The investigational drug arbaclofen improves auditory hypersensitivity in rats missing the autism-linked gene CNTNAP2, according to a new unpublished study. The compound appears to right an imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory signaling in the rats’ brains, which is thought to play a role in many forms of autism.

Acoustic startle responses are relatively easy to measure in people and could be used in clinical trials of arbaclofen, says lead researcher Susanne Schmid, professor of anatomy and cell biology at Western University in London, Ontario.

Schmid’s team presented the findings virtually today at the 2021 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting. (Links to abstracts may work only for registered conference attendees.)

The researchers exposed rats missing both copies of CNTNAP2 to a sudden, loud tone and tracked their startle response and their rate of habituation to the stimulus — or their ability to get used to it and react less intensely over time.

Compared with controls, the CNTNAP2 rats were more startled by the sound and became less habituated to it over time. Treating the rats with arbaclofen, however, nudged both measures closer to those of controls in a dose-dependent fashion. (The Simons Foundation, Spectrum’s parent organization, holds the patent rights to arbaclofen.)

A previous clinical trial of arbaclofen failed to show significant improvements over placebo in people with autism, though some participants did make gains in some social abilities. Arbaclofen improved cognitive and social functioning in another animal model of autism, namely mice missing the chromosome region 16p11.2, a later study showed.

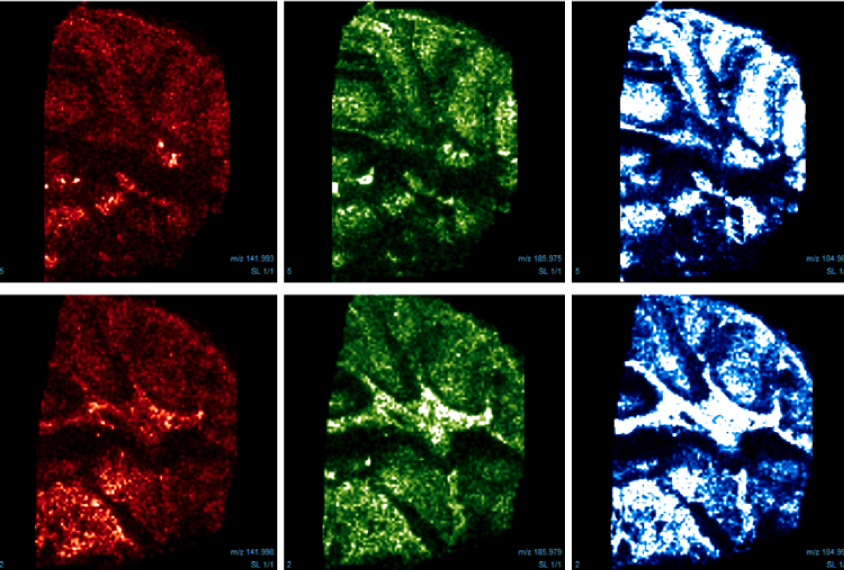

Arbaclofen binds to and stimulates a type of gamma amino-butyric acid (GABA) receptor, dampening the action of the excitatory signaling molecule glutamate. Mass spectrometry revealed that the CNTNAP2 rats had greater concentrations of GABA, glutamate and their precursor, glutamine, in the brainstem, the area involved in startle responses.

“I was generally surprised how well the phenotype was reversed, given that GABA is not the major inhibitory transmitter in the brainstem,” Schmid says. The changes seen in the rats’ brainstems may also take place elsewhere in the brain, and in areas that are more heavily modulated by GABA, she says, which may be where the therapeutic effect is occurring.

Read more reports from the 2021 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting.