Family groups play key role in advancing autism research

Families need more support from researchers in order for their heroic efforts to be optimally effective.

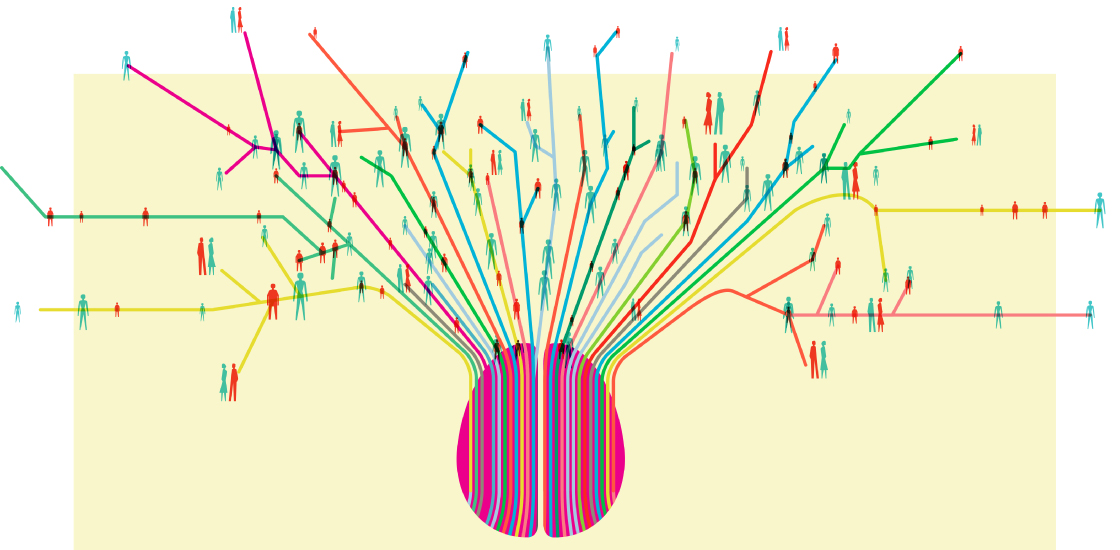

As genetic testing for autism and related conditions of brain development becomes more common, parents are increasingly receiving specific genetic diagnoses for their children1,2. These tests rarely point to a treatment, but they do allow families to form groups united by the genetic diagnosis. The groups provide families with critical support, educational resources and insight into their child’s prognosis.

The groups can also catalyze scientific progress in understanding the condition. For instance, a Facebook group for people with a mutation in a gene called ADNP, one of the genes most strongly linked to autism risk, helped to discover that the majority of these children grow all their baby teeth before their first birthday. Doctors can now use this feature to diagnose children with ADNP mutations more quickly.

Some of these small groups eventually grow into nonprofit foundations. The International Rett Syndrome Foundation represents individuals with mutations in a gene called MECP2. Mutations in MECP2 cause Rett syndrome, a severe condition related to autism. The foundation has invested more than $32 million in research since 1998. Backed by that funding, researchers have made huge strides in understanding and developing treatments for Rett syndrome.

In one landmark study, they reversed multiple neurological features of Rett syndrome in a mouse model of the condition3. And earlier this year, the foundation announced plans to launch a large clinical trial of a compound called trofinetide for children with Rett syndrome.

Broad benefits:

These sorts of foundations can also actively encourage researchers to share resources, including posting research results on preprint servers such as bioRxiv, submitting data to repositories or making tools, such as genetic mouse models, available to other teams. They also make sure the needs of the affected individuals remain the focal point — balancing, for example, vital basic science with more clinical research on treatments. But the heroic efforts of these families need support from the scientific community to be optimally effective.

For these family groups to contribute to genetic research, they must develop registries of the affected individuals alongside clinical data — and keep these data secure. They must also develop a repository for biological specimens such as blood, and maintain a curated list of the genetic variants associated with autism — as a database of MECP2 mutations called RettBASE has done, for example.

These activities require enormous effort and expense from the group members. Those leading the way rarely have formal scientific training and are often also caring for children with complicated medical needs. Because each of the groups acts in relative isolation, there is substantial duplicated effort and a lack of consistency in the resulting resources; this will only get worse as the number of genetic variants associated with autism increases.

Building tools:

Although it is important that the family groups control this research infrastructure, other segments of the autism community should take the lead in developing resources, such as databases and biobanks, that any group can use. Funding bodies and research institutions could work together on an open-source project to develop these systems. The individual groups could then customize this generic infrastructure, changing the way it looks and selecting the features most relevant to their members. This concept has been pioneered by Simons VIP Connect, which hosts a registry and biobank for several groups. (Simons VIP Connect is funded by the Simons Foundation, Spectrum’s parent organization.)

The research community could also develop tools for parents to monitor their child’s progress alongside medication changes, life events and expected outcomes. This information has clinical benefits and can increase family engagement with research and help define the common features of the condition, such as speech delay. Other tools may be more family focused. For example, a family might identify and reach out to nearby families without having to publicly disclose personal information.

Generic infrastructure would also help standardize information about features of a syndrome across groups. This information could be key to understanding the diversity of features seen in autism. For example, duplications in the 15q11.2-13 chromosomal region appear to have a greater impact on social behavior than deletions in the 22q11.2 chromosomal region, even though both regions are associated with autism4.

If we take these insights across multiple genetic conditions and couple them with parallel data from basic science — findings from mouse models, for example — we may be able to map the circuits and processes in the brain that correspond to specific features. Findings like these would help reveal related conditions and provide a strong biological foundation for developing treatments.

Along these lines, the TIGER Study is an effort to compare behaviors across genetic conditions related to autism. Allowing members of family groups to contribute directly, through standardized online tools, would boost the number of participants and help researchers assess how behavior changes over time in each child.

Group support:

But to get to there, we need more groups with a strong footing. To date, only seven groups — based on 7 of 20 genes with the strongest association with autism — have led to foundations: ADNP, DYRK1A, GRIN2B, PTEN, SCN2A, SHANK3, and SYNGAP11. This is not simply because genetic changes are rare; we expect up to 6,000 cases per high-confidence gene in the United States and up to 120,000 cases globally. Rather, it is due to limitations in making diagnoses, connecting families and the multiple hurdles involved in setting up a foundation.

The autism community should actively help families establish groups and support their early development. We should advocate for thorough genetic testing in the clinic, and collecting the results in a central repository. These steps would aid in identifying conditions that could seed family groups. Researchers should also design their studies so that relevant genetic findings are returned to the child’s doctor.

Once the family has a diagnosis, they need help connecting with other families — for example, through gene-specific social media groups. Simons VIP Connect has created these groups for genes and genetic loci that show robust association with autism, and new groups will be needed as gene discovery continues. Well-trafficked websites such as Autism Speaks and DECIPHER could also provide links to the groups so that new families can readily find them.

And to accelerate the development of groups, we not only need the technical infrastructure but also the opportunity for families, clinicians and scientists to meet. Funding groups could provide meeting places and financial support for families who cannot afford travel expenses, for example.

Helping to create and support family groups is one of the best investments of effort and resources that the autism community can make. These groups benefit a broad spectrum of people, from affected individuals and their caretakers to the research community. Collectively, they may hold the key to understanding the biological basis of autism by providing critical human context to scientific research.

Stephan Sanders is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

References:

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt