Growing old with autism

For many autistic adults, the golden years are tarnished by poor health, poverty and, in some cases, homelessness. Their plight reveals huge gaps in care.

K

urt remembers very little of what happened during the 4th of July weekend in 2009. Then 49, he had been in his apartment when all of a sudden he became dizzy, nauseous and unable to speak properly. The right side of his body felt sluggish, so he called a friend to take him to the hospital and then staggered to his bed. (We are withholding Kurt’s last name to protect his privacy.)When Kurt’s friend arrived, he phoned Kurt but got no answer. Peering through a window, the friend spotted Kurt in bed, not moving, so he ran to find the building manager, who let him in.

The friend helped Kurt to the car and drove him to the hospital, about a mile away in Silver Spring, Maryland. A neurologist there determined that Kurt had had a stroke. His speech was garbled, and he had trouble moving one of his legs. After talking with Kurt, the doctor jotted down an additional diagnosis code — for Asperger syndrome, a form of autism. (The syndrome has since been subsumed into the autism diagnosis.)

Kurt did not put much stock in the Asperger label at first, but it did explain a lot: his all-consuming focus on his hobbies, such as astronomy; his anxiety about changes to his routine; and his tendency to avoid eye contact. His parents had even sought medical help for these behaviors when Kurt was a child, but they had never received an explanation for them. “There were things in my childhood that people noticed about me and didn’t know what it was, but it turns out I have Asperger’s,” Kurt says. “It surprised the hell out of me, because I’d never heard of anything like that.” Years after the stroke, a psychiatrist confirmed Kurt’s autism diagnosis.

The stroke pushed Kurt to take better care of himself. Before his stroke, he had not been to the doctor in two years — after quitting his job at a community charity group in 2007, he had forgotten to sign up for health insurance. Now, at age 60, Kurt has seen specialists for a number of conditions: He takes medications for diabetes and hypertension, and in December he began showing signs of kidney disease. Though Kurt is not yet a senior citizen, “his medical problems age him,” says Elizabeth Wise, Kurt’s psychiatrist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

Most autism research has been focused on children, so there is little information about autistic adults, let alone older autistic adults like Kurt. But emerging research suggests that autistic adults are at high risk of a broad array of physical and mental health conditions, including diabetes, depression and heart disease. They are also about 2.5 times as likely as their neurotypical peers to die early. The reasons for these grim statistics may range from missed medical appointments and medication doses to a lifetime of social slights and discrimination. Many autistic seniors also bear the consequences of having been undiagnosed for most of their lives. In a 2011 study, researchers found that 14 of 141 people in a Pennsylvania psychiatric hospital had undiagnosed autism, and of those, all but 2 had been misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. Diagnosing adults with autism is tricky because the tests are designed mainly for children; they also ask for details about early life — which, for older adults with deceased parents, may no longer be available.

Without a diagnosis, older adults with autism cannot access many services that could help them secure housing and medical care. Even after a diagnosis, those who have little income and no one to care for them may lose their housing and be sent to group homes, where insufficient care and support can leave medical problems untreated. Loss of parents and other caretakers can also shatter a structure of emotional and practical support, triggering a slide in both mental and physical health. “I think a lot of the reason why we end up having more health problems is because in adulthood we don’t get the support we need to manage our healthcare,” says Samantha Crane, legal director of the nonprofit Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

Better diagnosis, access to care and adequate support are all essential to improving the outlook for this neglected group of seniors, experts say — although there are few studies to support these observations. “There really is no systematic research on autism over 65, and so we really don’t know the nature of the problems,” says Joseph Piven, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “But the ‘pig in the python’ is headed our way, with the aging population and recognition of higher prevalence of autism than was once thought.”

Unfriendly world:

M

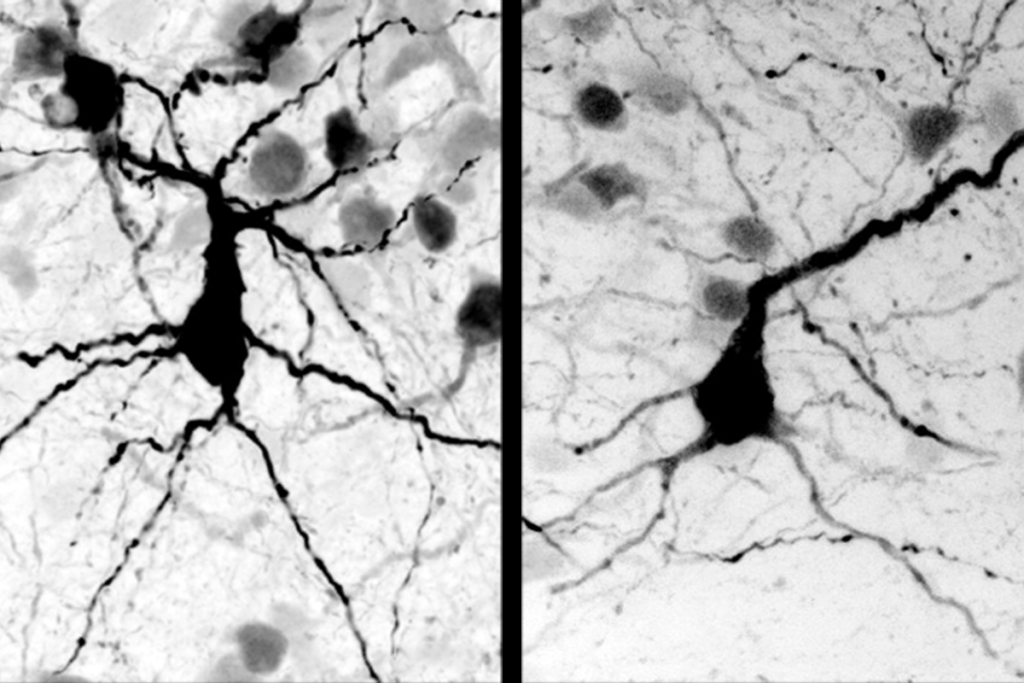

ore than half of people with autism have four or more co-occurring conditions — from epilepsy and gastrointestinal conditions to obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression. Most of the data on autism and co-occurring conditions come from studies of children; only about 2 percent of funding for autism research supports studies on the needs of adults, and most of that money goes to studies of young adults, according to a 2016 report. The past five years have seen a small surge in research on older people, and the findings are alarming. Autistic adults have elevated odds of myriad conditions, ranging from allergies and diabetes to cerebral palsy, according to a 2015 study. They also have strikingly high odds of various psychiatric problems, including schizophrenia and depression. Another 2015 study reported that signs of Parkinson’s disease are about 200 times as common among autistic people over 40 years old as among typical adults aged 40 to 60 years.One big study last year took a broad look at the health of autistic seniors, drawing upon data from nearly 4,700 seniors with autism and more than 46,800 typical seniors. It found that autistic adults are significantly more likely than typical adults to have 19 of the 22 physical health conditions the study looked at, as well as 8 of the 9 mental health conditions. For instance, adults with autism are 19 times as likely as controls to have epilepsy and 6 times as likely to have Parkinson’s disease. They are 25 times as likely to have schizophrenia or other forms of psychosis, 11 times as likely to have suicidal thoughts or engage in intentional self-injury and 22 times as likely to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

These findings provide snapshots of people’s health at particular points, but researchers have little information on how these issues may unfold over an autistic person’s lifetime. “We know a lot about children and their symptoms, but not what happens when they’re 40, 50 or 60 — what we call trajectories,” says Sergio Starkstein, a psychiatrist and medical scientist at the University of Western Australia in Perth.

Older autistic adults may be prone to health problems for some of the same reasons younger ones are. Autism shares genetic roots with conditions such as schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and several types of cancer, and evidence suggests a biological link to Parkinson’s disease as well. Some autism traits can also pose health risks, and those risks can compound over time. For instance, unusual food preferences and a tendency to be sedentary, both common among autistic people, can ultimately take a toll. Kurt was obese when he had his stroke and says it was a factor in his winding up in the hospital. “It was a real wake-up call to lose weight,” he says. “I have lost 75 pounds, but I’m still fat.”

Medication can also have unintended effects. People with autism often take antipsychotic drugs such as aripiprazole that can cause weight gain and high blood pressure — and raise the risk for diabetes and heart disease. Antipsychotic drugs can also lead to symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. And one condition can often beget another: Persistent sleep apnea, which may be common in children with autism, increases the risk of diabetes and heart conditions.

