In mouse model of Rett, immune cells overly sensitive

Loss of MeCP2, the Rett syndrome gene, depletes immune cells throughout the bodies of mice, researchers reported yesterday at the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Loss of MeCP2, the Rett syndrome gene, depletes immune cells throughout the bodies of mice, researchers reported yesterday at the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

These immune cells, including microglia — which are specific to the brain — are abnormal and prone to be hypersensitive to cell damage.

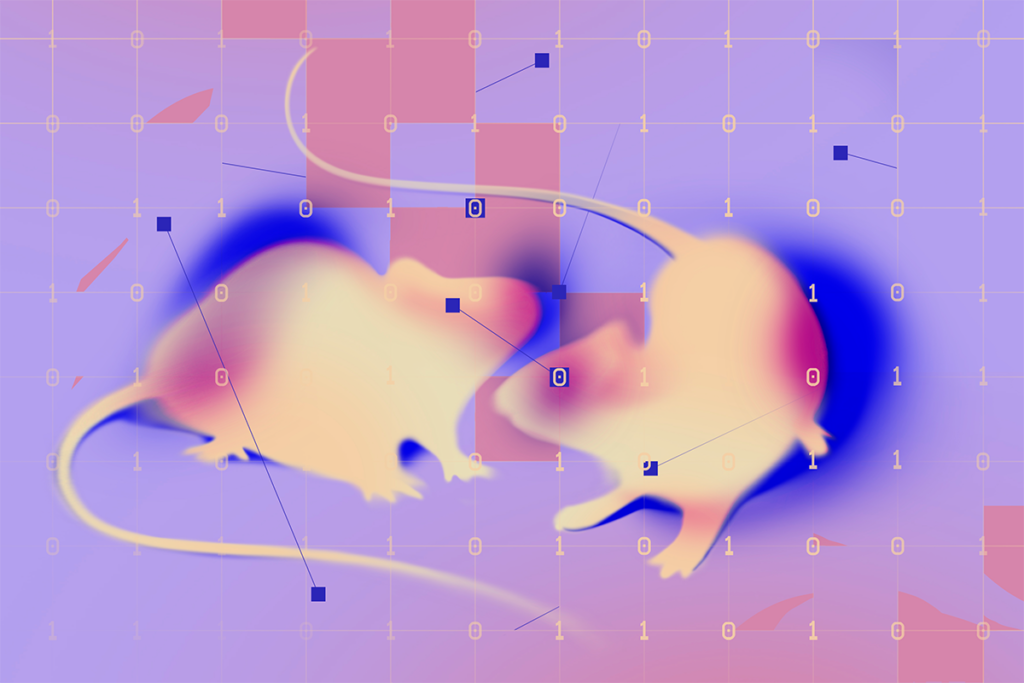

The results provide a mechanistic basis for a study published in 2012, which showed that a bone marrow transplant lengthens Rett mice’s lifespan and improves some of their symptoms.

The mice only improved if the irradiation included the brain, suggesting that the key benefit came from microglia — which derive from the bone marrow.

But this was just speculation, notes Jim Cronk, a graduate student in Jonathan Kipnis’ lab at the University of Virginia, who presented the findings in a poster session. “Even though we were able to show that the transplant increases survival, we didn’t know exactly what it was doing in the brain,” he says.

In the new study, the researchers engineered mice so that they could restore MeCP2 expression in microglia and other immune cells after the onset of symptoms. These mice live about three months longer than other Rett mice, equivalent to the benefit from the bone marrow transplant. The researchers also confirmed that microglia make MeCP2, traditionally believed to be a neuronal protein.

