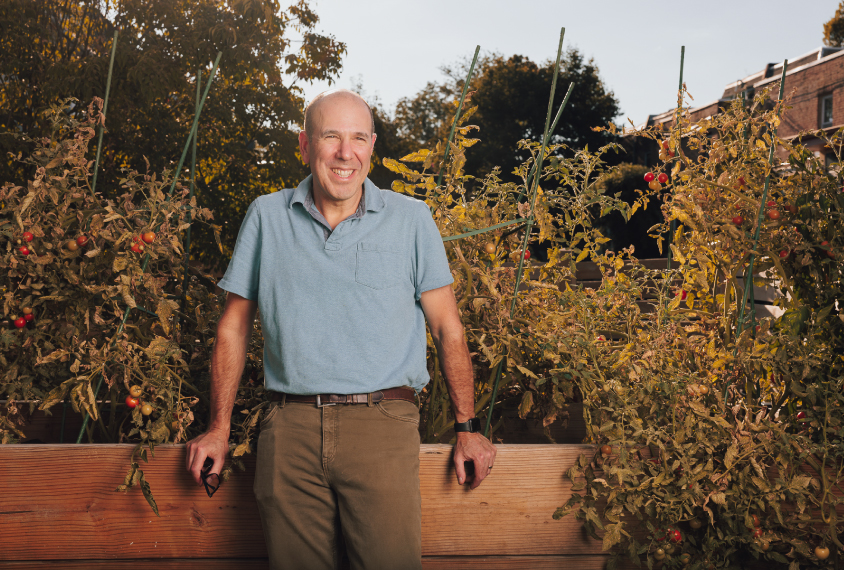

When David Mandell’s mother became sick in 1997 from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he left New York City and moved back to Baltimore, Maryland, to be close to his parents and start graduate school. He had grown up there before leaving for college in New York, so it felt like a strange homecoming.

Mandell’s parents had been a big influence on him. They had both grown up poor in New York City — his father in Brooklyn and his mother in the Bronx — and they had cultivated strong commitments to civil rights. Conversations around the dinner table in the Mandell house focused on matters such as race and fairness, his parents saying that racism in Baltimore drove disparities in housing, hiring, police interactions and more for Black Americans.

Through these conversations, Mandell had come to understand that race and class could affect the margin of error allowed in life. But he had also been influenced by their careers. His father was a clinical psychologist who researched substance misuse treatments at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and his mother was a special-education teacher who helped design programs for the mayor’s office, aimed at reducing child abuse in Baltimore.

Mandell was able to spend about 10 months in Baltimore, cooking and cleaning in the three-story brick house in which he grew up, and keeping his mother company during her treatments. When she died from an infection related to her weakened immune system, Mandell was still only in his 20s, and the grief changed something in him, showed him a different side of the world.

“We’re not trained in our society to deal with death, to deal with losses that others experience,” he says. “Losing a parent, experiencing a loss like that, removed a lot of those social barriers for me.” In the wake of her passing, he found himself more comfortable approaching people and asking them about their lives, and what he might do to help.

It is this type of research that has earned Mandell praise as a “champion for those less fortunate,” says Connie Kasari, professor of human development and psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has collaborated on studies in autism with Mandell.

N

But he himself had a challenging start. He remembers getting kicked out of kindergarten for his restlessness. “If I finished before everyone else, my teacher would tell me to sit on my hands, and I was just incapable of doing that,” he says. “I’m sure in modern times, I’d be diagnosed with ADHD.”

He ended up attending first grade at a special-education lab school run by Towson University in Maryland. His classmates — some of whom he now suspects were autistic — fascinated him, as did the teachers, who were much kinder and more supportive than those at his old school. Mandell says the school showed him the ways autistic children can struggle in a society that was not made for them.

Partially because of this insight, Mandell cultivated an interest in psychiatry at an early age. After high school, he moved to New York to major in psychology at Columbia University. When he graduated, he worked as an associate for the Children of Alcoholics Foundation, developing curricula for professionals working with families experiencing substance use disorders — a tie to the research his father had once done.

As part of moving back to Baltimore to be close to his family, he applied to Johns Hopkins University’s masters program, though once accepted, he realized he couldn’t afford the tuition. The school offered him a slot in their doctoral program instead, with funding, and he jumped at the chance.

This arrangement created “a very weird tension,” Mandell says. His mother was “in and out of the hospital,” but when she was there, he could see her room from his grad school office. Sometimes he would leave work and go eat meals with her, sharing the new things he was learning.

By then, Mandell’s girlfriend (now his wife) was living in Philadelphia, and in 1998, in the middle of his graduate program, Mandell took an internship at Community Behavioral Health, a nonprofit organization contracted by the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Disability Services. His job was to investigate children who frequently accessed mental health services, and the high cost that generated. He spent hours asking parents about their lives, and the lives of their children. “About half these families I spoke with had autistic children,” he recalls. “I didn’t know anything about autism then. I was very moved by their stories about how they were trying to cobble together services for their kids from the education system, the mental health system, and from other social services, and how hard it was, and how bad the services were.”

