Welcome to the second edition of Going on Trial, a monthly newsletter that rounds up the latest in clinical trials and drug development for autism and related conditions. This month’s issue highlights the federal Orphan Drug Act in the United States, which turned 40 in January, and new orphans for Rett and fragile X syndromes.

Thank you to everyone who read our first edition and subscribed to the newsletter, especially those of you who sent me tips and feedback. This newsletter is still pretty new, and I want it to reflect the needs of the research community, so please email me at [email protected] with your ideas on how to improve it. And don’t forget to subscribe to receive Going on Trial in your inbox every month.

New rare-disease orphan drugs:

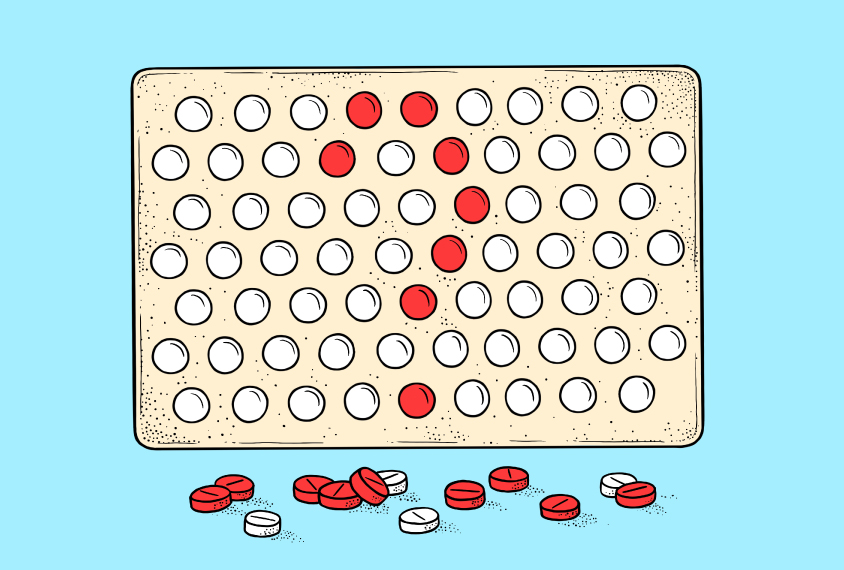

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted orphan drug designation to oral ketamine for Rett syndrome this month, as well as psilocybin and the experimental drug blarcamesine, both for fragile X, in November. This status, created by the Orphan Drug Act, aims to foster drug development for rare conditions that the pharmaceutical industry has “orphaned” because of a lack of financial incentive.

To qualify as an orphan drug, a compound must target a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people. Once the compound qualifies, its maker benefits from tax credits for clinical trials and exemptions from certain FDA fees — discounts that make its development a bit less of a gamble.

“I’m sure it isn’t the only reason that companies have been willing to step into that space, but it offers some offset to the risk,” says Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, professor of developmental neuropsychiatry at Columbia University.

The Orphan Drug Act also grants drugmakers seven years of market exclusivity. “There might not be an incentive from a financial standpoint to do it otherwise,” says Eric Hollander, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. “To make that kind of investment, you want to be able to recoup those costs on the other side.”

Many orphan drugs, including ketamine, are already FDA-approved to treat other conditions — or are at least known entities, in the case of psilocybin. The same oral ketamine formulation newly designated for Rett, for instance, has orphan drug designations for four other conditions.

In some cases, this repurposing can go so far as carving out new subgroups of patients with the same condition the drug was initially approved for, earning orphan drug status again for the same drug — costing the U.S. federal government billions of dollars in tax credits, according to an investigation by Kaiser Health News. And orphan drugs tend to be expensive, as companies take advantage of their period of market exclusivity, causing problems for people whose insurers are reluctant to shell out for the treatments.

Getting a drug named an orphan doesn’t necessarily make approval easier, though, Hollander says. Orphan drugs must go through the same process as any other drug, including multiple rounds of clinical trials. In fact, recruiting participants with a rare condition can be a big challenge because a sufficiently large sample may be spread across the country, Hollander adds.

Orphan drug status can be a double-edged sword, too, he says: Clinical trials can contribute to increased awareness and diagnosis of a rare condition, which could nullify a condition’s orphan status. “Autism is a good example of that,” he says. “Now that there’s more awareness and there’s more screening, we’re identifying a lot more people, so now it’s 1 in 44 individuals. It’s no longer considered a rare disorder — it’s considered a relatively common condition.”

A cooling climate:

“Venture capital investment in biotech hit a record high of $51 billion in 2021, and the NASDAQ Biotechnology Index reached an all-time peak in September of that year,” my colleague Angie Voyles Askham writes in Spectrum this month.

“Since then, however, the mood has soured. Between September 2021 and mid-February of this year, the same NASDAQ index had dropped by 23 percent. Venture investing in biotech fell to a more routine $37 billion last year, a trend that has so far continued into 2023. Funding for companies targeting brain-based conditions — including autism and Rett syndrome, which saw unprecedented numbers of financings in 2020 and 2021 — has dipped back down to pre-boom levels.

“Faced with this downturn, many biotech companies began cutting costs or closing up shop — at least 29 have announced layoffs since the start of this year. Others, however, are turning to new partnership and funding models that have the potential to reshape the field.”

Read more in “Biotech downturn hurts companies targeting autism-linked conditions.”

Drug samples:

- The company testing NRTX-1001, an experimental cell therapy for focal epilepsy, confirmed at the beginning of February that it laid off a quarter of its staff, citing a tight funding environment. Eight days later, the FDA cleared the company — San Francisco-based Neurona Therapeutics — to continue enrolling participants in its ongoing phase 1/2 clinical trial, based on promising data from its first two patients. The FDA also gave Neurona the go-ahead to expand its trial to include people whose epilepsy originates in the dominant side of the mesial temporal lobe, in addition to the non-dominant side it was initially cleared to study.

- An experimental Rett syndrome gene therapy is set to embark on a phase 1/2 trial this year. The therapy, called NGN-401 and developed by New York-based Neurogene, improved survival rates and phenotypes in animals modeling Rett syndrome.

- In male mice modeling Rett syndrome, blocking the fat hormone leptin with a drug or genetic manipulation improves breathing and movement issues, supports healthy body weight, and prevents the usual degradation of overall health, according to an unpublished study posted to bioRxiv in February.

- A cannabis-based fragile X treatment is in phase 3 trials, and an interim analysis presented last year hinted that it had improved social behavior and eased some fragile X traits. But independent experts have voiced concerns about whether it will be affordable and show enough benefit over the current standard of care for fragile X syndrome, Clinical Trials Arena reported in January.

- People with epilepsy have begun receiving an experimental drug aimed at increasing their natural levels of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) as part of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 trial sponsored by New York-based Ovid Therapeutics.

- The most common psychotropic medications prescribed to autistic people in Turkey are the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and aripiprazole, followed by the anticonvulsant drug valproic acid, according to a February study in International Clinical Psychopharmacology.

- Fragile X model mice treated with the experimental antipsychotic drug pirenperone show increased expression of FMR1, the gene implicated in the condition. Researchers identified this drug as a candidate through a data-driven screening method using genetic samples from people with and without fragile X.

- Of the 210 drugs the FDA approved between 2018 and 2021, 21 showed no significant benefit over a placebo in one or more of their primary outcomes in clinical trials, according to a study in JAMA Internal Medicine.

- The blood pressure drug bumetanide continued to show no significant benefits for children and teenagers with autism, according to a January reanalysis of data from a phase 2 trial that published its initial results in 2021. Two subsequent phase 3 trials were terminated early in 2021 after the drug failed to show benefit over a placebo.

And that’s it for our second edition of Going on Trial! Be sure to subscribe so you can receive this newsletter in your inbox every month.