But perhaps the most insidious, and under-appreciated, culprit is a world that often feels unfriendly to those who are different. Many autistic adults engage in camouflaging — trying to act like a neurotypical person by hiding autism traits. This masking can be stressful — and stress can raise the risk of heart disease, stroke and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Without adequate support, some autistic adults may also experience ‘burnout,’ a phenomenon characterized by chronic exhaustion, loss of skills and other consequences. “Looking at health in older adults with autism can tell us something about the result of a lifetime of the lived experience of being autistic, of the discrimination that comes with being autistic,” says Lauren Bishop, assistant professor of social work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Social isolation can exacerbate these health issues. Loneliness, feelings of alienation and a sense of rejection are common among autistic adults and can lead to depression. Access to counseling and group activities also drastically declines after high school, leaving many autistic adults adrift. “They’re underemployed, and they miss out on social opportunities,” says Christopher Hanks, medical director of the Center for Autism Services and Transition at Ohio State University in Columbus. “They don’t get to participate in the things that will often get the rest of us out of the house and keep us healthier, emotionally and physically.”

Jo Qatana Adell, 63, was diagnosed with autism more than six years ago. She has had a diverse array of jobs — retail, food preparation, stringing pearls and selling books. But she has never been able to hold down a job for more than two years because, she says, her bosses and coworkers cannot stand to be around her. “I’ve got a really strong personality, and when I’m working or stressed, I talk too much,” she says. “I really suck at masking.”

Air-traffic control:

S

ocial isolation and lack of support cause many autistic adults to miss out on preventive care and early treatment, often because they lack the organizational and planning abilities — a set of skills called ‘executive function’ — to schedule and keep medical appointments or even know when they need them. “We know executive function is a difficult area, and adulthood stresses this because adulthood tends to be less structured, and there will tend to be less support,” says Steven Kapp, a lecturer in psychology at the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom who is autistic.Simply accessing care can be a monumental task. Kurt’s mother had been diagnosed with dementia a few years before his stroke, but luckily, his older sister Michele stepped in after the stroke to take care of her brother. She helps him live on his own, visiting him weekly to ensure he pays his bills, fills his prescriptions, keeps up his home and makes it to appointments. She also helped him verify his enrollment in several government assistance programs. She likens this work to that of an “air-traffic controller” and says she adopted “the assertiveness and persistence of a New Yorker” in navigating the confusing public-assistance systems. Still, she found it extremely difficult to find him a doctor. Many did not take government insurance, only saw autistic children or were not accepting new clients. In early 2016, Michele and Kurt discovered a specialty center at Johns Hopkins University, just a 45-minute drive from Kurt’s home. He was lucky to get in: According to Wise, the waitlist for new clients at the Hopkins center now ranges from one to two years.

Part of the difficulty in finding doctors to treat autistic adults is a lack of expertise — and doctors’ own hesitation. “A lot of physicians will say, ‘I don’t know enough about this to treat you,’” Bishop says. A 2012 survey in Connecticut found that only about one in three doctors in the state has been trained to care for adults with autism, and a 2015 survey in California reported that less than one in three mental health professionals there feels confident caring for autistic adults. And in Australia, Starkstein says he often has trouble admitting older adults with autism to the public hospital where he works. “It is extremely difficult to get a bed for them,” he says. A lack of specialists results not only in poor outcomes but also in long hospital stays, “something that institutions don’t like at all,” he says.

Adell has luckily been in good health so far, but if she ever does need to access care, she says, she may have no one to be her air-traffic controller. Her parents died years ago, and she does not get along with her siblings. Her living situation is precarious: She was evicted her from her apartment six years ago after a dispute over the rent. Unable to find affordable housing in the California Bay Area, she became homeless. She has managed to stay off the street so far by working as a live-in dog-sitter and crashing with friends. But this nomadic, uncertain lifestyle is incredibly stressful, she says. One place she stayed in was a horrible mess, and the friend who lived there could not manage even basic self-care. She ended up with a gastrointestinal condition that led to a 20-pound weight loss. She worries, too, that she is running out of friends — either because they have died or because she has outstayed her welcome.

After four years of trying, Adell could not get Supplemental Security Income, a federal program for people who are either aged 65 or over or have a disability. She has applied for subsidized senior housing but is not optimistic about that, either: “I get to fill out forms to be entered into lotteries to be put on waiting lists, and then I get to wait for enough people to die so I can get a studio apartment, possibly hundreds of miles away from my resources and support.”

