Genes that fit

This has been a bonanza week for the role of genetics in autism.

This has been a bonanza week for the role of genetics in autism.

First, there was the announcement that removing thimerosal, the mercury-based vaccine preservative, from vaccines had no effect on the number of cases of autism diagnosed in California.

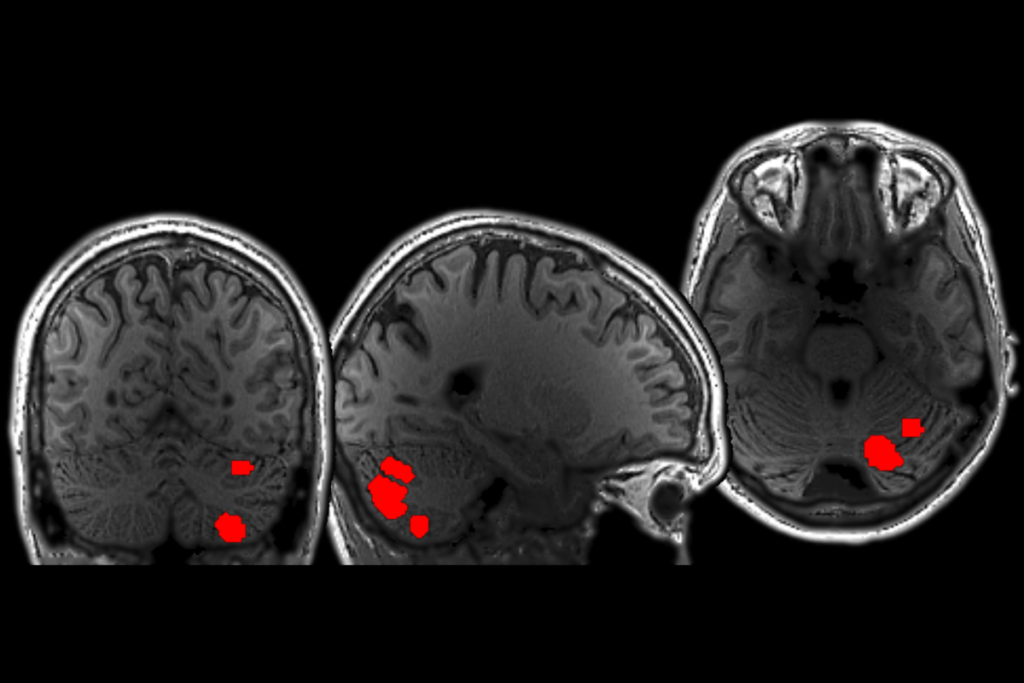

On Wednesday, Mark Daly and his colleagues reported in the New England Journal of Medicine that roughly one percent of children with autism have deletions or duplications in a part of chromosome 16 that are de novo ― that is, not inherited from their parents.

A separate team had already fingered chromosome 16, reporting December 21 in the journal Human Molecular Genetics that the loss of a small portion of chromosome 16, known as 16p11.2, is significantly associated with autism.

Then yesterday, three independent teams of researchers strengthened the case for CNTNAP2 or contactin-associated protein-like 2, thought to be involved in the ability of nerve cells to communicate with each other, as a risk factor for autism.

One study, led by Johns Hopkins University’s Aravinda Chakravarti, found that a single base change from adenine to thymine in the gene’s sequence is associated with autism. Based on data from two separate groups ― one of 145 children with autism whose families had two or more children with the condition and one of 1,295 children with autism and their healthy parents ― the team found that children with autism are about 20 percent more likely to have inherited the thymine variant from their mothers than from their fathers.

In a second paper, Dan Geschwind and his colleagues at the University of California in Los Angeles identified a different SNP in CNTNAP2 associated with autism. The researchers clarified CNTNAP2’s role in language, thought and behavior, finding that children with a longer language delay are more likely to have the variant associated with autism.

Finally, Yale University’s Matthew State and his colleagues identified several more rare mutations in CNTNAP2 found in individuals with autism. All three papers were published in the January 10 online edition of The American Journal of Human Genetics.

It’s true that each of these genetic findings only explains a small fraction of autism cases. But I find it compelling that, for instance, three different groups, using entirely different methods, all homed in on the same gene. That’s a great beginning to the new year.

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

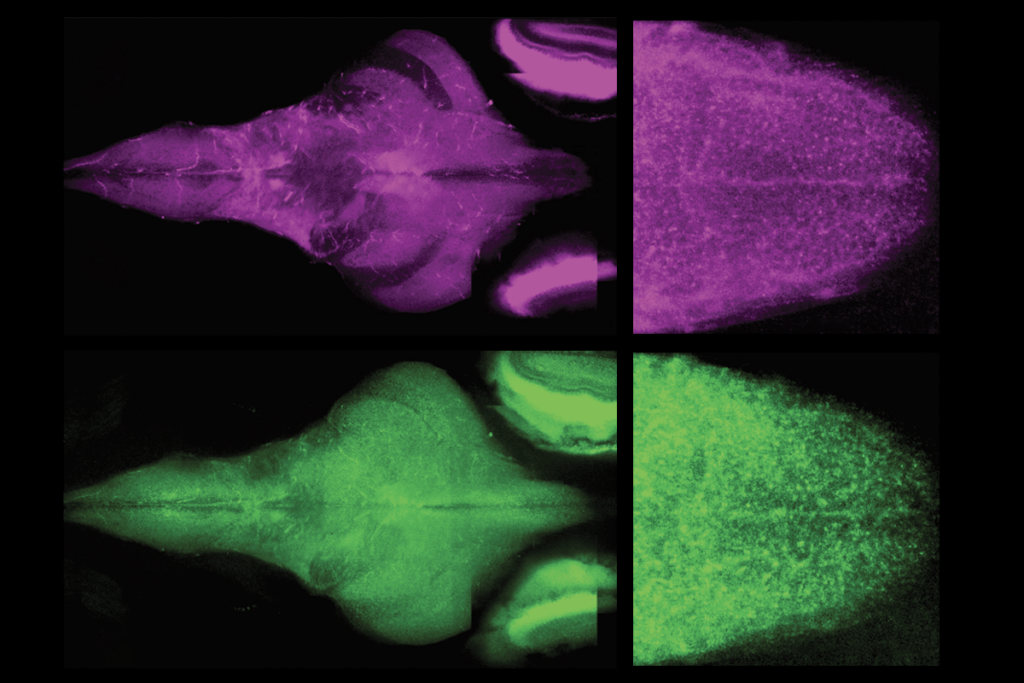

Cerebellum responds to language like cortical areas

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles