Girls with mild autism prone to severe epilepsy

Girls with autism are nearly three times as likely as boys with the disorder to have severe epilepsy that responds poorly to medication. The findings add a twist to one of the biggest conundrums in autism: its 4-to-1 ratio of boys to girls.

Girls with autism are nearly three times as likely as boys with the disorder to have severe epilepsy that responds poorly to medication1.

The findings, published 26 June in Autism Research, add a twist to one of the biggest conundrums in autism: its 4-to-1 ratio of boys to girls. Research suggests that girls are somehow protected from autism-linked mutations. The new study hints that these mutations also lead to treatment-resistant epilepsy.

Roughly 25 percent of people with autism have epilepsy, compared with about 1 percent of the general population. In the new study, researchers found that women who have both autism and epilepsy tend to have milder autism symptoms, but more severe seizures, than do men with the disorder. The finding suggests that whatever protects women from autism does not shield them from epilepsy.

“It’s really intriguing,” says lead researcher Karen Blackmon, assistant professor of neurology at New York University.

Previous studies have shown that epilepsy affects more girls than boys with autism. The new findings serve as a warning to doctors that epilepsy in these girls may also be especially difficult to treat.

Doctors “should be prepared to try multiple medications and realize the medications might fail at the first try,” says Shafali Jeste, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study.

Seizure skew:

Blackmon and her colleagues followed 125 individuals with autism who sought treatment for epilepsy. The participants ranged in age from 2 to 35 years.

Of the 97 boys and men, 24 percent showed no response to two epilepsy drugs. By contrast, 46 percent of the 28 girls and women did not respond. They also have milder autism symptoms than the males do, according to parent questionnaires.

The researchers excluded people with known genetic syndromes linked to epilepsy, such as tuberous sclerosis. But some participants may carry variants tied to both autism and treatment-resistant epilepsy, such as a duplication of the chromosomal region 15q11.13 — which can lead to fatal seizures.

The study’s findings may be a result of the girls and women in the study carrying a disproportionate number of these severe mutations, says Elliott Sherr, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved with the study. That would skew the results to suggest that more girls than boys in general have treatment-resistant epilepsy, for example.

Still, the work sheds new light on the long-observed overlap between autism and epilepsy. “We know very little about the subgroup of individuals with [both] autism and epilepsy,” says Christine Nordahl, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the study. “This study is a great first step in exploring sex differences in this subgroup.”

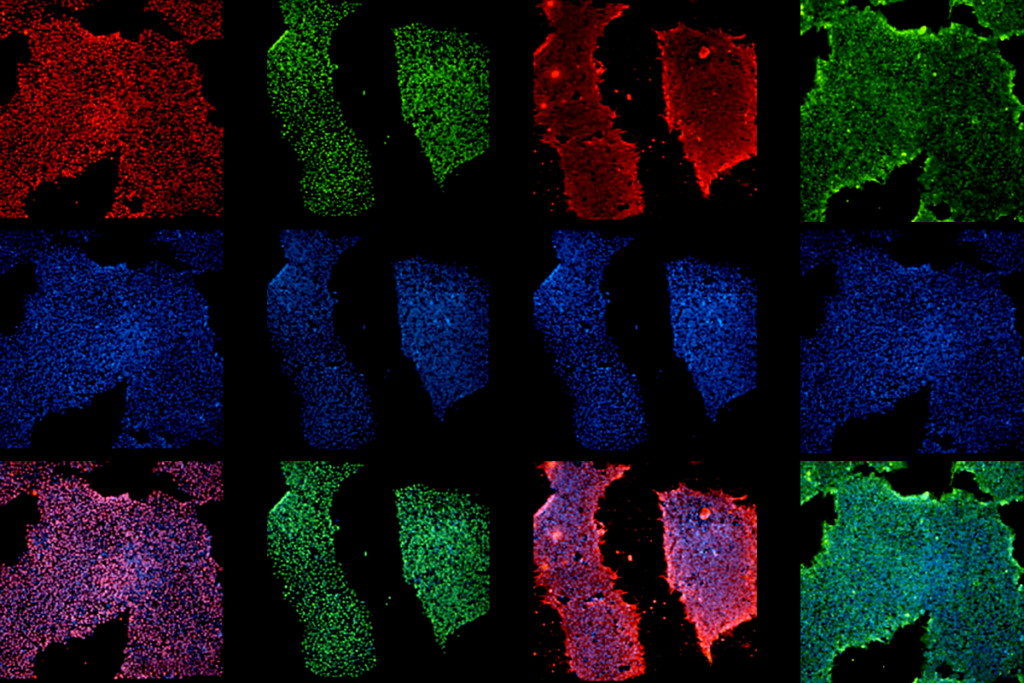

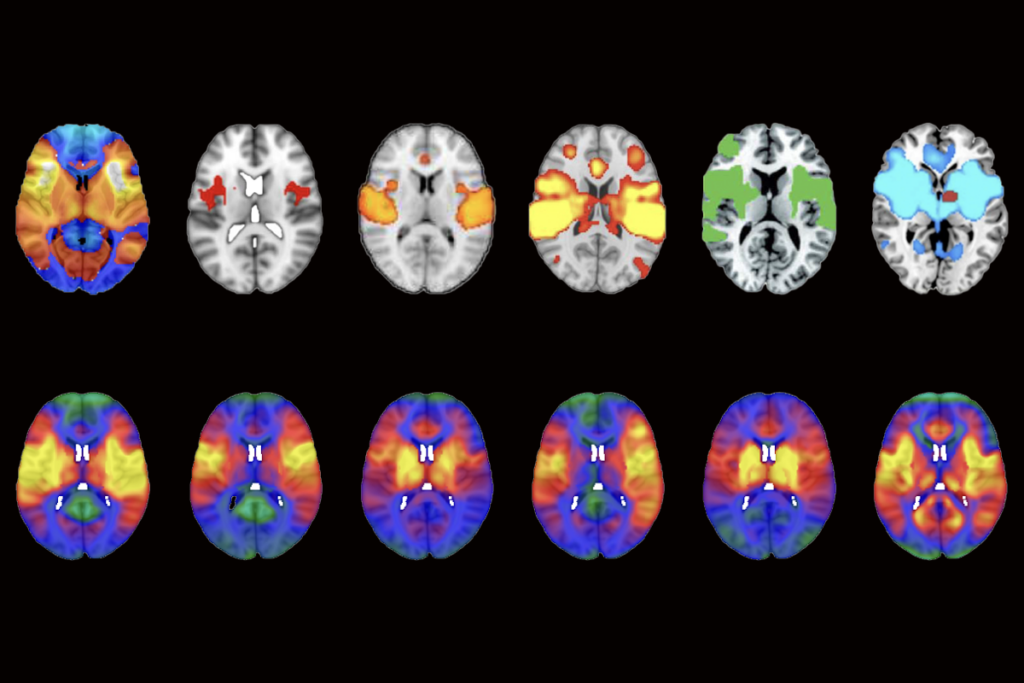

The researchers also used magnetic resonance imaging to explore the possible neurological underpinnings of girls’ susceptibility to intractable seizures.

They found that women who have both autism and epilepsy are more likely than men with both disorders to have mild abnormalities such as cortical dysplasias, in which some neurons in the top layer of the brain fail to migrate to the correct place. Roughly 42 percent of females in the study have unusual brain scans, compared with just 19 percent of males. These abnormalities track with treatment-resistant epilepsy in both genders.

Cortical dysplasias are linked to epilepsy, but some of the other abnormalities seen in the study are minor and may not be harmful. Blackmon and her colleagues are finding better ways to detect cortical dysplasias and plan to look for them across a large database of brain scans. The prevalence of these abnormalities may start to explain the connection between autism and severe epilepsy in girls, Blackmon says.

References:

1: Blackmon K. et al. Autism Res. Epub ahead of print (2015) PubMed

Recommended reading

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Profiles of neurodevelopmental conditions; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Methodological flaw may upend network mapping tool