Global gaps:

A

dell’s troubles finding and keeping housing seem far from unusual among her autistic peers, although the evidence is anecdotal. Even if they can afford their residence (and many cannot), they may forget to pay their bills or get evicted for hoarding. And like Adell, many older autistic people do not have family members to help them and to coordinate their care. Because they often do not have children, when their parents are gone, so too is their entire support system. If a court determines that an autistic adult cannot manage on her own, she might wind up shunted to an unfamiliar relative or assigned a professional guardian, leading to a dramatic loss of autonomy, Crane says.Many court-appointed guardians move their charges into a nursing home or other group living facility, cutting them off from their community and friends. Some people, especially those with intellectual disabilities, wind up stuck in facilities for people with dementia, even if they do not have it themselves. The trauma of these changes can lead to behavior problems, depression and long stays in psychiatric hospitals, says Kyle Jones, associate clinical professor of family and preventive medicine at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. The disability community advocates for keeping everyone out of nursing homes, but experts say many autistic seniors are given no other option. “We knew it was wrong for people with disabilities to be institutionalized on a massive scale, but we seem to look the other way when they’re older,” Kapp says.

The problem appears to be global. Like the United States, the United Kingdom lacks a strategy for providing health and social care for older autistic adults, according to Rebecca Charlton, a psychologist at the University of London. And the same is true for Argentina and Australia, Starkstein says. Still, the plight of these older citizens is urgent. “I think not just in medicine, but in all of society, we need to say, ‘How can we make the world work better for them so they can function to their highest ability?’” Hanks says.

Autistic adults are participating in at least one effort to find a solution. Four adults on the spectrum are collaborating with researchers at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands to study a group of 200 adults ages 30 to 80 over two to three years. The researchers collect information at two time points on the adults’ cognition, physical and mental health, and various lifestyle factors to glean an understanding of how these change over time. The autistic collaborators help focus the study on issues that are most pertinent to autistic people, says the lead investigator, psychologist Hilde Geurts. She and her colleagues also launched a therapist-led discussion group for older autistic adults, called “Older and Wiser.” In six sessions, participants over the age of 55 meet to talk about how they deal with aging, communicate with their doctor and other challenges. Geurts is still analyzing the results of the first two years of the program, but initial findings suggest that the meetings boost participants’ self-esteem.

Perhaps the best help autistic adults can find, at least in the U.S., is housed in a nondescript tan building just off a freeway four miles from the University of Utah. The Neurobehavior Healthy Outcomes Medical Excellence (HOME) program provides a comprehensive array of services for 1,200 individuals with a developmental disability, including about 100 autistic people over 65. A psychiatrist and a primary care provider are often both present at visits, as many health concerns straddle the line between mental and physical, says Jones, who directs primary care at HOME.

Other experts at the center provide talk therapy for those who are able and willing to talk, or they help manage troublesome behaviors. Doctors budget an hour for each appointment, compared with the typical 15 to 20 minutes at most healthcare centers. HOME also employs case managers who coordinate care outside of the clinic and help autistic people and their families access resources, such as financial help for housing and short-term help for primary caregivers. Case managers also may come up with creative solutions for clinical challenges. The program is affordable, too, because it accepts government support and insurance.

The clinic Kurt goes to, the Adult Autism and Developmental Disorders Center at Johns Hopkins, offers some of the same benefits. At his Thursday appointments, a nurse checks his vitals, and depending on the day, he may see also see an occupational therapist and a mental health therapist or psychiatrist. The staff involves family members in his care, Michele says, and Kurt sees the same therapists and nurses on each visit, so they know him, his history and his needs.

Dotting the country with replicas of HOME or Kurt’s clinic could provide much needed support for older autistic adults, Jones says. For that to happen, though, regulators and policymakers must first recognize that this population has unique needs. And the political will seems to be sorely lacking. U.S. legislation called the CLASS Act, which would have supported long-term services for people with disabilities as they age, was never fully implemented and was repealed in 2013, and no similar bills are in the offing. “[The act] was eviscerated because it was expensive,” Crane says. “But of course, it is expensive to put people in nursing homes as well.”

Meanwhile, Adell has to hope that her health holds up, and Kurt is unsure how he would fare without Michele or his other siblings to care for him. “I would probably be not nearly as well off,” he says. “When you get older, things are pretty bad.”

Syndication

This article was republished in The Atlantic.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025

Neuroscience’s leaders, legacies and rising stars of 2025