How scientists secure the data driving autism research

Protecting the privacy of autistic people and their families faces new challenges in the era of big data.

T

he cardboard box has been sitting in Maya’s house in Ohio for months. The box, no bigger than a hardcover novel, contains six plastic tubes — one for Maya, one for her husband, Mark, and one for each of their four children, two of whom have autism. It also holds labels with each person’s name, date of birth and a barcode printed on them, ready to be affixed to the tubes once the family has filled them with spit. (Maya requested that only her first name be used in this article, to protect her privacy.)The box came from SPARK, the largest genetic study of autism to date. To participate, Maya will have to ship the family’s samples back to a DNA testing lab in Wisconsin. But she keeps wavering.

On the one hand, Maya applauds SPARK’s mission to speed autism research by collecting genetic data from more than 50,000 families affected by the condition. (SPARK is funded by the Simons Foundation, Spectrum’s parent organization.) She hopes the effort might lead to better means of early diagnosis and treatment. Mark did not know until college that he has autism; by contrast, their children, diagnosed at 23 and 32 months, benefitted from early therapy.

But Maya also worries about giving her family’s DNA and health information to a third party. When she was in graduate school, she was initially denied a job after a prospective employer found an article about her having Marfan syndrome, a genetic condition that affects connective tissue.

The SPARK data are stripped of identifiers, such as a person’s name and birth date. And with rare exceptions, none of the DNA data are shared without a participant’s consent. But Maya questions how well those protections work. Could unauthorized individuals get access to the data and find a way to identify her and her family? Could that affect her children’s future? Most autism research databases allow participants to later withdraw their data. But if those data have already been used in a study, they generally cannot be extracted because doing so could change the study’s results, experts say.

“I want to be really sure that the data will be anonymous,” Maya says. “I don’t want my decisions now to affect my child’s employability 10, 20 years from now.”

Maya is not alone in her unease. Many families who are enthusiastic about participating in autism research also fear that their personal health information could leak out online or get into the wrong hands, exposing them to stigma or discrimination. Their concern is not entirely unjustified: Privacy laws in the United States do nothing to stop a small employer or life-insurance company from discriminating against someone based on their genetic information. And even when data are anonymized, scientists have shown how hackers can match names to genomes and brain scans stored in databases.

But sharing data with a research institution is less risky than sharing them with healthcare providers or with many commercial genetic-testing companies, experts say. Research databases have more safeguards in place, such as data encryption and restricting data access to trusted researchers — measures that have largely dissuaded hackers so far. “Researchers are definitely the best and direct-to-consumer companies in general are definitely the worst, because there are dozens of these companies, and many either don’t have a privacy policy or don’t follow it,” says Mark Rothstein, director of the Institute for Bioethics, Health Policy and Law at the University of Louisville in Kentucky.

No matter where DNA or brain-imaging data go, they are never completely secure — sticking people like Maya with a difficult decision. For now, most participants should feel reassured. “If the scientific databases are properly protected, the risk of data theft is relatively low,” says Jean-Pierre Hubaux, who heads the data-security laboratory at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland. But researchers need to stay ahead of that curve if they want to preserve their study participants’ trust.

Identity crisis:

A

utism research increasingly relies on big data, and as more studies share data, some privacy concerns only become more pressing. Larger databases potentially make for bigger targets, especially in combination with digital information that is publicly available.The MSSNG project, run jointly by four groups, including the advocacy group Autism Speaks and Verily (formerly Google Life Sciences), has sequenced more than 10,000 whole genomes of autistic people and their family members. The National Database for Autism Research at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) stores information about more than 100,000 autistic people and their relatives, including sequences of their exomes (protein-coding regions of the genome), brain scans and behavioral profiles. The Simons Simplex Collection contains whole genomes from 2,600 trios, or families with one autistic child. And as of late 2019, SPARK — the study Maya may participate in — had exome sequences and genotyping data for more than 27,000 participants, 5,279 of them with autism. The study also has health, trait and behavioral data for more than 150,000 people, 59,000 of them on the spectrum.

Other servers house collections of brain scans. The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE), for example, pairs brain scans with clinical data from more than 1,000 autistic people and a similar number of controls. From 2012 to 2018, a project called EU-AIMS collected brain scans and whole-genome sequences from 450 people with autism and 300 ‘baby sibs’ — younger siblings of people with autism, who have elevated odds of being diagnosed with the condition themselves.

