How a controversial condition called PANDAS is gaining ground on autism

Some scientists say an immune condition called PANDAS affects as many as 1 in 200 children who have traits similar to those of autism. But many experts contest that figure — and even the condition’s very existence.

A

dam Elliott was 2 years old when his parents began to suspect he might have autism. Adam had trouble making eye contact — one telltale sign of the condition — and there were other hints as well. He was a calm, inquisitive child most of the time, but some days at preschool, he would become unfocused and uncoordinated, fumbling with scissors as he tried to cut paper for art projects.By the time Adam entered elementary school, his traits had worsened. He began to experience severe separation anxiety and sensory overload in the noisy classroom. He became aggressive. When he was 6, for example, he believed his best friend was saying nasty things about him and scratched the friend in the face with a pencil. At home, Adam would often walk in circles, filled with anxiety. He eventually became so afraid that his food was poisoned, he refused to eat for long periods of time.

Adam’s parents took him to a dozen different specialists during this time, including occupational therapists and psychologists. None were willing to attach a label to Adam’s condition, recalls his mother, Wendy Elliott. One doctor diagnosed Adam with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and prescribed amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (Adderall), but it did little to quell the boy’s obsessive thoughts and behaviors.

By 2015, when Adam was 8, Elliott began to fear she might have to have him hospitalized. She took him for a full psychological evaluation with Rebecca Daily, an autism specialist at the University of Oklahoma. During the visit, Elliott mentioned that Adam’s problems had all started when he was a toddler, around the time he had had his tonsils and adenoids removed. Doctors had recommended the surgery because he had had so many bouts of strep throat.

“What did you say?” Daily asked.

Elliott repeated what she had said.

She remembers Daily then saying: “This is not autism, this is not ADHD. This is a disease called PANDAS.”

Elliott had never heard of PANDAS, short for ‘pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections.’ But the diagnosis had been gaining traction over the previous two decades. In 1998, Susan Swedo, then a pediatrician at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), first proposed PANDAS to explain an apparent association between strep throat, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and tic disorders such as Tourette syndrome. By Swedo’s estimate, the condition affects up to 1 in 200 children, but many experts contest that figure — and even the condition’s very existence.

Pediatric neurologists point out that Tourette syndrome and OCD are highly heritable; if strep plays a role in these conditions at all, it is extraordinarily rare. Strep, by contrast, is common. In one study that followed 814 children for 12 weeks, for example, about half of the children had ongoing strep infections, and they did not show more obsessive-compulsive behaviors or tics than the other children.

Still, PANDAS has attracted a vocal band of proponents who have proposed it as a catchall for a wide range of mental health issues sometimes lumped under the broader term ‘autoimmune encephalopathy.’ The list of purported triggers has grown from strep to include Lyme disease, mononucleosis and herpes. And the range of possible outcomes has expanded to encompass ADHD, anorexia nervosa and autism. The boundaries between these diagnoses can be subjective, and some clinicians and parents are quick to attribute obsessive-compulsive behavior to PANDAS, even when it may stem from autism, OCD or something else. “There’s going to be diagnostic confusion whether a child has a late presentation of autism or if they have PANDAS,” Swedo says.

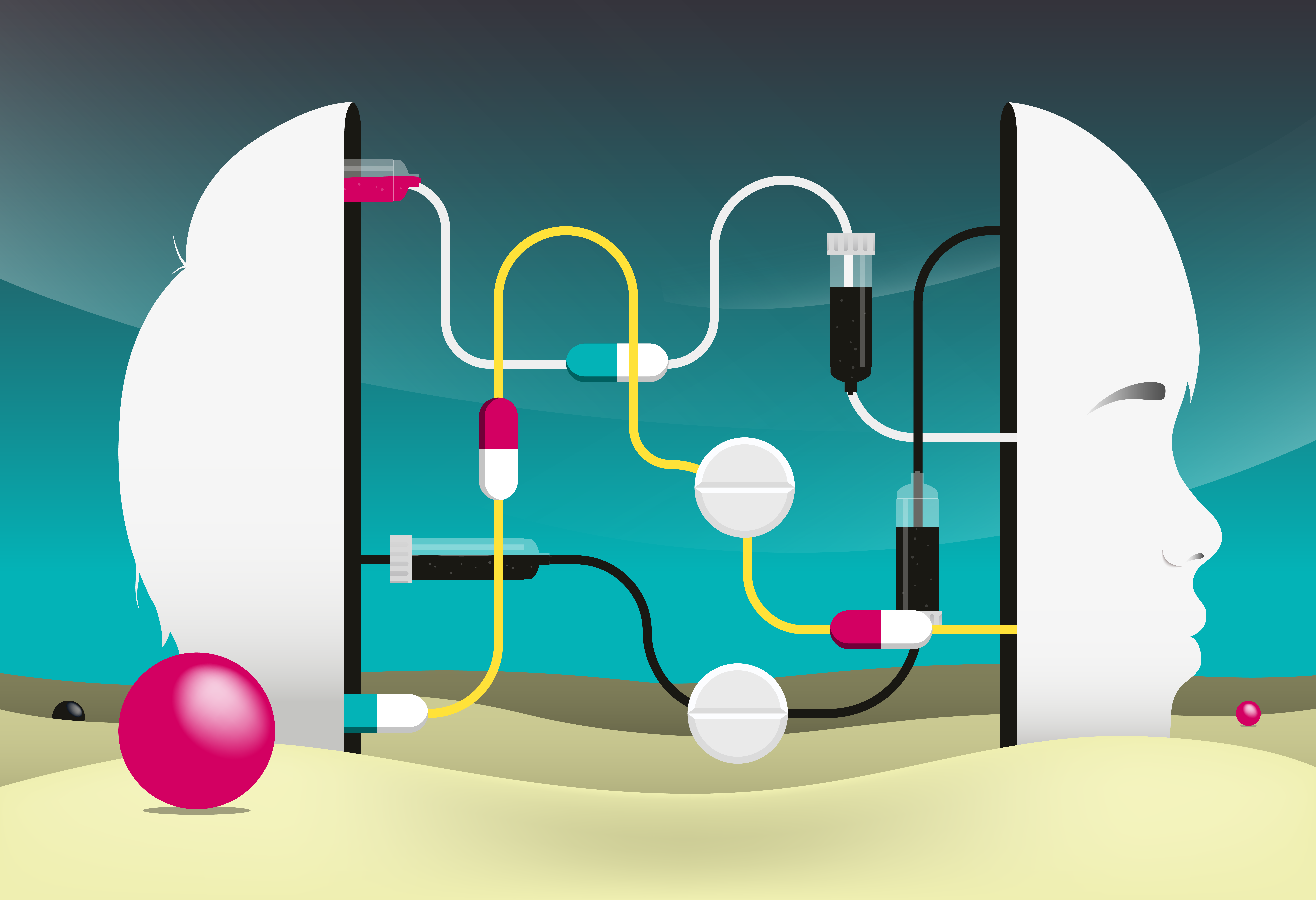

Daily recommended that Adam take a test developed by a colleague of hers, microbiologist Madeleine Cunningham. Oklahoma-based Moleculera Labs, which Cunningham co-founded, markets the $925 test — called the ‘Cunningham Panel’ — for children who are not responding to treatments for psychiatric conditions and who may instead have “a treatable autoimmune disorder.” One brochure reads: “Could an infection be causing your child’s symptoms?”

Whether they pursue the test or not, parents who suspect their child has PANDAS often end up seeking expensive, unproven and potentially dangerous treatments — including, in rare cases, rituximab, an immunosuppressant typically used for cancer treatment and organ transplants that has serious, sometimes deadly, side effects. Medical quacks and profiteers have thrived, largely unchecked in a marketplace that intersects with the outer fringes of the autism and chronic Lyme communities. One Oklahoma company, for instance, markets donkey milk as a PANDAS treatment. Most parents end up paying out of pocket, but five states have passed laws mandating insurance coverage for treatment of the condition.

