Frontline diagnosis of autism

Targeted training opportunities and comprehensive guidelines can help community physicians diagnose many cases of autism, say Evdokia Anagnostou and Jessica Brian.

The first signs of autism spectrum disorder typically appear between 12 and 18 months, but the average age of diagnosis in both the U.S. and Canada is above 4 years. This delay in diagnosis presents a serious barrier to accessing early intervention, which is associated with improved outcomes for children with the disorder.

In the January issue of the Canadian Medical Association Journal, we reviewed best practices for diagnosis and presented a comprehensive set of guidelines to assist frontline physicians with early detection, diagnosis and treatment for children with autism.

Many physicians are unprepared to identify red flags for autism or make a diagnosis, resulting in long waiting lists for specialist clinics. We believe that with targeted training opportunities and the development of guidelines such as these, diagnoses can be made in the community, at least for many children with straightforward presentations. For the more complex cases, the need for specialist assessment (often via multidisciplinary teams) remains critical.

In our paper, we described four broad categories of early autism signs: social deficits, including inconsistent eye contact; language delay or related challenges, such as inappropriate use of words; limited pretend play and imitation deficits; and unusual behavior or ways of interpreting the world, such as intense visual inspection, repetitive movements and unusual sensory responses. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Canadian Pediatric Society have both proposed a variety of screening and surveillance methods.

Red flags:

By arming community physicians with increased confidence in detecting red flags, we hope to promote earlier diagnosis, either directly or via expedited referral for specialist assessment, which would open the door to more timely access to autism-specific early interventions.

What’s more, early detection of warning signs could prompt earlier referral to generic speech and language services and infant development programs, even before a diagnosis can be confirmed. These sorts of programs may be more readily available in certain communities and are often well equipped to enhance development in many domains affected by emerging autism.

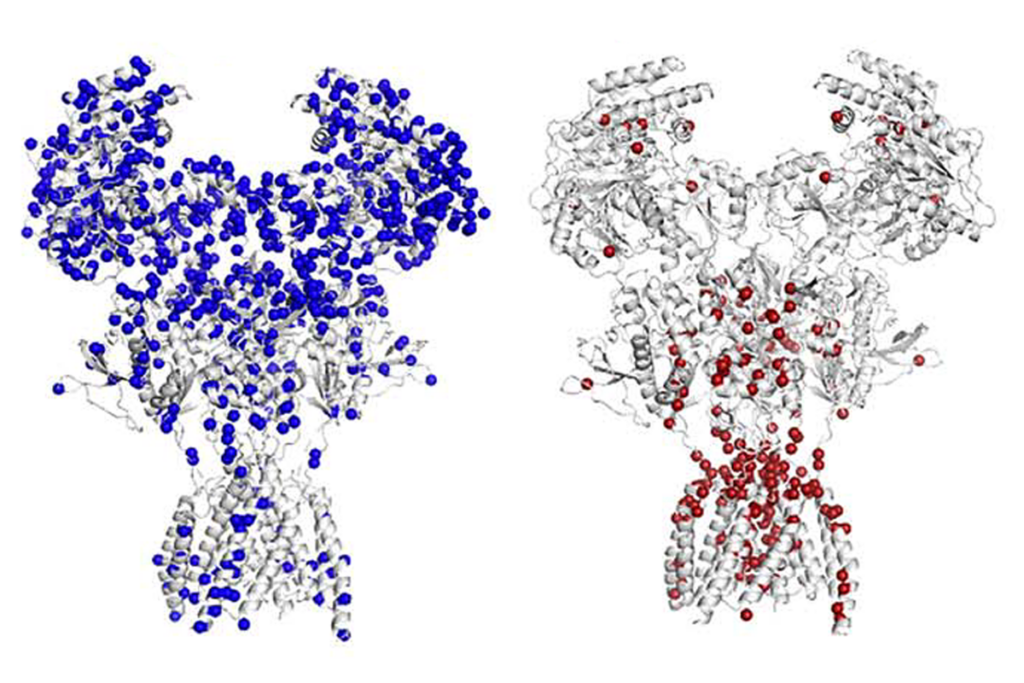

Autism is a complex and heterogeneous group of conditions that overlap with other disorders and disabilities, underscoring not only the strong role of genomics but also the emerging data to support gene-by-environment interactions.

Children with autism have a high comorbidity of sleep disturbances, gastrointestinal complaints and epilepsy. Careful history-taking and evaluation by the pediatrician are critical to not missing these common pediatric issues. In addition, common psychiatric comorbidities include attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders.

Current best practices include the use of applied behavior analysis to teach language and improve cognitive and adaptive skills in young children with autism. However, researchers are still trying to understand which models of this therapy are most effective for which specific subsets of children. The evidence for the effectiveness of treatment programs for older children, youths and adults with autism is not as strong, although benefits have been reported for a variety of structured programs.

Because early intervention is still the best-known approach to treating autism, community physicians play a key role in identifying the disorder, in referring children to specialty services when appropriate and in facilitating access to intervention as early as possible, as well as in managing care throughout the lifespan.

Evdokia Anagnostou is a clinician scientist at the University of Toronto’s Bloorview Research Institute. Jessica Brian is a clinician investigator at the institute.

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

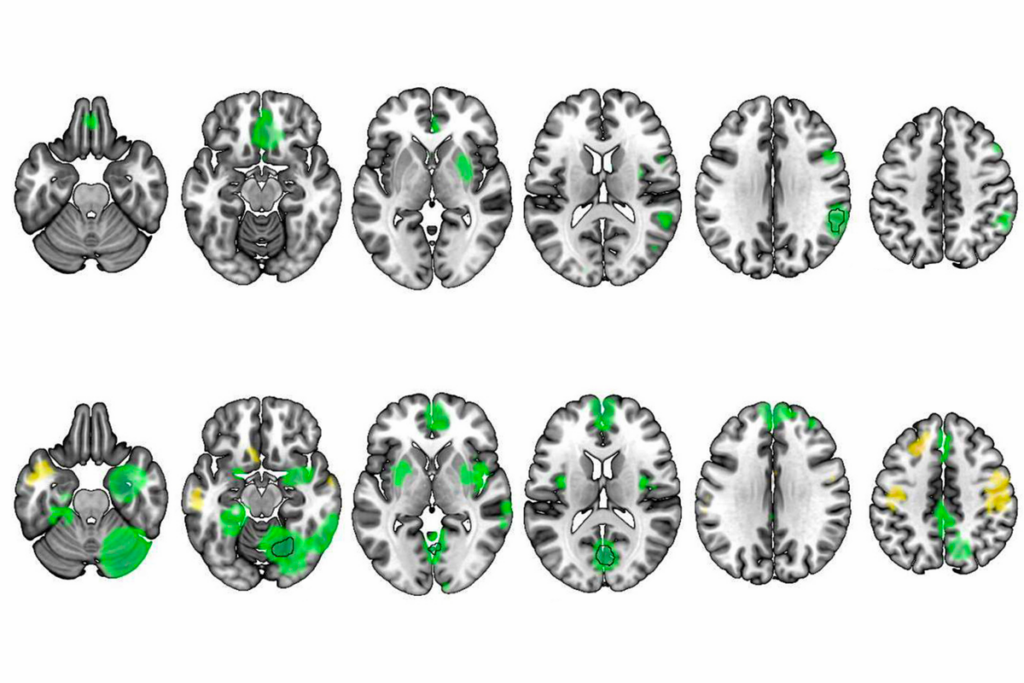

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

BCL11A-related intellectual developmental disorder; intervention dosage; gray-matter volume

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism