Genetic registry reaps bounty of new autism genes

An analysis of genetic sequences from nearly 500 people with autism and their relatives has linked 13 new genes to the condition. It has also uncovered a genetic cause for autism in about 10 percent of the autistic participants.

Editor’s note:

An analysis of genetic sequences from nearly 500 people with autism and their relatives has linked 13 new genes to the condition1. It has also uncovered a genetic cause for autism in about 10 percent of the autistic participants.

The results are the first to emerge from SPARK, launched in 2016 to collect genetic sequences and other information from 50,000 families that have at least one child with autism. (SPARK is funded by the Simons Foundation, Spectrum’s parent organization.)

SPARK researchers analyze DNA from mailed saliva samples and medical information participants provide. Other large-scale sequencing projects have relied on clinical evaluations and blood draws, which take more time, money and effort.

In this study, the researchers analyzed exomes — the small portions of the genome that code for proteins. They linked 34 genes to autism with at least 80 percent certainty; of those, 21 had been identified by previous studies.

Most of the 13 new candidates are active in brain regions, and at developmental times, that are implicated in autism.

The results should “give the community confidence that what we’re doing in SPARK is going to produce reliable, robust data,” says Wendy Chung, the project’s leader and professor of pediatrics and medicine at Columbia University.

The study is small as exome-sequencing projects go: Previous efforts have included thousands of people with autism and their relatives. Still, experts say the findings are encouraging.

“It’s clear that with 50,000 families, we will learn a substantial amount,” says Ivan Iossifov, associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, who was not involved in the study.

Spit test:

Chung and her colleagues sequenced the DNA of 1,379 people in 457 families; the participants include 465 people with autism. They found 647 single-base variants that occur spontaneously in the autistic children — that is, they were not inherited; 85 of these variants are likely to prevent the protein from functioning.

The variants tend to fall in genes that are rarely mutated in the general population and occur in autistic people about twice as often as expected by chance — a figure in line with previous estimates.

Four genes are mutated in more than one autistic person, the researchers found. Three of these genes — CHD8, FOXP1 and SHANK3 — are top autism genes; the fourth, BRSK2, was linked to autism in May.

Of the 647 mutations, about 10 percent occur in a mosaic pattern, meaning they are found in only a subset of the body’s cells. Previous studies estimated that 7 to 22 percent of spontaneous mutations occur in a mosaic pattern.

The researchers also uncovered 273 copy number variants (CNVs) — large duplications or deletions of DNA; only 20 of these CNVs occurred spontaneously — another pattern seen in prior studies. The findings appeared in August in NPJ Genomic Medicine.

The study validates saliva as a source of DNA for these studies, says Holly Stessman, assistant professor of pharmacology at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska, who was not involved in the study. “There was some skepticism about whether [saliva DNA] was going to have the same quality.”

Robust results:

The researchers used a statistical method called TADA to analyze their results alongside mutations pulled from other datasets. Those datasets jointly include 4,773 families that have a single child with autism.

This analysis tied 34 genes to autism. The strongest candidate is BRSK2, which the study linked to autism with at least 99 percent certainty.

“Even in a relatively small sample size like this, you can find a new gene with robust genetic evidence,” says Eli Stahl, associate director of the psychiatric genomics division at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, who was not involved in the study.

Five other genes — ITSN1, DMWD, CPZ, FEZF2 and PAX5 — have at least a 90 percent chance of being involved in autism.

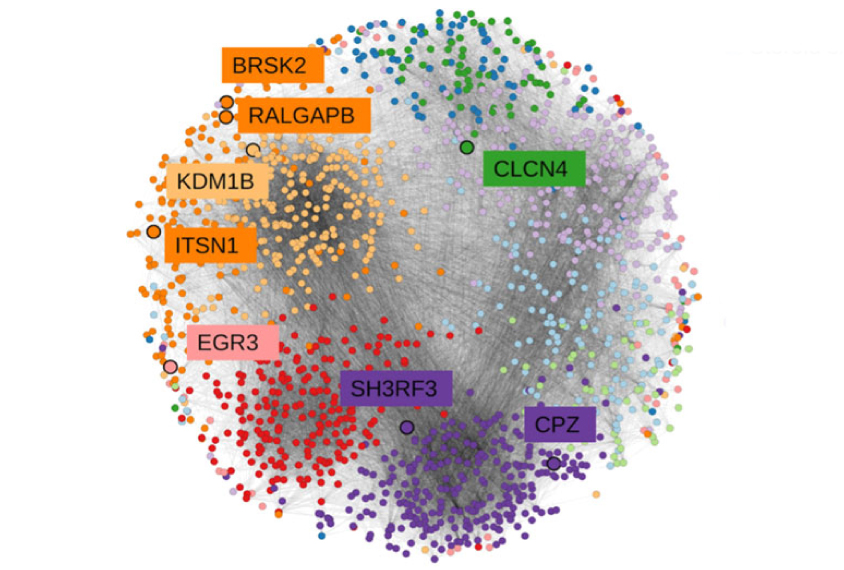

The researchers applied a machine-learning algorithm that scores a gene’s link to autism based on its expression pattern in the brain and interactions with known autism genes. Like many autism genes, most of the new candidates are expressed in neurons during mid-fetal development.

Many of them interact with other autism genes and function in processes linked to autism, such as neurons’ migration and communication.

Chung’s team has amassed sequences for roughly 27,000 participants, which are available for other researchers to analyze.

A brief history of exome sequencing

Much of what is known about the genetics of autism comes from sequencing ‘exomes’ — the protein-coding regions of the genome. Here we chronicle the short but evolving history of exome sequencing in autism.

Genetics first

The first study of exomes relies on sequences from 20 autistic children and their parents — and identifies spontaneous mutations in four genes.

Triple threat

Three landmark studies link autism to spontaneous mutations in 18 genes, based on exomes from more than 600 families.

Statistical assist

Sequences from nearly 350 autistic people and their families add statistical heft to some of the candidates. Five genes rise to the top, each with mutations in more than one autistic child: CHD8, DYRK1A, KATNAL2, POGZ and SCN2A.

Emerging candidates

By reanalyzing sequences from the April studies, researchers home in on 6 genes, including CHD8 and DYRK1A, that are disrupted in autistic people.

Double dose

A pair of studies link autism to rare, inherited mutations that hobble both copies of a gene, and that may account for about 5 percent of autism.

Genetic chunks

A large study affirms small deletions and duplications of DNA as risk factors for autism.

Top candidates

Exome sequences from more than 20,000 people identify 50 ‘high-confidence’ genes with the strongest links to autism yet.

Family ties

Rare inherited mutations appear to contribute to autism in about 10 percent of boys with the condition. And they are inherited primarily from unaffected mothers.

Short list

The list of high-confidence autism genes grows to 65; a second study whittles the list of genes with weaker ties to the condition from 500 to 239.

Narrowing the search

A closer look at 10,000 spontaneous mutations reveals that up to one-third of those previously linked to autism may not be related after all.

Patchwork pattern

An analysis of more than 20,000 exomes suggests that about 8 percent of spontaneous mutations in autistic people are ‘mosaic,’ meaning they affect only a subset of the body’s cells.

Motley crew

Mosaic mutations contribute to autism in about 4 percent of people on the spectrum, an analysis of more than 8,000 sequences suggests.

Top genes

An unpublished analysis of more than 35,000 sequences boosts the number of high-confidence autism genes from 65 to 99.

Broad spectrum

Sequences from almost 11,000 people with autism or developmental delay link 253 genes to the conditions.

Spit test

Sequencing saliva samples from 465 autistic children ties 13 new genes to autism and pinpoints the condition’s cause in about 10 percent of the children.

References:

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

This paper changed my life: Shane Liddelow on two papers that upended astrocyte research

Dean Buonomano explores the concept of time in neuroscience and physics