Test case

A single case study suggests that deep brain stimulation may improve symptoms associated with autism, say Casey Halpern and Gregory Heuer.

Researchers have for the first time reported treating a child with autism using deep brain stimulation (DBS), an invasive procedure in which an implanted electrode delivers electrical pulses to the brain.

Researchers at the University of Cologne in Germany decided to try this aggressive treatment in a 13-year-old boy with severe autism and self-injurious behavior, and described their work in the January issue of Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. They reported that several types of drug treatments had failed to help the boy or had worked only for a short time.

DBS is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat multiple neurological disorders, including Parkinson’s disease. As neurosurgeons who perform DBS procedures, we can testify that it has a low rate of complications, and can be titrated, adjusted and reversed, making it a safe therapeutic option to be studied in a clinical trial. Indeed, we think the authors’ findings from this case report should lead to the initiation of such a trial, given how difficult autism is to treat.

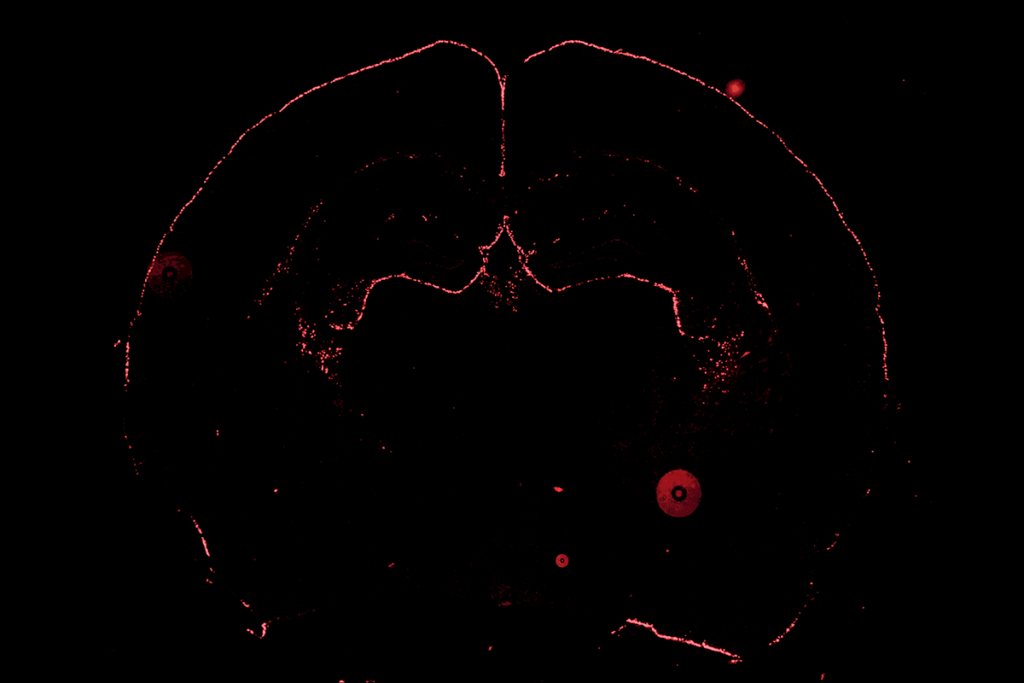

The target for brain stimulation varies depending on the disorder. In this case study, the researchers targeted the amygdala, a brain region that helps regulate fear and emotion. Research in both people with autism and animal models of the disorder suggest a role for the amygdala in some of the behaviors associated with autism.

According to the results, stimulating a part of the amygdala called the basolateral nucleus improved both the self-injurious behaviors and others symptoms of this child’s autism. Targeting other regions of the amygdala had no effect.

Researchers have used DBS to help treat self-injurious behavior in people with Tourette’s syndrome and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder, but not in people with autism. Scientists are starting to learn exactly how the treatment works: A study published 24 February in Nature revealed that DBS normalizes activity between two brain regions in people with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Given that this is a single case study, it’s difficult to draw substantial conclusions about the potential role of DBS in autism. But the findings are provocative, in large part because self-injurious behavior is particularly difficult to treat. In this case, the boy had a long history of trying to hurt himself and had to be almost constantly restrained.

Testing this type of invasive therapy in children raises obvious ethical concerns. But the researchers were motivated to attempt this off-label application of DBS because of the severity of the symptoms. And given its reversibility and the ability to adjust its dosage, DBS lends itself nicely to being used as an experimental therapy.

Neurosurgical treatment in the pediatric population needs to be approached carefully, of course, but DBS may be particularly suited to use in the developing brain.

For example, the treatment can be adjusted throughout a child’s life. DBS causes little tissue damage, so other types of direct neuromodulatory therapies would be potentially effective in the future.

Significant disability in children with autism during school-age years, particularly as a result of social isolation, markedly hinders social and educational development. Neuromodulation with DBS offers the possibility of substantial relief during a critical, transitional time in a child’s life.

Given the relative safety of the procedure and the lack of existing treatments, we think clinical trials should be considered to investigate the role of DBS in treating severely symptomatic autism.

Casey Halpern is chief neurosurgery resident at the University of Pennsylvania. Gregory Heuer is assistant professor of neurosurgery at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Recommended reading

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Molecular changes after MECP2 loss may drive Rett syndrome traits

Explore more from The Transmitter

Who funds your basic neuroscience research? Help The Transmitter compile a list of funding sources

The future of neuroscience research at U.S. minority-serving institutions is in danger