The healthcare system is failing autistic adults

Adults on the spectrum frequently have a range of other conditions — but they rarely get the help they need.

R

ebekah Hunter lay in the hospital bed, terrified. A nurse had taken Hunter’s underwear earlier in the emergency room and warned that an alarm would sound if they got out of bed. (Hunter, who presents as female, identifies as non-binary and uses the pronouns ‘they’ and ‘them.’) If Hunter had to use the bathroom or wanted to walk around the room, they needed to ask the nurse’s permission.Hunter, then 28, was already on edge. They had tried to overdose on ibuprofen and acetaminophen and were being held in the hospital under observation. Anyone would find the experience distressing, but Hunter’s distress was magnified by the fact that they are autistic.

Like many people on the spectrum, Hunter suffers from bouts of depression and chronic gastrointestinal problems. At the time, Hunter was also in an abusive relationship. (Some research suggests that abusive relationships are common among people on the spectrum.)

Hunter had been seeing a therapist but says the sessions weren’t helping. “I felt like a lot of the stuff I was going through was dismissed,” Hunter, now 30, recalls. “I would tell her that I felt like my partner didn’t care about me, that I didn’t feel safe; she’d talk me down and say it was fixable. It felt like gaslighting.”

The experience was one of many that left Hunter feeling that no one in the medical community was willing to listen to them. And so it was with the nurses in the hospital, too. Scared of angering them, Hunter shut down completely and complied with everything they said. Hunter felt helpless; they couldn’t sleep because the lights were on all the time and the hospital gown was itchy. It took about four days of this “sensory torture” before they were released.

Like Hunter, many autistic adults struggle to receive good care from doctors and hospitals. These individuals often find it difficult to communicate with healthcare professionals and are misunderstood or ignored. They’re less likely to have their routine health needs met, from dental check-ups to tetanus vaccinations. “I think that as an autistic person, I’ve had to habituate to other people’s rules and comfort levels,” Hunter says.

For their part, primary care doctors and mental health providers are often unprepared to treat this population. Many are unaware that adults on the spectrum are at risk for a range of other ailments in addition to their autism: Adults with autism are almost twice as likely as their typical counterparts to have diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease, for instance. As a result, they die, on average, 16 years earlier than typical adults matched for gender, age and country of residence, according to one study. Making sure people on the spectrum receive routine and preventive care could help bridge that mortality gap.

“A lot of adults with autism feel lost,” says Lisa Croen, director of the Autism Research Program at Kaiser Permanente, a managed healthcare provider based in California. “It’d be great if physicians had some more general training and awareness. Just like with any other condition, they really have to take into account that particular person in their office and adjust what they’re doing to meet the needs of that patient.”

Croen and others are working on a number of potential solutions — including specialty clinics, online tool kits and training programs for community mental health workers. And some autistic adults, including Hunter, are eager to offer their input.

”“A lot of adults with autism feel lost. It’d be great if physicians had some more general training and awareness.” Lisa Croen

Growing pains:

M

ore than half of all adults with autism have additional diagnoses. Apart from diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease, they also tend to have obesity, autoimmune diseases, hearing impairment, sleep disorders and gastrointestinal problems — plus a laundry list of psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.Some of these conditions, such as constipation and sleep problems, are also common in autistic children, says Croen, which may be a consequence of the autism or reflect some common physiologic or genetic ground. But others, including heart disease, more often arise in adulthood.

Still, autism is often erroneously described as a childhood condition, and children are where the vast bulk of research dollars and media attention are focused. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1 in 59 children has autism, up from 1 in 150 in 2002. “These kids have been growing up and reaching their adulthood and now need medical care just like anybody,” Croen says. But all evidence suggests that’s not happening. One study last year, for example, analyzed the insurance records of more than 16,000 people with autism, aged 16 to 23, and found that outside of emergency-room visits, their use of healthcare services dropped significantly with age.

“This is a huge issue; we see adults who still go to their pediatrician because there just aren’t enough providers for general care or psychiatrists who will see adults with autism,” says Julie Lounds Taylor, a developmental psychologist at the Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Lounds Taylor studies the transition of autistic teenagers to adulthood. “The challenge is: Can you find someone who will take you, and can you find someone who will provide competent care?”

Andee Joyce, a former medical transcriptionist in Hillsboro, Oregon, says she has faced numerous barriers in trying to navigate the healthcare system as an adult. She was diagnosed with autism in 2007 at age 44. Thanks to her work, she knows all the diagnostic jargon. Even so, nearly everything about doctors’ appointments has been a challenge, starting with scheduling them, she says. Because telephone conversations often become garbled for her, she always procrastinates. “I only have so many spoons for phone calls,” she says. (Some people with a disability or chronic illness refer to the ‘spoon theory’ to explain the limited energy they have available for daily tasks.)

Once she has an appointment — to see her therapist about her depression, her endocrinologist about her polycystic ovary syndrome or her primary care physician about sinus issues — arriving on time can be a trial. She has learned to write down in advance everything she wants to discuss with her doctor because, she says, “my mind and my mouth aren’t always in sync.” And she wants details — all of them. In May, for instance, when her doctor prescribed a nasal spray for ongoing sinus issues, she wanted to know exactly why, when and how she should use it, along with any side effects. “I tell doctors, ‘Err on the side of over-explaining,’” she says. Her doctor didn’t mention the spray’s terrible aftertaste, which startled and distressed her.

Joyce finds dental appointments to be the “absolute worst,” between her sensitive gag reflex and the discomfort of having her mouth “stretched open like the Grand Canyon.” Some women on the spectrum find gynecologic visits the most intimidating. Autistic women are significantly less likely to visit a gynecologist and get pap smears, which screen for cervical cancer, than other women of the same age. The gap may be due to a combination of factors: Primary care doctors may assume these women aren’t sexually active, for instance, or the women may avoid visits because they are hypersensitive to touch.

Few clinics cater to these special needs. The Women with Disabilities Gynecology Clinic at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor is one of the few that treat women on the spectrum. Unlike a typical women’s clinic, it has an array of charts, pictures and anatomically correct dolls, along with tiny speculums, so that the staff can tailor their explanations to their clients, including those with intellectual disability. Women who visit the office are also encouraged to bring advocates with them to help ensure they’re as comfortable as possible and receive all the information they require.

For the physicians at the clinic, flexibility is key, says Susan D. Ernst, the gynecologist who directs the clinic. Ernst regularly takes histories while women pace around the exam room; she doesn’t force them to sit. She says one woman she sees communicates through a voice output device and requests that Ernst dim the lights so that the exam is less overwhelming. Many women need two or more visits to get through a full exam. It all comes down to accommodating the individual’s needs, Ernst says. “These patients really shouldn’t have to be seen in a special clinic,” she says. “What we really need to do is educate providers so that any physician is able to care for them.”

The doctor will see you now:

After Hunter was released from the hospital, they decided it was time to find better care. “I just left and found a new doctor,” Hunter says. That might sound straightforward, but as it is for Joyce, making appointments can be difficult for Hunter. “Phones are scary to me,” Hunter says. “It’s a deterrent.”

Over the next two years, Hunter was prescribed an array of antidepressants by various doctors. Hunter also developed gynecological problems in the form of irregular bleeding and says their doctor largely ignored their questions and didn’t take notes during appointments. “At first I thought it was that he was hard of hearing; I speak softly,” Hunter says. “But it became a horrible nightmare.”

Hunter’s doctor’s approach is the antithesis of what Ernst and others have found to be effective when treating people on the spectrum. At the Neurobehavior HOME program at the University of Utah, for example, the entire clinic is designed around people who have disabilities. The center is funded entirely by Medicaid and provides medical and mental health care to about 1,200 people with developmental disabilities, 60 percent of whom are autistic adults.

Providers slot a full hour for each appointment, which allows for late arrivals and helps keep the waiting room quiet and uncrowded (crowded spaces are tough for people with sensory sensitivities). Exam rooms are large, allowing people to move around as needed and to bring caregivers along. There’s a phlebotomy lab on site, with staff trained to help ease anxiety during a blood draw. And a nutritionist works with clients to manage weight gain, a common side effect of seizure and antipsychotic medications that can contribute to other conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease.

“Being able to very closely integrate our care is huge, and we’re showing it’s leading to much better outcomes for adults with autism,” says Kyle Jones, who directs the primary care team. Although autistic adults have elevated rates of conditions such as diabetes, the clinic has better-than-average rates of controlling those comorbidities and fewer hospitalizations, Jones says.

Most people on the spectrum join the program as they’re transitioning into adulthood and leaving their pediatrician, the structure and routine of school, and other familiar services. “We can help with their needs, with some of those unknowns,” Jones says. For example, in late May, a young woman with autism who was new to the program came in with her father. The father told Jones his daughter had been unable to have a dental exam because he couldn’t find anyone to sedate her; even if he had, he would have had to pay out of pocket. Jones reassured him that the program pays for dental anesthesia through discretionary funds it receives for each client from the state. “The dad started crying,” Jones recalls. “He said, ‘This has been such a huge frustration.’”

The vast majority of adults with autism don’t have access to anything like the HOME program, however. Other states either haven’t considered or have not been willing to fund similar clinics that provide ongoing care.

In Philadelphia, researchers are working to train community mental health providers to fill some of that unmet need. Last year, clinical psychologist Brenna Maddox and her colleagues interviewed adults with autism and surveyed therapists and case managers who connect them with community-based social services. She is now designing a training program, which she expects to roll out to clinics next year. One driver for the work, she says, is the fact that there is a dearth of psychiatrists and therapists who treat autistic adults — and those who do often don’t take insurance. “Of course, we could bring adults here to Penn, and I could treat them as part of a research study,” says Maddox, a postdoctoral fellow working with David Mandell’s team at the University of Pennsylvania. “But if we can train the clinicians in the community, they’re going to have a much broader and more impactful reach.”

”“This is a huge issue; we see adults who still go to their pediatrician because there just aren’t enough providers for general care or psychiatrists who will see adults with autism.” Julie Lounds Taylor

Better tools:

For now, most clinicians feel ill-equipped to treat autistic adults. That was the message Croen received when she surveyed hundreds of primary care and mental health providers in 2015. “They told us that they need more resources and training to work with adults with autism,” she says.

The study Maddox conducted received similar responses. “Treating depression and anxiety is their bread and butter — they do that all the time,” she says. “But the second it’s an adult with autism who has depression and anxiety, they don’t feel like they have the comfort level or confidence to work with them.”

Awareness is at least growing among the next generation of doctors. Ernst says dental and medical students at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor are collaborating with a local advertising firm to create and distribute a list of providers who are good at working with people who have disabilities. (Ernst is on a national list compiled by the nonprofit organization Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network.) What’s more, she and her colleagues are developing a curriculum for the medical school on caring for people with disabilities, including autism. Educating providers early in their careers, these scientists say, will make treating autistic people less daunting and help them more fully address the needs of people on the spectrum.

Until medical schools incorporate information about autism into their curricula, doctors and autistic adults have another resource to help them communicate and build better relationships. In 2016, scientists developed an online healthcare tool kit that offers a multitude of resources, from medical, legal and ethical information to worksheets that can help autistic people manage appointments. The tool kit is accessible through the Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE), a research collaboration between several organizations.

The centerpiece of the tool kit is an ‘accommodations report’ that an autistic adult or her caregiver can fill out and give to a doctor to inform treatments. “Because everybody on the spectrum is going to be different and have different needs, it’s really hard for me to tell a provider, ‘These are the things you have to do to take care of adults on the spectrum,’” says Christina Nicolaidis, an internist who leads the project. “[The accommodations report] provides really concrete, actionable items that providers would need to know,” she says — items such as an autistic person needing to have dimmed lights during an exam or to know how many test tubes of blood the clinician might draw.

Nicolaidis and her colleagues tested the tool kit in 170 adults with autism and 41 primary care doctors in 2016. The participants reported that communication with their doctor improved one month after they received the tool kit. The next step, Nicolaidis says, is to see if the tools can be incorporated into primary care practices, as opposed to something individuals take to their physician. To find out, she’s collaborating with three large healthcare networks, two in Oregon and one in California. (Croen, at California’s Kaiser Permanente, is a collaborator.) In January, they launched the two-year study, which includes around 220 people at 12 clinics, about half of which will use the tool kit.

The tool kit incorporates data from interviews with dozens of autistic adults; another six actively helped to create it. Those pages include an extraordinary level of detail. “That comes from our autistic partners saying: ‘Wait, wait, wait. Don’t just tell me I should make an appointment; I need a script to follow,’” Nicolaidis says. Her team also worked with doctors to streamline the accommodations report so that they could actually use it. “When we first started doing cognitive interviewing with the doctors, it was a disaster: ‘This is too long’; ‘I can’t look at this’; ‘It’s too much information’; ‘You need to make it shorter.’” she recalls them telling her.

The tool kit isn’t meant to be a substitute for specialized expertise. “I’ve been focused on autism for years, and I’m still not going to get it all right when I work with an autistic patient,” Nicolaidis says. “But it’s a first step to give people a way to try to make those interactions more effective, to help non-autism healthcare providers know enough about autism to be able to do their jobs.”

Hunter has learned to self-advocate without the benefit of such a resource. Their new gastroenterologist finally diagnosed Hunter with irritable bowel syndrome and has been patient and communicative about finding a treatment. “He listens to me, takes his time with me, remembers my history,” Hunter says. “I get the sense that he cares about me.” Hunter has also started seeing a primary care physician who not only listens, but also actively encourages them to explain their needs — something many of the providers Hunter encountered did not support. “It’s so much better,” Hunter says.

And Hunter is learning to advocate for others these days, too. While taking an abnormal psychology course last year, Hunter met a member of the AASPIRE team. Hunter jumped at the chance to pitch in and began reviewing and coding write-ups that struck close to home: descriptions of people’s negative healthcare experiences. In May, Hunter took on a bigger role with AASPIRE, becoming a community council member, offering feedback and creating resources to help others. In that capacity, Hunter will interact with adults on the spectrum and ensure that these individuals’ input is incorporated into programs and resources the group develops.

Hunter is in a much better place today than five years ago and eager to put their own negative experiences to use to help others: “I think we’re the only ones that know what our lives are like.”

Syndication

This article was republished in The Independent.

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

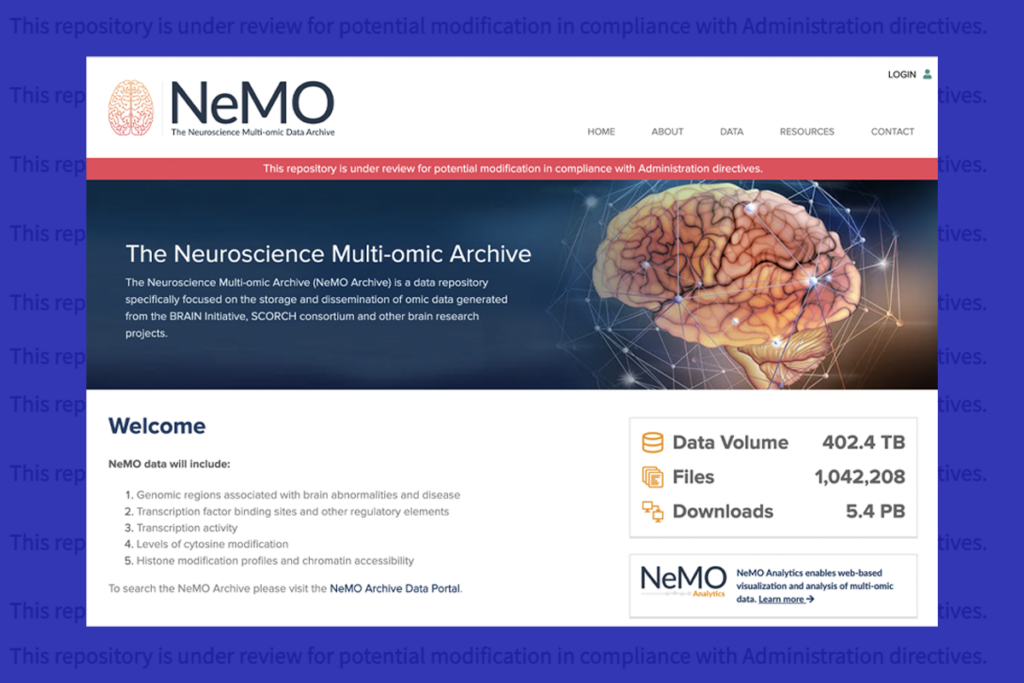

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors