Imaging tool maps regions within amygdala

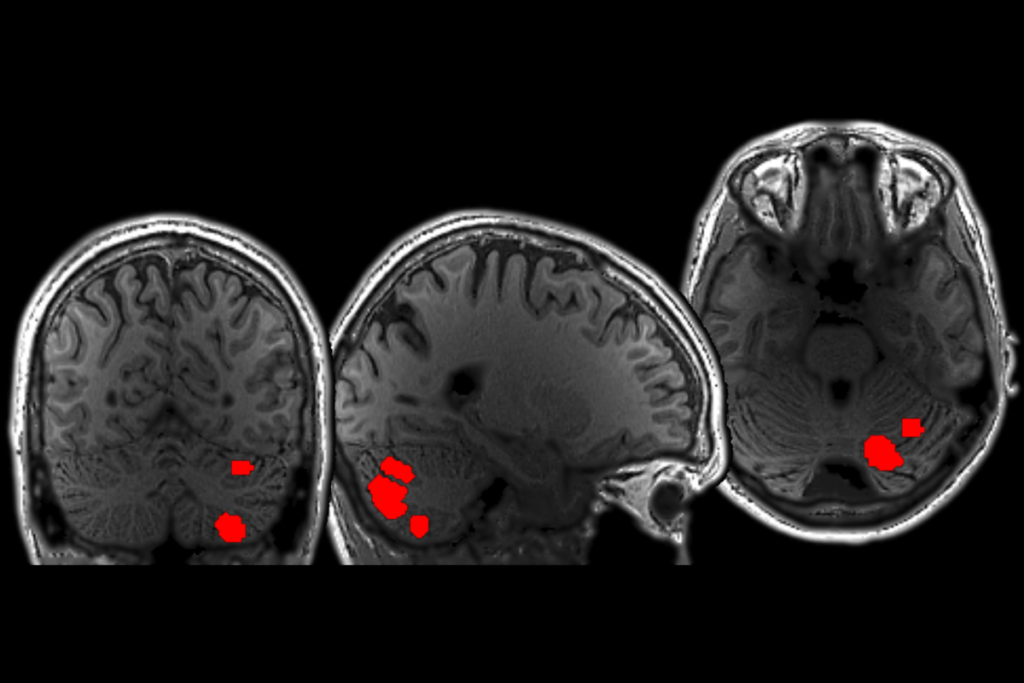

A new method can distinguish between sub-regions of the amygdala, the deep nub of tissue that is involved in emotion processing and that shows abnormal activity in people with autism, according to a study published in the June issue of NeuroImage.

A new method can distinguish between sub-regions of the amygdala, the deep nub of tissue that is involved in emotion processing and that shows abnormal activity in people with autism, according to a study published in the June issue of NeuroImage1.

Although the amygdala is often referred to as a single almond-shaped entity, it is made up of many distinct islands, which are usually divided into four areas: lateral, basal and accessory basal, medial and cortical, and central.

These sub-regions are wired differently to various parts of the brain and have distinct functions. Rodent studies have shown, for example, that the lateral amygdala is involved in fear learning, whereas the medial amygdala has been linked to processing pheromones, chemicals that affect the social behavior of many animals, including humans.

The technique could help autism researchers pinpoint parts of the amygdala that are most relevant to the disorder. Mouse models of fragile X syndrome show weak signaling of glutamate in the lateral amygdala, for example, whereas mouse models of Rett syndrome have abnormal expression of hormonal genes in the central amygdala.

Researchers have had difficulty zooming in on these discrete areas in people, however. The regions can’t easily be distinguished from one another using standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which measures changes in blood flow.

The new technique, dubbed TractSeg, delineates the sub-regions by looking instead at how they’re connected to the rest of the brain. Many studies have found abnormal connectivity in people with autism.

The researchers rely on diffusion-weighted imaging, in which a brain scanner traces the flow of water molecules in the brain. White matter — the tracts that connect nerve cells — is covered in sheaths of fat and water molecules.

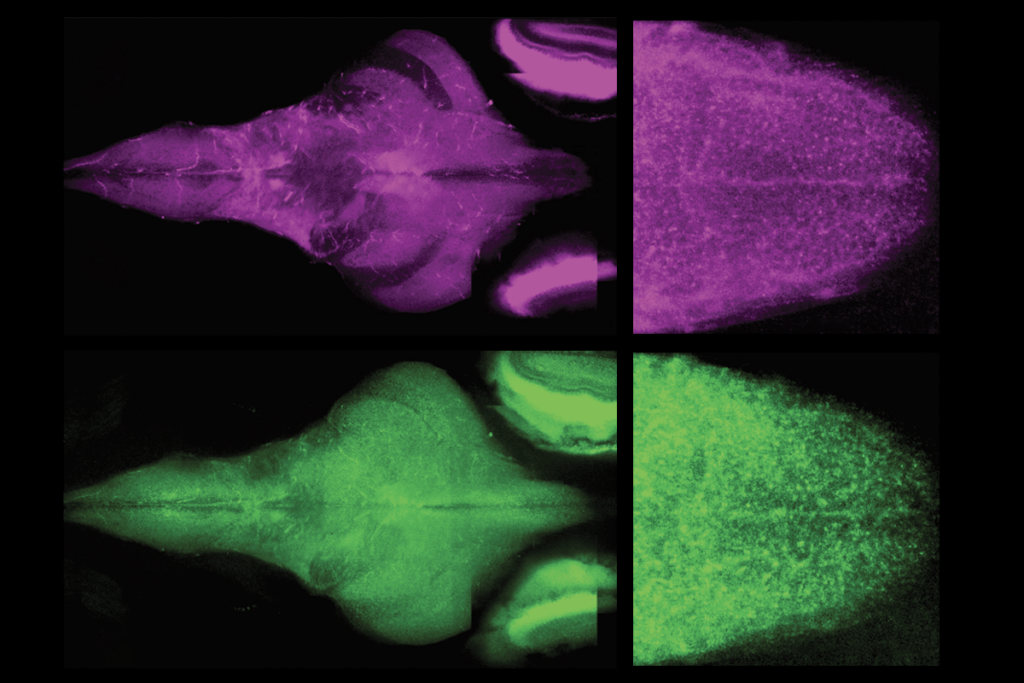

The method estimates the boundaries of the four sub-regions by comparing a participant’s amygdala connectivity patterns to those observed in animal studies.

The researchers found that in 35 healthy individuals, amygdala regions defined by TractSeg are similar in size, shape and location.

To validate the method, the team compared the boundaries defined by TractSeg with those made by a two-hour, high-resolution scan using traditional MRI. In the same participant, the two methods drew outlines that are 66 to 95 percent identical, depending on the region.

References:

-

Saygin Z.M. et al. Neuroimage 56, 1353-1361 (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

Cerebellum responds to language like cortical areas

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles