Genetic tests of sperm may forecast odds of autism in children

Some men who have an autistic child carry mutations linked to the condition only in their sperm.

Some men who have an autistic child carry mutations linked to the condition only in their sperm, according to a new study1. In these men, genetic tests of sperm, rather than of blood, may help estimate their chances of passing the mutations to future children.

“If you look in the blood of the father, you can’t track the mutation effectively, because it can be hiding in just the sperm,” says co-lead investigator Joseph Gleeson, professor of neurosciences and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

The study involved 20 families with an autistic child; most of the children carry mutations strongly linked to the condition. Previous studies did not detect these mutations in the blood of the parents, so researchers assumed that the mutations occurred spontaneously in the parents’ egg or sperm2.

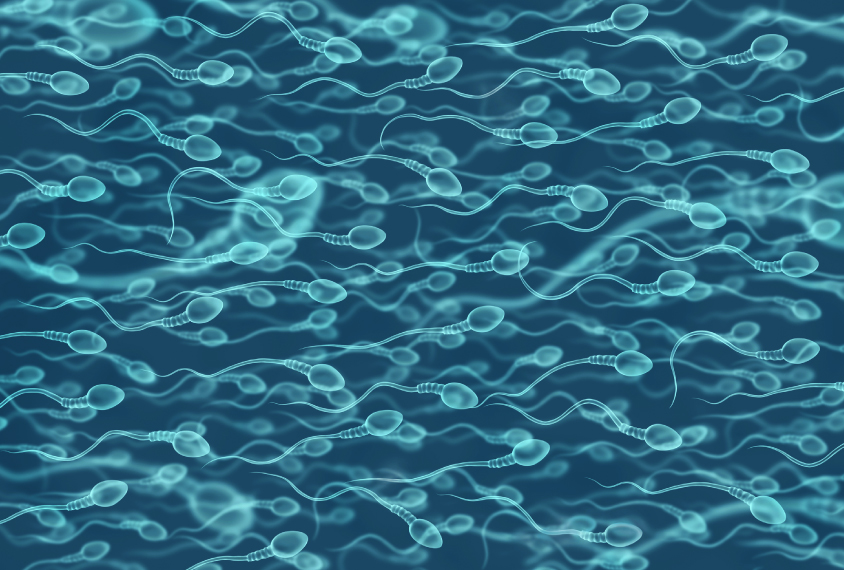

Gleeson and his colleagues used sensitive sequencing methods to analyze the fathers’ sperm. They detected the mutations in a small proportion of sperm from four of the fathers.

Spontaneous mutations found in a child are thought to have about a 1 percent chance of appearing in later-born siblings3.

The new results suggest that these odds are much higher for children of men who carry mutations in their sperm. The exact odds may depend on the proportion of sperm cells that carry the mutation.

“We need to be able to separate the few families with high risk from the others that have a negligible risk, and for that you can use sperm,” says Anne Goriely, associate professor of human genetics at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the study.

Hiding out:

Gleeson and his colleagues focused on mutations in sperm because spontaneous mutations tied to autism tend to be in a gene’s paternal copy. They used a sensitive technique that detects mosaic mutations — those that arise after conception and affect only a subset of cells.

In the four men who carry mutations in their sperm, the proportion of sperm cells affected ranges from 0.5 to 14.5 percent.

One of the men passed down a mutation in the autism gene GRIN2A to all three of his children. Only one of the children has a diagnosis of autism, but the other two have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; one sibling also has speech impairment and the other has seizures. The findings appeared in December in Nature Medicine.