All participants in these research projects sign documents that outline how their data will be collected, de-identified and shared. This ‘informed consent’ process is supposed to let them weigh privacy and other risks before they sign up, and it is required by law in the U.S. and most other places. But these documents can be difficult to parse. “Even if you’re very well educated, [the language] is still probably not as clear as it could be,” says Kevin Pelphrey, a neuroscientist and autism researcher at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Informed-consent documents also don’t provide the complete picture. For example, most studies specify that the data will be stripped of identifying information such as names, birth dates and cities of birth. Studies routinely replace those facts with alphanumeric codes, such as global unique identifiers. The codes provide an anonymous way to track individuals across studies, but they don’t make data secure. In fact, as the amount of digital data for each person grows, it becomes easier for outsiders to piece together a person’s identity and health background from different sources.

Someone who has access to a person’s genome from one source can readily determine if that genome is present in another database, researchers showed in 2008. The team used genetic markers called single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as benchmarks. They compared how often thousands of SNPs appear in a person’s genome with how often those same SNPs appear in both the database and in a population with similar ancestry. If the frequencies in the person’s genome are closer to those in the database than to those in the reference population, the person’s genome is likely to be in the database. If the database centers on a particular condition, the identified individual would be associated with that condition.

Even without access to a participant’s genome, it may be possible to identify the person. Another team of researchers used a computer program that extracts sequences of repeating genetic markers from anonymous genomic data to create genetic profiles of the Y chromosome of 50 men whose genomes were sequenced in the 1000 Genomes Project, a study of human genetic variation. The same profiles exist in a public genealogy database, linking them to family names. The team put the names together with each man’s age, hometown and family tree — as listed on the 1000 Genomes website — to identify them in public records.

Repositories of brain scans have similar vulnerabilities. Facial-recognition software, for example, can be used to match publicly available photos of people with features that incidentally show up in some brain scans, one 2019 study shows.

Countless other strategies that don’t call for high-level hacking skills can pin names and other information to genetic and health data. “Any person who has some background on genomics or has some background about statistics can do these types of things,” says Erman Ayday, a security and privacy researcher at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

Security breaches aside, health data can leak out in less sinister ways: Millions of times each year, people sign authorization forms that give employers and insurance providers permission to access their health records when they apply for certain jobs, such as a police officer, or when they request life insurance, workers’ compensation or Social Security disability benefits.

And more than 30 million people have sent their DNA to genetic-testing companies such as 23andMe. That company, along with six similar companies, has agreed to follow voluntary guidelines for protecting privacy, including promising not to share genetic data with employers or insurance companies without permission. But a 2018 survey of 55 similar testing companies in the U.S. revealed that many lack basic privacy protections or do not explain them; 40 companies did not state in their documentation who owns the genetic material or data, and only a third adequately described the security measures used to protect those data.

Patchwork protections:

S

o far, major research databases have escaped the attention of rogue actors, experts say. “There are not really instances where malevolent forces have hacked these research databases and caused any real harm,” says Benjamin Berkman, a bioethicist at the NIH in Bethesda, Maryland. But that may be, in part, because healthcare providers with lackluster security are more tempting targets. Health providers account for more than 36 percent of all publicly known security breaches — the most of any single type of organization — according to an analysis of more than 9,000 data breaches from 2005 to 2018.After the first high-profile demonstrations of de-identifying data showed up, the NIH and some research institutions tightened privacy protections — removing SNP frequencies from websites the public can access, for example, or removing some identifying information, such as ages, from the 1000 Genomes site. But in 2018, as it became evident that virtually no data breaches were actually taking place, the NIH loosened its rules again, providing public access to the genomic data it had taken off public sites a decade earlier. (Researchers leading genetic studies of specific groups can still request that the NIH limit public access.)

“Sometimes the science changes and we, meaning the people who are in charge of protecting the public, we overreact,” says Thomas Lehner, a scientific director at the New York Genome Center who used to coordinate genomics research at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Brain-scan data may also be less vulnerable than last year’s experiment suggests. Experts say that identifying members of the general public in a large database of brain scans is much harder than matching scans to a few dozen photos that were designed to be similar in luminance, size and other features, as happened in that study. Also, autism researchers can use software to remove facial features from brain images in databases — and some of these tools come bundled with image analysis programs. “It’s easy to just remove the face — nobody will ever reconstruct who’s who,” says Martin Styner, a computer scientist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Many universities actively protect DNA and brain-scan data by restricting access to them: Researchers must apply for access through a university ethics committee and explain how they intend to use the data. And many studies, such as ABIDE, have protocols for making sure the data they collect from various research groups are de-identified or ‘defaced.’ “We give them scripts for defacing,” says Michael Milham, who directs the International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative, which supports ABIDE. “Before we ever share [data], we go through and check to make sure the defacing is as it should be.”

Beyond the technical challenges, decoding identities from anonymized data also breaks federal law. “If any of my colleagues tried to do something like identify a particular person, I would expect them to lose their jobs, pay an enormous fine and probably go to jail,” Pelphrey says. In 2010, a medical researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles spent four months in prison for looking into the confidential medical records of his boss, coworkers and celebrity clients such as Tom Hanks, Drew Barrymore and Arnold Schwarzenegger. The year before, in 2009, the University of North Carolina demoted a cancer researcher for negligence and cut her salary almost in half when a breast-imaging database she oversaw was hacked, putting the personal data of 100,000 women at risk. “[The lapse] had quite strong consequences, leading to her retirement,” Styner says.

Researchers who are granted access to large autism research databases such as MSSNG also sign agreements that specify harsh penalties. “Besides legal action, Autism Speaks would revoke privileges to the researchers and institution through our controlled-access point to the database,” says Dean Hartley, Autism Speaks’ senior director of discovery and translational science.

Some U.S. federal data-privacy laws may protect people from harm if their personal data fall into the wrong hands. The U.S. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), for instance, prevents health insurance providers and large employers from discriminating against people based on a genetic predisposition to a particular condition. But the law does not apply to small businesses, to life or disability insurance providers, or to people who already have a health condition. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 provides more complete privacy protection than GINA by extending protection to people with a confirmed diagnosis and not just to those with a genetic predisposition.

Some states have passed laws to fill gaps in the federal laws and give people the right to seek redress for violations of their privacy. Still, many privacy and security experts remain concerned as more personal health data get shared across more databases. “There are a number of people who have been talking about [whether] we really need to look at GINA in the context of big data and the merging of these databases,” says Karen Maschke, a research scholar at The Hastings Center, a nonprofit bioethics research institute in Garrison, New York.

Even with stronger legal protections, law enforcement or courts can demand access to a research database. To shield the data from such requests, research institutions can obtain a ‘certificate of confidentiality’ from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This protection is not iron-clad, however. Evidence for its effectiveness relies upon a small number of legal cases, and if researchers are unaware that they have the certificate, as many are, they will not invoke it, experts say. What’s more, the certificate becomes moot when laws require the reporting of information about infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, for the sake of public health.

Saving a smile:

A

s an autism researcher and the parent of two autistic children, Pelphrey understands both sides of the privacy dilemma. Pelphrey and his autistic children have contributed their DNA through five separate studies to databases such as the National Database for Autism Research, and they remain open to future contributions. But he understands why some people hesitate to get involved. “I think a smart way for scientists to proceed is [to] think about what they would want their family doing,” Pelphrey says.As part of that, researchers have the responsibility to explain the privacy protections they put in place, and to provide examples of how a participant’s health data might be used, he says. “We will make a point of going through the consent form and saying, ‘In this section about data sharing, this could mean data is shared with other researchers, and those researchers may be collaborating with companies,’” Pelphrey says. “We won’t list your name and identifying information, but it is your data that has pictures of your brain and information about your genome.”