This was the start of Mandell’s career in autism research. He began examining the support systems around autistic children. The number of children being diagnosed with autism was increasing rapidly then, and from his work in Philadelphia, Mandell “knew that service systems were completely unprepared” to meet the rising demand. He decided to focus on systems-level issues for autistic people.

I

Investigating inequity became a consistent theme in Mandell’s career. His most prominent contribution to the field might be his work on the costs of autism. For example, in a 2014 study, he and his colleagues found that costs for a lifetime of support for each person with autism and co-occurring intellectual disability (from lost productivity to hospital bills), may reach $2.4 million in the United States, making it one of the most expensive conditions in the nation. In addition, Medicaid claim data suggested that autism therapies did little to lower these costs.

The high dollar amounts that the study revealed brought media attention to the matter. Governments often want to consider whether support for autistic people “can make them more independent, so they can go on to be employed, tax-producing citizens,” Mandell says. “But I don’t think that’s the argument we should be using.”

Mandell would prefer to use data to make decisions on what we value as a society. For example, in a 2012 study, Mandell and his colleagues discovered that, on average, families with autistic children earn 21 percent less than those with children who have a comparable health limitation and 28 percent less than children with no health limitations. Much of that lost income was driven by the impacts on the mothers in these families — mothers of autistic children earn 35 percent less, on average, than the mothers of children with a comparable health limitation and 56 percent less than the mothers of children with no health limitations. Mandell suggests the data from that study should be used to discuss the allocation of services and resources to families in need, or to question policies on workplace flexibility.

Mandell “has consistently worked to increase access to supportive interventions for traditionally marginalized, often minority populations,” Kasari says.

M

The way in which Medicaid is administered varies from state to state, and Mandell and his colleagues investigated how these variations could lead to different outcomes for autistic people. Their 2013 study analyzed the ways in which 48 state Medicaid agencies funded the most common services for autistic children: physical and occupational therapy, speech therapy, behavior modification, and social skills training. In 42 of the states, children could not access all four common services.

Brooke Ingersoll thinks this and similar studies by Mandell and his colleagues have far-reaching potential. She is professor of clinical psychology at Michigan State University in East Lansing and is collaborating on a research project with Mandell. His work on Medicaid “provided strong support for the use of Medicaid waivers to cover autism services, in terms of improving family quality of life, reducing unmet needs and reducing service disparities,” she says.

But the area of Mandell’s research that he finds hardest is his work conducted in tandem with communities to fundamentally change how autism is addressed in schools, mental health centers, primary practices and elsewhere.

It began with the first randomized trial Mandell ever conducted — a community-partnered study that focused on autism education in Philadelphia. The study occurred by accident, he recalls. In Pennsylvania, parents with children in early-intervention systems can elect to keep their children in their programs for an extra year instead of sending them to kindergarten when they are old enough. This costs the state a lot of money, so there was a political interest in getting families to move their children to kindergarten, he says, and the city’s school district wanted to investigate it.

In 2007, as Mandell and his colleagues were close to submitting their proposal for a study, the director of autism services for the school district of Philadelphia said he had a better idea. He wanted a new program in place, and he thought he had one. He asked Mandell to help him implement it, and in return Mandell would be able to analyze the results.

Mandell and his colleagues completely rewrote their proposal, changing it from an observational study to an experimental one. “We had two programs tested against each other and randomized people into getting different kinds of care,” Mandell says.

The project became the largest-ever randomized trial of an educational intervention for children with autism, and the first to be conducted as a partnership between an academic research center and a school district. “We actually initially got null results, but that was still important information that led to making things better,” Mandell says. “It was the basis of completely new ways of thinking about autism in Philadelphia.”

This is the kind of work he finds most rewarding. “The data are messy,” he says. “There’s a lot of negotiation and compromise because to do it well, and for the results to get sustained once you are done, the community partners have to have equal or greater voices than yours in decisions about the research.”

But precisely because it is done in collaboration, it “has the greatest potential to result in sustained meaningful change” of anything he’s done, he says. And it has bolstered his reputation among his peers.

“I think he is fearless,” says Catherine Lord, professor of psychiatry and education at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has served on committees with Mandell. “He takes on big questions and is willing to jump into incredibly difficult issues which need to be solved.”

M

After Mandell’s mother passed away, he threw himself more deeply into his graduate studies, but he also stayed in Baltimore to keep his father company for a while, and to share in his grief.

Although these things happened before Nuske became one of his mentees, she has indirectly benefited from that period of Mandell’s life. For instance, when Mandell is trying to discern the main issues that plague his community partners, he always asks them, “What’s keeping you up at night?” Nuske says. “That has stayed with me through the years.”

It’s the kind of question meant to get to the thrust of the problem. It’s simple and direct. The question is also open-hearted — a tactic he learned through processing his mother’s death.

“I still find myself thinking about what she would think was the right thing to do,” Mandell says. “That drives me a lot.”