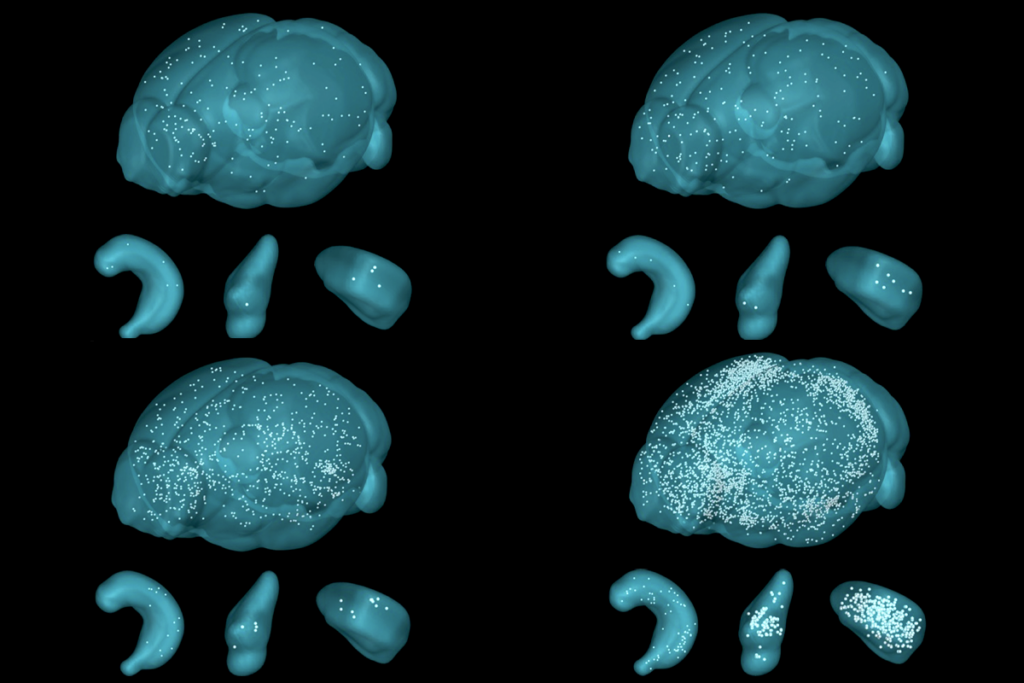

The researchers also sequenced the whole genomes of blood cells of members of eight families with autistic children. They found 912 mutations that appeared to be spontaneous in the children; 23 of these mutations turned up in a mosaic pattern in the fathers’ blood, sperm or both.

Most of the mosaic mutations appear only in sperm or are more abundant in sperm than in blood. This suggests that genetic tests of sperm may give a more accurate picture of a father’s odds of passing the mutation to his children than blood tests do.

“We anticipate that the baseline recurrence risk of 1 percent that most physicians quote can be stratified into the vast majority of patients that have near zero risk, and a small percentage that have a much higher and quantifiable risk,” Gleeson says.

The technology the researchers used is not yet widely available, but that may change. “Since we published this, we’re getting some communication from companies that are interested in maybe offering it to families and developing it as a diagnostic test,” Gleeson says.

Still, the presence of these mutations in a man’s sperm does not mean that his children will have autism — only that the odds are higher than for the general population, says Maria Chahrour, assistant professor of genetics and neuroscience at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas, who was not involved in the study. “We have to be sure that a variant causes autism if you want to use something like this in the clinic,” she says.

Gleeson says he and his colleagues are sequencing sperm from more men with an autistic child to better estimate the men’s odds of passing down a mutation. They are also testing whether the proportion of sperm cells that carry a mutation remains the same over time.

References:

Recommended reading

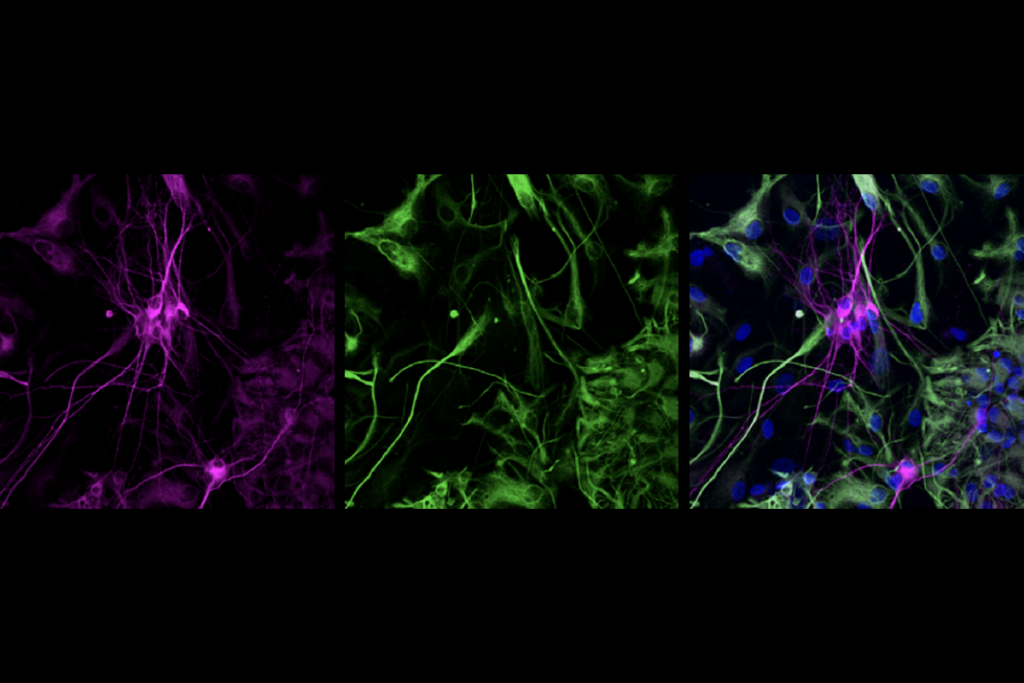

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky