How do you design a home for someone with autism?

Aspects of housing design can be a huge deal for someone with autism: Small changes can have a big impact on their quality of life.

What if every time the bathroom fan buzzed, you became unhinged? Or you lived in a place where it felt impossible to avoid curious neighbors whenever you went outside? Or where the location of kitchen appliances made it feel like a combat zone every time you tried to cook a meal?

Only then might you start to feel like the many adults with autism who struggle to live in homes that don’t accommodate their needs.

Today, although the majority of adults on the spectrum live in the home of a parent or other family member, their caretakers are now wondering what will happen when they get older and can no longer take care of themselves – let alone someone on the spectrum.

Over the past decade, investments in autism research and interventions focused on children and adolescents have grown. In 2010 alone, nearly $350 million funded research projects in the United States.

But autism is a lifelong condition, and just 2 percent of these research funds are focused on the needs of adults.

In the past, adults with autism had few options to live independently in a community. They’d often end up in developmental centers, nursing homes or intermediate care facilities. Only in recent years have families and professionals started to consider designing, developing and choosing residences in the community.

In order to respond to these specific needs, we recently wrote a book – “At Home With Autism: Designing for the Spectrum” – that provides a robust set of guidelines for architects, designers, housing providers, families and residents.

No ‘one size fits all:’

There’s a saying in the autism community: “If you know one person with autism, you know one person with autism.”

In other words, there is no single set of characteristics for those on the spectrum. Each individual has varying degrees of difficulty with social situations, verbal and nonverbal communication, and repetitive behaviors.

They could have a range of medical and physical issues – seizures, sensory sensitivities, sleep dysfunctions and gastrointestinal problems. Some excel in visual skills and pattern recognition, while others are especially adept at music, math and coding.

With all of this in mind, there’s no umbrella approach for housing those with autism. The best-case scenario would include a generous range of residential options – available within a single community – so that individuals could discover and choose which best suits them.

This, unfortunately, is not feasible, making it challenging to find a home that’s a good fit, especially when the options are so limited.

Planning for independence:

Researchers, support providers and design professionals are only now starting to explore how to plan for individuals on the spectrum once they age out of the school system, including where they will live, how they can set up a home, and the best way for them to become members of a community.

For those at the beginning stages of planning for their kids or grandchildren with autism to move out of the house, the questions and concerns are manifest: Is it better to live in an urban apartment, with the mix of services, amenities and vitality that cities provide? Or would they be better served in a gated community developed specifically for individuals on the spectrum?

What about roommates? Are there advantages to having them? If so, how many? And are there home technologies that can enhance security and independence without invading privacy?

Then there are the home’s layout, room sizes and configurations. Design aspects that most don’t think twice about can be a huge deal for someone with autism: Proper lighting, wall colors and appliance noise levels need to be considered.

For those who haven’t cooked or cleaned before, the arrangement of countertops, the sturdiness of cabinetry, even how the water flows out of the kitchen faucet can be the difference between mealtime being a frustrating or satisfying experience.

A lot of little things can add up:

Several years ago, a local autism organization asked us what was the best housing design for adults on the spectrum. We were stumped. So we began to sift through countless reports, personal accounts and emerging research studies on adults with autism that could inform us of better ways to design such residences.

We wanted to craft design guidelines for residential settings that would enhance key quality-of-life goals that are particularly important to those on the spectrum. They include sensory balance and being able to control privacy and social interaction, in addition to having choice and independence, clarity and predictability, and access and support in the neighborhood (to name a few).

With these goals in mind, we developed key criteria to assess the suitability of a home, outdoor space and community, and what design modifications might be needed to maximize its livability.

The guidelines encompass everything from big-picture suggestions at the level of the neighborhood to specific tips for individual rooms; they range from the community’s social life to the durability of household fixtures.

For example, to make it easier for individuals to assimilate into the community, when adding exterior features such as fencing, it’s important to make sure the materials and forms fit in with the rest of the houses in the neighborhood, and aren’t fortress-like or institutional-looking. In the yard, raised garden beds provide good opportunities for sensory-seeking people with autism to touch and smell plants.

Inside the home, predictability can be a big deal to some on the spectrum. Each room should have an obvious purpose, transitions between rooms should be smooth and their boundaries should be clear. This may help a person with autism establish routines and increase independence, while minimizing anxiety.

There’s also a wide range of technologies that can mitigate stress and promote independence. Installing an exit/entry system with a camera and intercom/telephone allows the resident to preview visitors before opening the door. Meanwhile, activity monitors and task prompting systems can help people on the spectrum feel like they have greater control over their lives and more independence.

For those with sensory sensitivities, air conditioning and heating systems should be as quiet as possible. Ideally, they’ll be situated away from bedrooms to minimize disruption.

In the bedroom, closets with built-in organization systems and good lighting can help with daily dressing and grooming tasks; and in the bathroom, toilets should have heavy-duty seats and bowls to accommodate wear that could come from repetitive movements like bouncing.

Because requirements, needs and tastes of those on the spectrum vary widely, it’s necessary to work closely with residents. The importance of doing this cannot be overemphasized: A well-designed environment that addresses the needs and aspirations of individual residents might not only improve their quality of life and ability to live independently, it could also minimize long-term costs associated with relocating residents when homes aren’t a good fit.

Sherry Ahrentzen is Shimberg Professor of Housing Studies at the University of Florida. Kim Steele is a Ph.D. candidate in urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. It has been slightly modified to reflect Spectrum‘s style.

Recommended reading

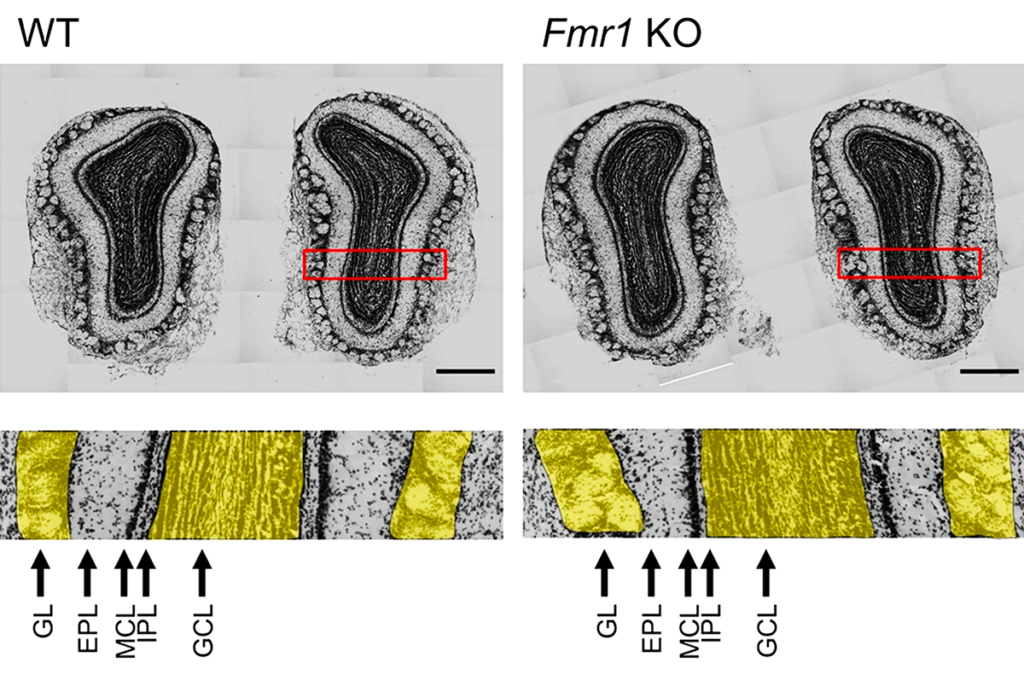

Olfaction; autism-linked genes in monkeys; eye movements

Roundup: The false association between vaccines and autism

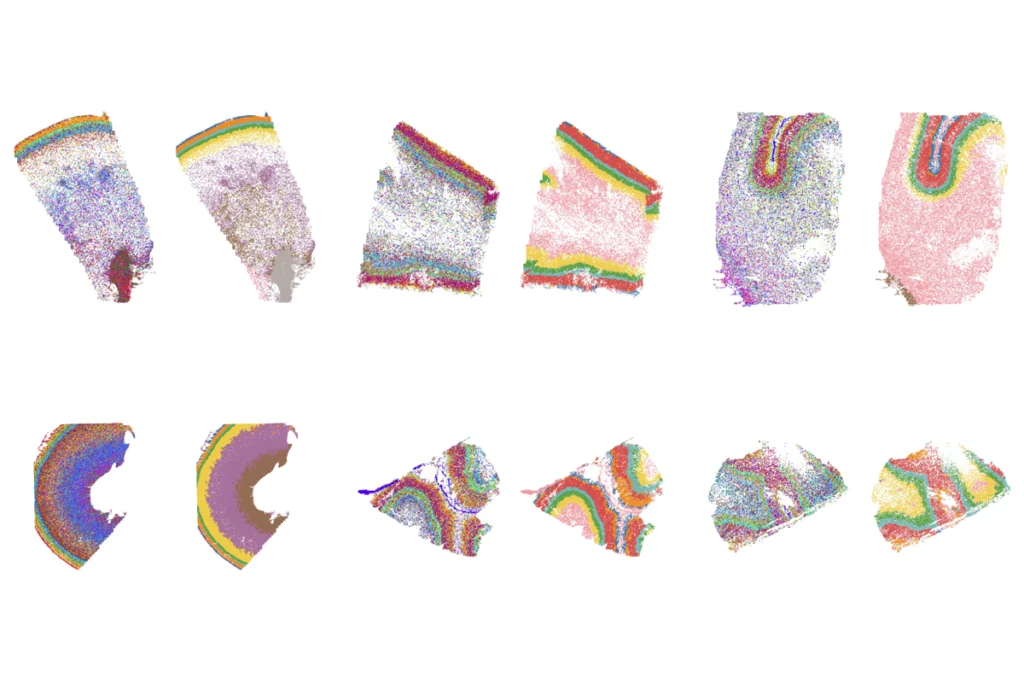

New human brain atlas charts gene activity and chromosome accessibility, from embryo to adolescence

Explore more from The Transmitter

Plaque levels differ in popular Alzheimer’s mouse model depending on which parent’s variants are passed down