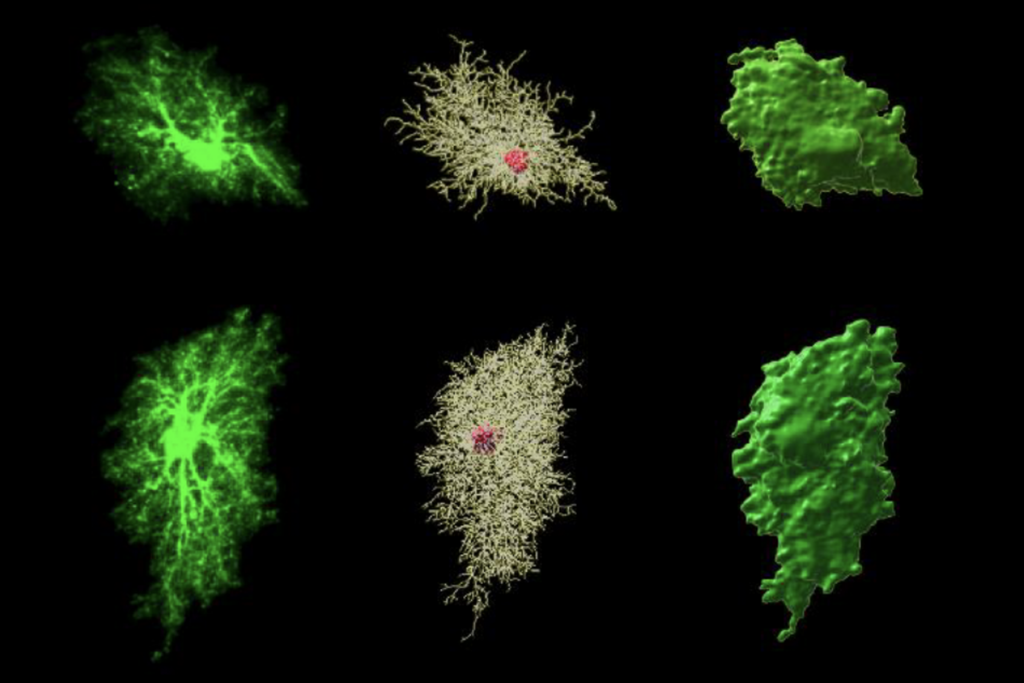

They then looked in detail at microglia from mice lacking MeCP2. These cells look abnormal, with atypically large cell bodies and few branches — as such cells do when they are inflamed.