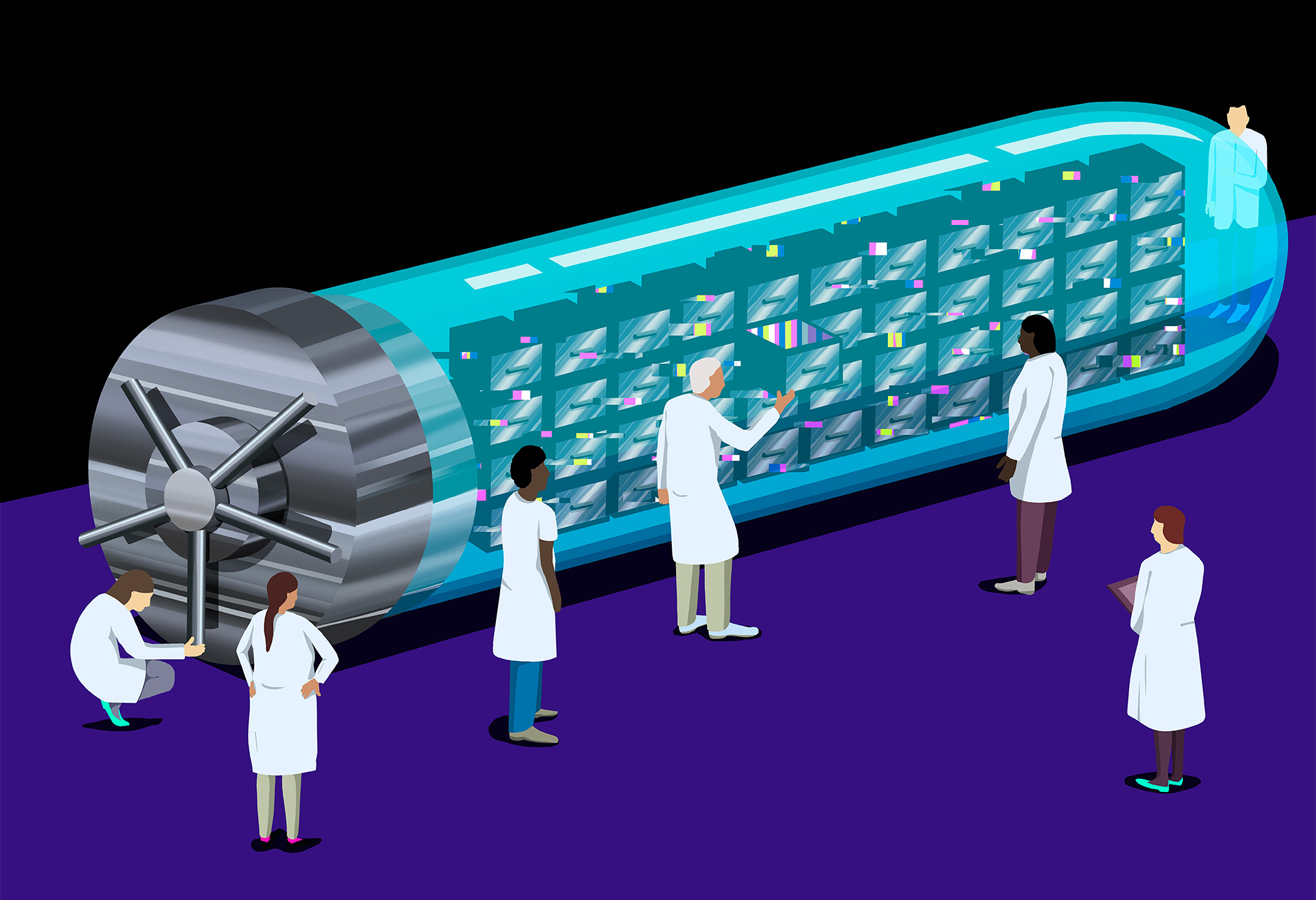

Scientific institutions typically guard the data they store with multiple layers of security. Many autism databases are stored on cloud platforms that use security chips and keys along with data-encryption tools, while also allowing vetted researchers to copy and download data onto local servers. And experts are investigating even more secure ways of storing and sharing sensitive data, says Adrian Thorogood, a legal and privacy expert at the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health. One approach involves allowing access only via the cloud, blocking researchers from copying or downloading any data. Another strategy is to use ‘data stewards’ to provide information to researchers, who would not be able to directly access the data but could submit queries or models.

Data-privacy tools are also turning up in the software applications autism researchers use. The makers of one screening app, which flags key behaviors in videos captured by smartphone cameras, are developing a privacy filter to obscure sensitive information in the videos. The filter can, for example, obscure a person’s gender or maybe even her ethnicity while still capturing facial expressions useful for analyzing behavior. “If I want to detect a smile, I could filter the image such that only points corresponding to regions of the face relevant to a smile are preserved, each such point simply represented by a moving dot,” says Guillermo Sapiro, an engineering professor at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who leads the project.

Despite such progress, participants in genetic studies still shoulder a degree of risk to their privacy. In exchange, some hope to gain knowledge about their own genetic makeup, although many large autism research projects are not designed to turn up individual results.

In 2011, Maya and her family signed up for the Genes Related to Autism Spectrum Disorders study, designed to identify genetic differences between boys and girls with autism. They had hoped that their participation in the study would enable Maya’s husband and autistic son to get the genome sequencing recommended by their son’s physician. But participants in that study could only request that the researchers contact a doctor of their choice for follow-up testing if a clinically relevant genetic variant turns up — there is no option to get results directly, says lead investigator Lauren Weiss, a human geneticist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Sometimes participants are willing to take the privacy risks involved just to help move science forward. If Maya decides to participate in SPARK, she does not expect to directly benefit, she says, but hopes that such research fuels progress in the area of early autism diagnosis. “I don’t think I expect the research we participate in to help my family — research is a long process,” Maya says. “But if we can help families who haven’t yet had an autistic child, then that’s worth it.”

Meanwhile, the box of tubes sits unopened.

Recommended reading

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Explore more from The Transmitter

Frameshift: Shari Wiseman reflects on her pivot from science to publishing

How basic neuroscience has paved the path to new drugs