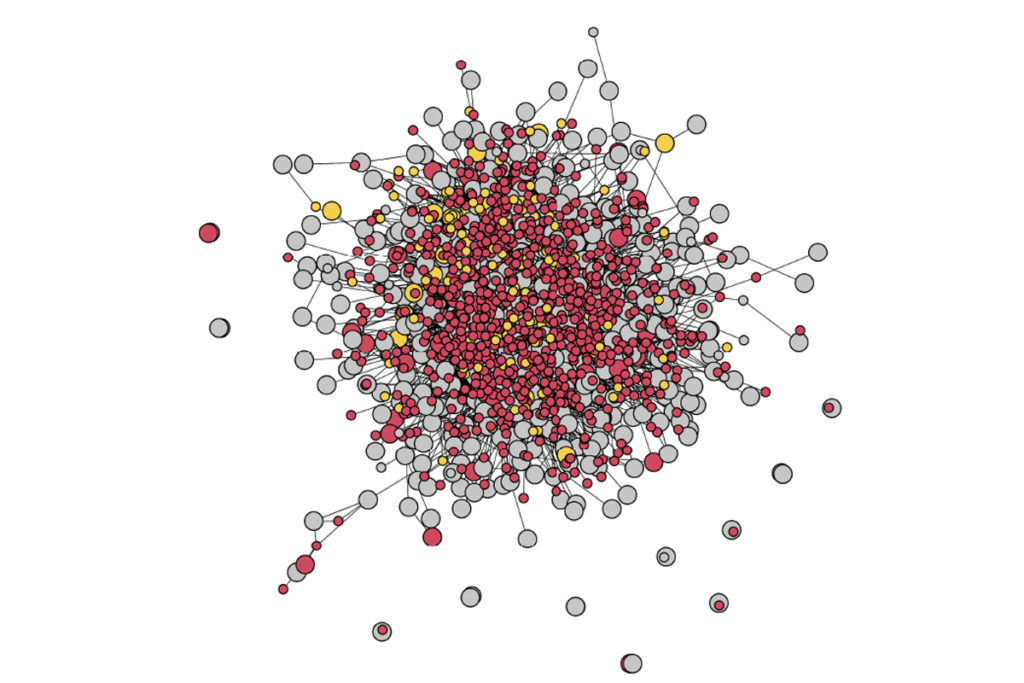

The children cluster into three distinct groups, based on how their Bayley scores shifted from age 6 months to 2 years: 31 percent started and ended with high scores, which reflect typical development; 62 percent started with high scores that decreased slightly from 12 to 24 months of age; and the remaining 7 percent started with low scores that plummeted further after 12 months.

Children in the ‘low-declining’ group have the highest odds of having autism: About 35 percent were diagnosed with the condition by age 5, the researchers found. By comparison, autistic children compose just 9 percent of the group that started high and dropped in score, and 3 percent of the group whose scores remained stable.

Put another way, children in the low-declining group were 15 times as likely to be diagnosed with autism by age 5 as were children in the ‘high-stable’ group. Compared with the other groups, the low-declining group also scored higher on measures of autism traits, including social communication and restricted and repetitive behaviors. The findings were published in September in Pediatrics.

This developmental trajectory could flag a preterm baby’s elevated chance of having autism for pediatricians and parents, and prompt them to seek early diagnosis and interventions to help ease cognitive and behavioral issues, Chen says.

“I really like the trajectory analysis,” says April Benasich, professor of developmental cognitive neuroscience at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, who was not involved in the work. This long-term tracking is especially important when it comes to preterm children, she says, as they have a considerably higher incidence of developmental issues, such as language impairment.

Untangling causes:

Children in the low-declining group tend to be boys and to have received oxygen therapy for a prolonged period at birth, the study shows. They are also more likely to have mothers who did not attend college or graduate school. Oxygen toxicity could potentially influence an infant’s developmental trajectory and likelihood of getting an autism diagnosis, because it is associated with visual and respiratory complications, Chen says3.

The duration of oxygen therapy can also be a proxy for neonatal complications such as brain bleeding that can influence a child’s development. Although the researchers did assess many complications, they did not consider brain bleeds, which could have helped explain the results and should have been included, Benasich says.

The effects of preterm birth may cause widespread changes in an infant’s brain that lead to the observed delays and traits that look like autism but are not, Benasich says.

“I was a little concerned that this social communication and these repetitive behaviors can be due to not [autism] per se as they diagnose it, but sort of global deficits in cognition due to biological damage in these smaller babies. And there are more smaller babies in this low-declining group,” she says.

Specifically, 44 percent of the infants in the low-declining were smaller than average for their gestational age, compared with 19 percent in the high-declining group and 17 percent in the high-stable group.

Chen’s team plans to follow up on this work by looking at which prenatal and neonatal factors are linked to an autism diagnosis. They also plan to perform brain imaging in search of early biomarkers.