The condition’s rising popularity notwithstanding, several experts say the way it is being diagnosed and treated is worrisome. “Allow me to be considered a naysayer,” says Edward Kaplan, an expert in streptococcal infections at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. He says there may be a neurological trigger for the behavioral changes in some children diagnosed with PANDAS, but the link to strep is tenuous at best. “This disease is diagnosed by all kinds of people more frequently than perhaps it should be.”

Brain invaders:

P

ANDAS emerged in the late 1980s in the wake of a resurgence of rheumatic fever in Pennsylvania, Utah and Missouri. Rheumatic fever is an immune response to group A streptococcus, the bacterial strain that causes strep throat and scarlet fever. It arises when those infections are not treated properly, usually in children. In the worst cases, it can lead to heart failure or permanent heart damage. Some people need to take antibiotics for a decade or more.Up to 30 percent of children with rheumatic fever develop distinctive motor and behavioral traits called Sydenham chorea or, less commonly these days, Saint Vitus’ dance, after the patron saint of neurological conditions. Children with this condition exhibit jerky, involuntary movements of their hands, feet and face. By some accounts, they also become irritable and prone to emotional outbursts, have trouble concentrating and temporarily lose their ability to read and write. “A frequent complaint heard from the mother is that the character of her child is completely changed,” wrote Canadian physician William Osler, who first characterized Sydenham chorea in 1894.

During the rheumatic fever outbreak, Swedo sent questionnaires to 37 parents, asking them about their children’s behaviors. She says she hoped to find a brain-based explanation for OCD, which had, until then, largely been credited to harsh parenting techniques. The findings confirmed her suspicions: Children with Sydenham chorea had significantly more obsessive thoughts or behaviors than children with rheumatic fever alone. Based on follow-up interviews, Swedo determined that three children diagnosed with Sydenham chorea met the diagnostic criteria for OCD.

Swedo then inverted her approach. Rather than seeking out children with rheumatic fever, she began studying children with OCD and Tourette syndrome, and swabbing their throats for evidence of a strep infection. She often found it — which is not surprising because it is a common infection, and many children also carry the bacteria without getting sick. What was surprising, Swedo says, was what happened when she started treating those children.

She recalls one child who refused to swallow his spit, preferring, instead, to stockpile it. “He had three cups under his bed,” she says. When she treated him with penicillin, she says, “he responded beautifully; his obsessive-compulsive symptoms disappeared.” He then had another strep infection, and the OCD-like behavior “came roaring back.” In another child, she tried ‘plasmapheresis,’ a technique to separate the child’s blood cells from the plasma and strip out the germ-fighting antibodies circulating in his system. She says that led to an 80 percent decrease in the boy’s OCD traits, according to his parents.

Based on those observations and more over the next decade, Swedo came to believe that an immune response to infection can trigger an improperly diagnosed class of psychiatric conditions. She would go on to investigate and rule out other connections between infection and conditions of brain development, including the spurious association between Lyme infection and autism. In 2006, she proposed a trial to test ‘chelation therapy,’ which some parents of autistic children pursue based on the bogus belief that mercury and other heavy metals in vaccines cause the condition. Critics called the trial unethical and a waste of funding, and it was ultimately abandoned due to safety concerns.

It was PANDAS that would become Swedo’s legacy. In 1998, Swedo proposed five criteria to diagnose PANDAS: the presence of OCD or a tic disorder, sudden onset prior to puberty, a waxing and waning pattern of trait severity, an association between strep infections and behavioral traits, and neurological abnormalities such as jerking movements or problems with coordination. Despite the clear, testable criteria she laid out, the definition of PANDAS proved elastic in the hands of practitioners. By 2008, one study had found that only 39 percent of children diagnosed with PANDAS actually fit Swedo’s original definition. So many children were diagnosed, in fact, that Stanford University’s multidisciplinary PANDAS clinic — the first of its kind when it opened in 2012 — sees children from within only a seven-county area and only if they agree to participate in research.

Given the surge of interest, the NIH launched a $3 million multicenter study — the largest and most rigorous analysis of the condition. The researchers followed 71 children who met PANDAS diagnostic criteria over two years and compared them with children who had traits of Tourette syndrome or OCD but not PANDAS. Two landmark studies, published in 2008 and 2011, found that in 91 percent of all PANDAS cases, there was no association between the timing of strep infections or presence of strep antibodies and flare-ups of OCD or tics. Even though children with PANDAS were more likely to receive antibiotics than the other children were, the researchers could detect no difference in the number of flare-ups the children experienced.