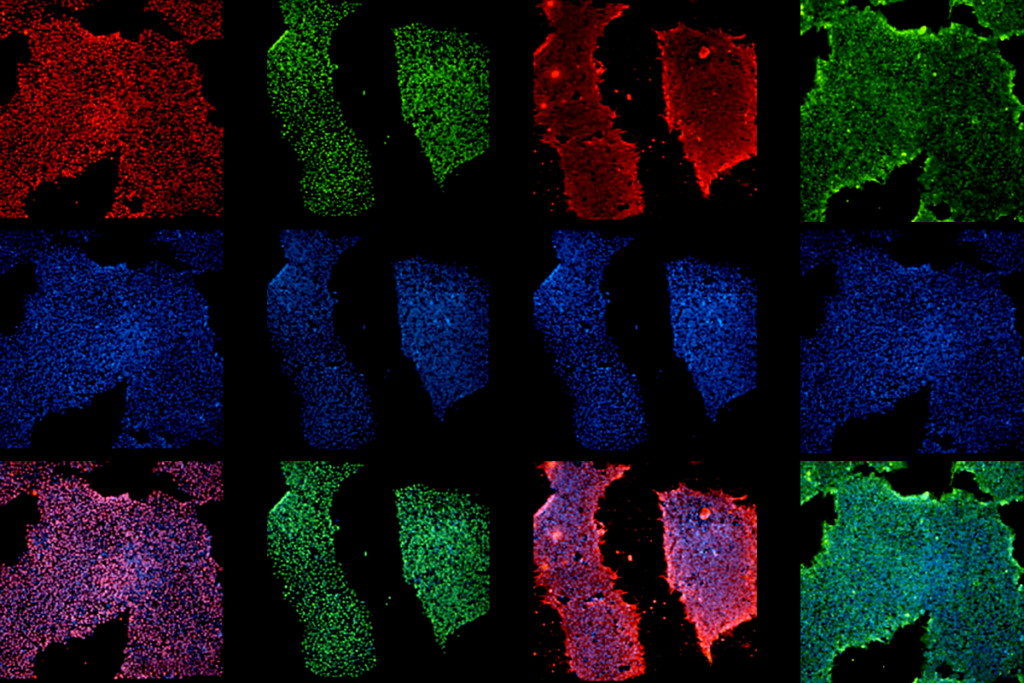

Lack of MeCP2 also affects immune cells located elsewhere in the body. In particular, the mice have abnormal macrophages in the bone marrow and in their intestinal lining.

These changes occur only after the mice show symptoms, notes Cronk. Eventually, the mice lose about one-third of their microglia. They also lose some of the stem cells that turn into microglia. This pattern suggests that changes to microglia are secondary to other symptoms but worsen the disorder’s course.

In cultures, the microglia from these cells give hyperactive immune responses to mild stimuli, such as a lack of oxygen.

This is fascinating, says Kipnis, because people with Rett syndrome suffer from apnea. Apnea might inflame microglia, which in turn would damage neurons.

This suggests that the microglia worsen symptoms after they begin rather than causing them, says Kipnis. “Neurons are the core, there’s no question about it. But macrophages are the accelerators of the disease.”

For more reports from the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Correction: This article has been modified from the original to clarify that people with Rett syndrome experience general apnea, but rarely during sleep.

Recommended reading

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Profiles of neurodevelopmental conditions; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

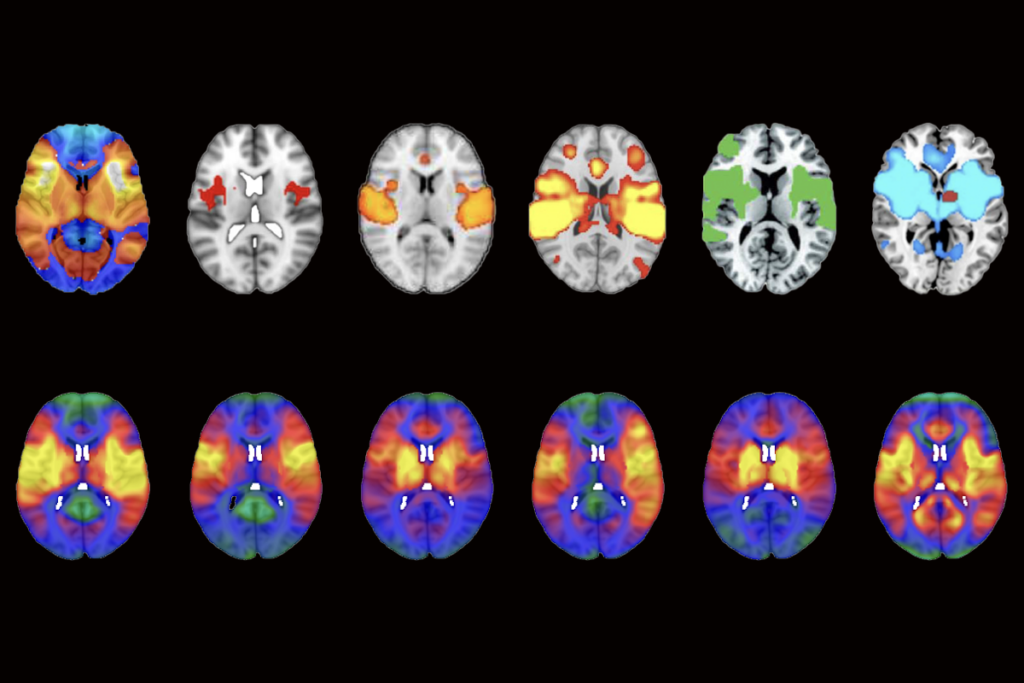

How artificial agents can help us understand social recognition

Methodological flaw may upend network mapping tool