Immigrant risk

In Ireland, children born to women who have emigrated from certain African countries are more likely to be diagnosed with autism, and to have more severe symptoms of the disorder, than their peers, says Louise Gallagher.

Environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders may well represent a critical component of risk and etiology for the condition. However, such factors have been difficult to identify and quantify.

My colleagues and I delved into one of these risk factors, migration. In a report published 2 October in the European Journal of Pediatrics, we describe how, in Ireland, children born to women who have emigrated from certain African countries are more likely to be diagnosed with autism, and to have more severe symptoms of the disorder, than their peers.

Migration is a well-described risk factor for a wide range of physical and mental health conditions (such as diabetes and schizophrenia). Some studies have also reported increased rates of autism in immigrant groups — for example, among immigrants from Somalia in Sweden and second-generation Afro-Caribbean people in the U.K.

In the U.S., however, some immigrant groups, such as Mexicans, are reported to have lower levels of autism than others.

In Ireland, a defined period of immigration from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s is associated with anecdotal reports of an apparent rise in the number of children with autism born to mothers who had immigrated to the country.

We investigated this further in 366 children by conducting a retrospective review of referrals from 2007 to 2009 to a neurodevelopmental clinic in Tallaght Hospital in Dublin, Ireland. We defined immigration status on the basis of the place of birth of mothers (Irish, African and a third group, ‘other,’ composed largely of those from Eastern European and Asian countries). We looked at a number of factors, including severity of autism diagnosis, birth order, cognitive ability, age at presentation and family history of autism.

Diagnostic barriers:

Overall, all children in immigrant groups presented for diagnosis about 4.5 months later, on average, than the Irish group. This may reflect their barriers to accessing diagnostic services.

In the subset (36 percent) of children diagnosed with autism, 71 percent are Irish, 18 percent African and 11 ‘other.’ This is broadly comparable with the breakdown in the total referred population, with a range of developmental delays.

The male to female ratio in the African group is 4.27-to-1, slightly higher than the 3-to-1 ratio in the overall autism group. Children in the African group are also significantly more likely than the others (71 percent compared with 16 percent in the Irish group) to have a moderate to severe intellectual disability. They are also more likely to have more severe symptoms of autism. They tend to be third-born or later in the birth order and to have a sibling who also has autism.

Conversely, the children in the African group are less likely to have a second- or third-degree relative with an autism diagnosis, possibly reflecting the low awareness of autism in their countries of origin. We did not see these differences in the ‘other’ group.

Unpublished data from a longitudinal cohort, called Growing Up in Ireland, indicates that approximately 0.7 percent of 9-year-old children in Ireland have an autism diagnosis. This is similar to rates observed elsewhere, but prevalence data are not available for the African countries of origin (Nigeria and Congo, largely).

Birth statistics for Ireland from 2004 to 2007, when the majority of the children attending the clinic were born, indicate that 3 to 5 percent of births were to mothers from Africa, a far smaller proportion than the African group in the clinic.

It is plausible that the greater severity and familial loading in the African group reflects ascertainment bias — that is, that parents may seek health services for more severe cases, and less severe cases go undetected. We are investigating this theory using population-based data.

However, the observations fit with reports in other countries of higher rates of autism among immigrants, particularly those from Sub-Saharan Africa in Sweden and a Somali group in Minnesota.

Further investigations of this phenomenon may help to identify environmental factors or gene-environment interactions that contribute to this observation. What’s more, to fully investigate this question, we need a greater understanding of the prevalence of autism in the countries of origin.

Louise Gallagher is chair of child and adolescent psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin and heads the Autism and Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders Research Group there.

Recommended reading

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

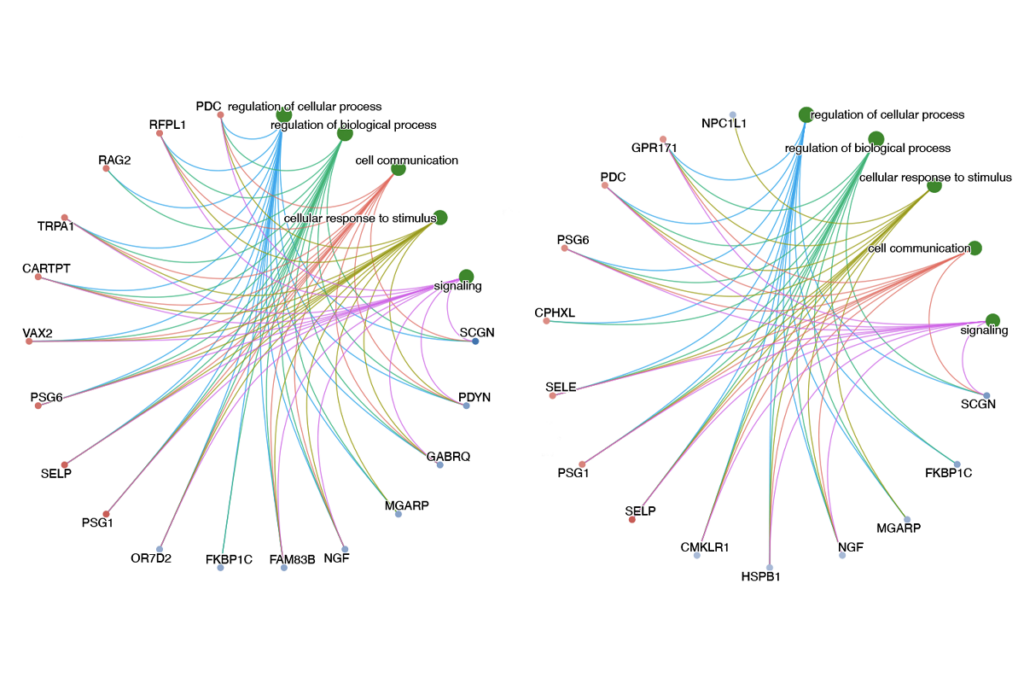

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Newly awarded NIH grants for neuroscience lag 77 percent behind previous nine-year average