The NIH makes no mention of these studies on its information pages about PANDAS, which Swedo helped draft. To be fair, the results left just enough room for doubts to creep in. Many strep infections go unnoticed and can trigger immune reactions that standard tests do not detect. The researchers consulted Swedo before the trial, but she says they approached it with an agenda to disprove PANDAS. For example, she says, most of the PANDAS children in the study had Tourette syndrome over a long period of time and showed no signs of abrupt-onset OCD, PANDAS’ hallmark behavioral trait. However, Kaplan, an investigator on those trials, says all of the participants fit Swedo’s published definition.

Swedo and her colleagues later proposed a new, broader condition that would better fit the state of the evidence: pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, or PANS. This umbrella diagnosis is not restricted to children with strep or any other type of infection. It might even be caused, for instance, by environmental factors or metabolic disorders. Nor is it limited to young children: PANS can strike anyone up to the age of 18. The main requirement for PANS is the acute onset of OCD or restricted food intake, though the working guidelines make it clear that “mild, non-impairing obsessions or compulsions” do not “rule out the syndrome.”

One 2015 study in mice revealed how strep infections could cause brain inflammation, but no studies have followed a large group of children to try to link infections and PANDAS since the NIH-funded studies. Asked why no one has attempted a new study, Swedo says the field has moved on, adding, “You can’t fight a felonious report with additional data.”

Magic markers:

A

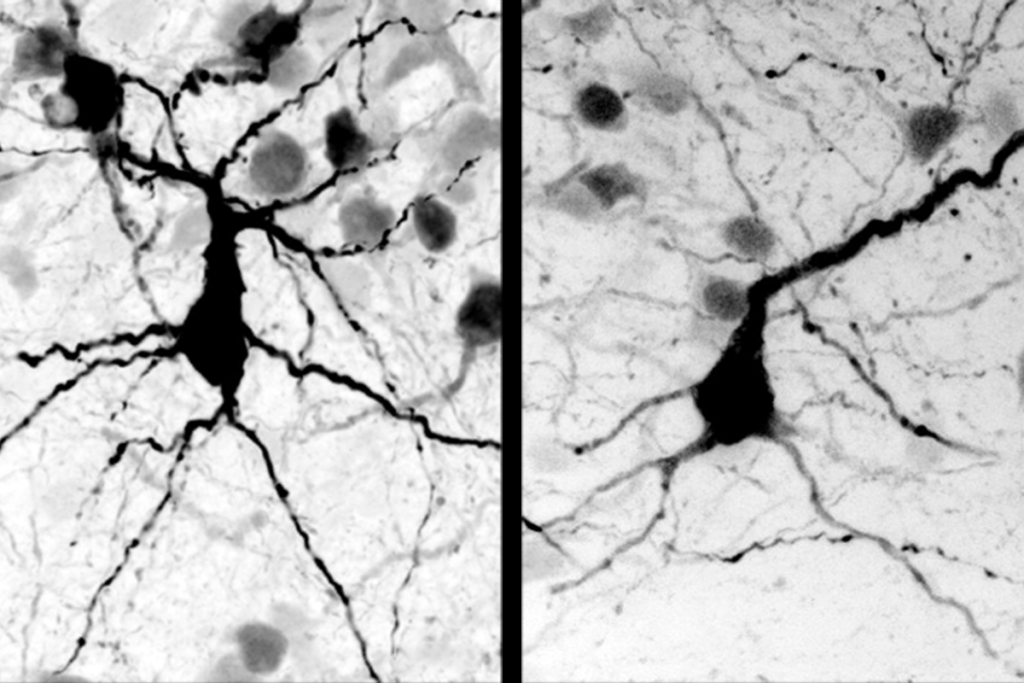

s the goalposts for a PANDAS diagnosis started to shift, some experts saw a need to pin them down. Cunningham began to hunt for markers of the condition — measurable, molecular signs that would identify a child with PANDAS or PANS.Cunningham is known for her work on rheumatic fever, in which the immune system mistakes muscle proteins in the heart for strep, leading to cardiac complications. In 2003, her lab found that a similar process might be at work in Sydenham chorea. Working with Swedo and other colleagues, she showed how strep antibodies produced by the immune system can latch onto receptors in the nervous system and attack the brain. The team found a way to measure four of these antibodies, plus an enzyme that seems to shift into overdrive during this kind of immune attack.

Cunningham tested whether these five molecules might serve as diagnostic markers for PANDAS and concluded that they did. But in 2008, independent studies at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, raised doubts about the utility of Cunningham’s biological markers and the link between infection and PANDAS flare-ups.

That did not keep Cunningham’s team from the patent office: In 2011, Cunningham and Craig Shimasaki, a molecular biologist and entrepreneur, founded Moleculera Labs to commercialize the test Cunningham had developed. Their website says that a single elevated enzyme “may indicate a clinically significant autoimmune condition.” This claim clashes with published results showing similar levels of the enzyme in people with and without PANDAS. Moleculera has reported that autistic children may also receive a positive result, raising further questions about the utility of the test.

In one 2017 study, the Cunningham Panel did not distinguish 20 people with psychiatric conditions who met the formal criteria for PANDAS or PANS from 33 who did not. Susanne Bejerot, professor of psychiatry at Örebro University in Sweden, who led the study, was so disturbed by the findings that she recruited 21 controls — including a fellow doctor with no history of mental illness — to take the test. She found that 86 percent tested positive for at least one of the five markers on the Cunningham Panel. “Parents are very happy about the Cunningham Panel because they always get positive results,” Bejerot says. “That means they can show it to a clinician and get antibiotics or other treatments.”

Shimasaki has challenged Bejerot’s results, arguing that Bejerot’s team did not properly screen the controls for psychiatric disorders and that the type of blood-collection tubes they used interfere with the assay. Bejerot says she used the tubes specified by Sweden-based Wieslab, which marketed the test in Europe at the time. Weislab stopped offering the test several months after the publication of Bejerot’s results. This year, Shimasaki and his colleagues reviewed Cunningham Panels from 58 children who had taken the test more than once and found that a decrease in the levels of any of the biomarkers tracked with fewer or less severe traits.

In Adam Elliot’s case, two of the five markers on the Cunningham panel were above normal levels. His physician prescribed the antibiotic azithromycin, which Adam took three times a day for about two years. Long-term use of azithromycin and other antibiotics can lead to the development of antibiotic resistance and even hearing loss. Adam is now a “happy, healthy kid,” his mother says, and only takes antibiotics if he experiences neurological issues. She admits that there are “days that PANDAS rears its ugly head” and he gets on the “OCD hamster wheel.” She sometimes still wonders if he has autism but says, “The Cunningham Panel gave me the peace of mind that we’re not on a wild-goose chase.”

Skeptical inquirer:

I

n 2017, Swedo and her colleagues published what they called “consensus guidelines” for the treatment of PANS and PANDAS, which include behavioral interventions, short- and long-term courses of antibiotics, steroids, immunoglobulin therapy, plasma exchange and even injections of the cancer drug rituximab. A systematic review a year later offered only weak support for their recommendations.Swedo says the recommendations are based on clinical experiences with thousands of people with PANDAS. Rituximab, she says, should only be considered in life-threatening cases. Others, however, are unequivocal in their concern. Rituximab should not be used for PANS outside of a clinical trial, says Donald Gilbert, a pediatric neurologist at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital in Ohio: “This is a very powerful medication, and somebody is going to get hurt.”

Gilbert studied philosophy before he became a doctor. He gives lectures on PANDAS that sound more like epistemology than medicine, as he explores the role of inference and the nature of causality. “I’m a skeptic by nature,” he says.

In August 2018, Gilbert gave a talk for primary care physicians with the relatively staid title “PANDAS and PANS: A clinician’s guide to management.” In it, he challenged the anecdotal evidence PANDAS supporters frequently cite. He also recommended that, unless OCD traits make it impossible for a child to attend school, clinicians should not run any tests, offer any treatments or provide any neurology referrals. In his slides, he wrote: “Inoculate the family with education so they do not seek out a PANDAS/PANS clinic.”

After the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital posted a video of the talk online, the PANDAS Network, a nonprofit advocacy organization that is listed as one of the National Institute of Mental Health’s Outreach Partners, shared it on Facebook. All hell broke loose. “Move over you foolish man,” read a comment from the PANDAS Network’s account. “Step away from the podium.”

“His swipes at Dr. Swedo and Cunningham … are so incredibly rude and flat-out unprofessional,” one commenter wrote.

“This man needs to be stopped,” wrote another.

Within a week, the group had issued a “call to action,” directing its members to file complaints against Gilbert with the Ohio State Medical Board and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. “[Dr. Gilbert] mocked the disorder, disparaged researchers, misled attendees, encouraged physicians to commit medical malpractice, and generally enjoyed a jolly good time laughing along with his colleagues at desperate parents,” attorney Beth Maloney wrote in a letter to his employer. “The general medical bigotry that was on full display caused me to wonder whether your hospital will next try to take PANDAS children from parents who disagree with its doctors.”

Gilbert says he was upset by the attacks but chose to ignore them at first. When he attended a professional conference a few months later, however, the organizers left his name off the program and advised him to register at the hotel under a false name for his own safety. While he was there, he says, Swedo, who retired from the NIH last year and now serves as chief science officer for the PANDAS Physicians Network, asked to meet him.

When they met in the conference hotel, Swedo handed him printouts of his slides along with her handwritten responses. Gilbert disagreed with her about the science but says he saw that she wanted him to recognize the rigor in her own work. Swedo says she remains deeply offended that Gilbert compared her to a quack. “I had grounds to sue him, but I chose not to,” she says. She says she tries to warn parents about snake-oil salesmen and shuns healthcare providers she believes are over-diagnosing PANDAS. She lays blame for the explosion in questionable fringe therapies on the PANDAS naysayers such as Gilbert. “The controversy is responsible for the overtreatment of these kids,” Swedo says. “Mainstream medicine has failed to deliver recognition of suffering and a promise that we are going to find out what is happening.”

Mind meld:

I

n early October, more than 200 parents gathered inside a hotel ballroom in Arlington, Virginia, for the annual meeting of the PANDAS Network. In this crowd, there was little doubt about the link between brain inflammation and OCD, Tourette syndrome and autism.A poster on an easel out front advertised a children’s book, “In a Pickle Over PANDAS,” featuring a cuddly panda on the cover. Attendees all received pamphlets touting the Cunningham Panel. And over the course of the day, a steady stream of talks focused on the condition and its consequences: Researchers lectured on the basic biology of strep, PANDAS parents offered advice to their peers, and clinicians endorsed a variety of therapies rarely covered by insurance.

“You guys are desperate, everybody knows that,” said Elizabeth Latimer, a popular PANDAS doctor in Washington, D.C., who does not accept insurance. She was there to help, she said. She shared her theory, which multiple studies refute — that PANDAS is becoming an epidemic because tonsil removal has declined. She also told parents she believed that a disproportionate number of people diagnosed with autism actually have PANDAS instead. “I’ve treated children who have been diagnosed with autism who no longer have autism,” she said.

The final talk of the day came from Shimasaki, Moleculera’s co-founder and chief executive officer. He gave his own rundown of the history of PANDAS and described several case studies, in which children’s Cunningham Panel results improved following various therapies. He explained that in his view, the purported inflammatory processes at play in PANDAS might explain an array of neurological conditions, including schizophrenia, seizure disorders and autism.

“With vision and with perseverance, PANDAS, PANS, all these other autoimmune encephalopathies I believe will one day just be treated as common and caught early,” he said to the crowd. “Our mission is to help change how medicine is practiced for neuropsychiatric disorders, but as Winston Churchill said, ‘Never, never … never give up.’” In fact, Churchill never said those words, but the parents in the audience seemed inspired by the sentiment. The room filled with applause.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025