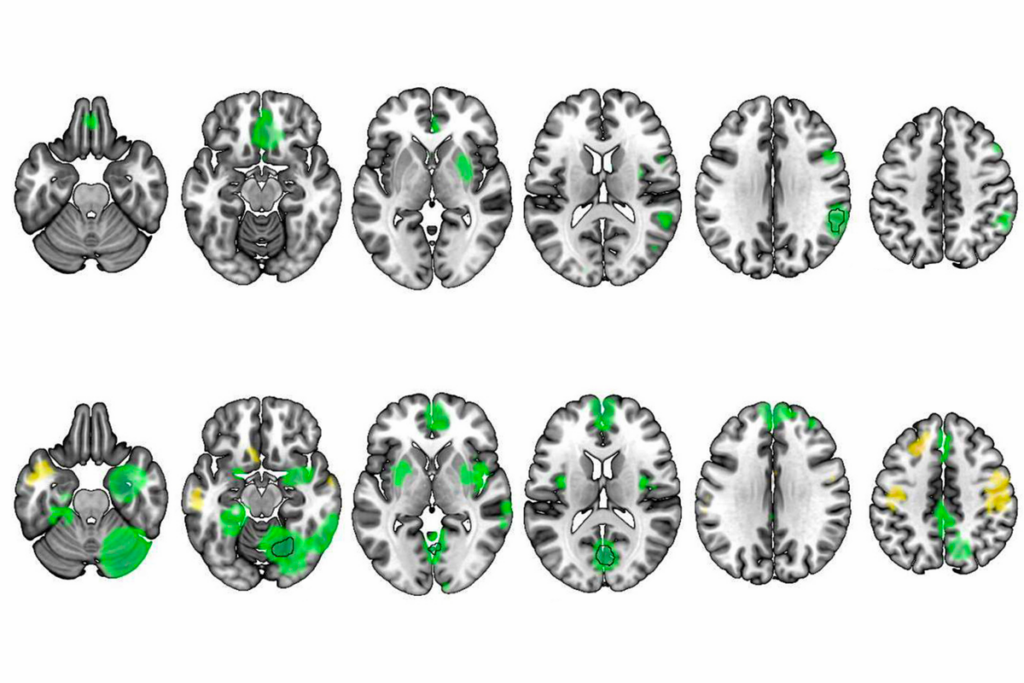

Ancestry has little bearing on the genes strongly linked to autism, according to the first genetic analysis of the largest cohort of autistic Latin Americans and their families to date. The results were posted on medRxiv on 6 January and have not yet been peer reviewed.

Of the 35 genes linked to autism in the cohort, which is managed by a consortium called Genomics of Autism in Latin America (GALA), 19 are strongly associated with autism in a separate dataset of people of European ancestry. “We conclude that the biology of ASD is universal and not impacted to any detectable degree by ancestry,” the investigators wrote in the preprint.

“It has been an open discussion in the field,” says the study’s principal investigator, Joseph Buxbaum, director of the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at the Icahn School of medicine at Mount Sinai. “And this provides a fairly clear answer.”

Diversifying autism genetics databases is “critical” work, says Maria Chahrour, associate professor of neuroscience at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the study. But Buxbaum’s conclusion may be premature, she says.

Although the fundamental biology of autism is likely consistent across people of various ancestries, saying ancestry has no impact is “a little bit of an overreach,” she says.

M

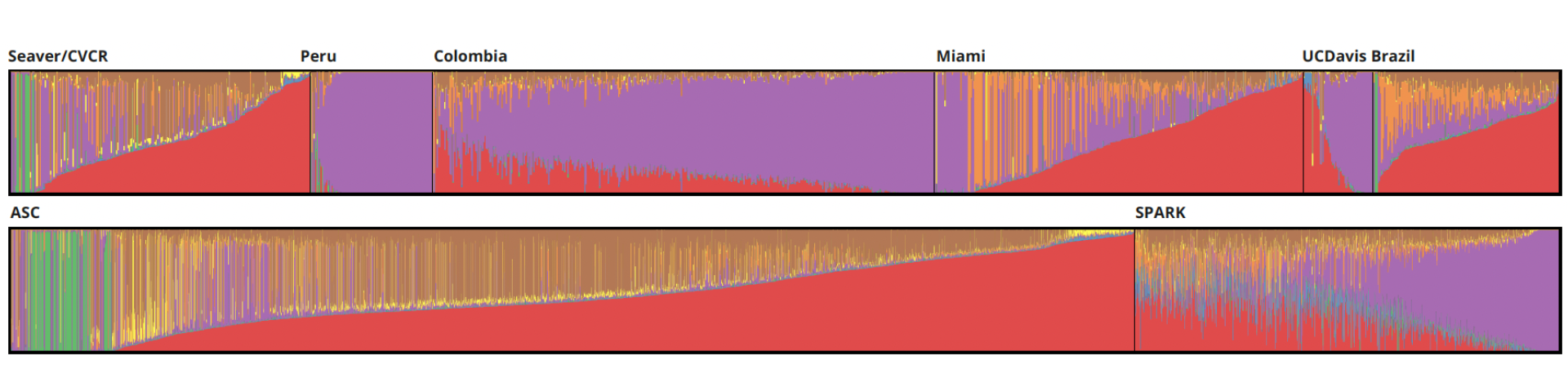

ost genetic studies to date primarily include people of European ancestry. To address this gap, Buxbaum and other scientists affiliated with the Autism Sequencing Consortium (ASC) started GALA—which includes existing data as well as funding to sequence additional families—in 2022.GALA has a total of 10 sites, located in São Paulo, Brazil; Bogota, Colombia; Central Valley, Costa Rica; Mexico City, Mexico; and Lima, Peru; as well as in California, Florida and New York. In contrast with other international gene-sequencing projects, the GALA cohort comprises a greater proportion of people who have admixed American heritage, which can include Indigenous, European, African and East Asian ancestry. The new analysis includes 1,613 Latin American people—707 of whom have autism—whose sequences have not previously been reported.

The new analysis looked at the exomes—or, in a few cases, whole genomes—of 4,450 autistic people from Latin America, along with 1,459 of their neurotypical siblings and 8,450 parents. (Data from two sites were not yet ready for analysis.)

The researchers looked for de novo variants—which are not inherited but rather occur spontaneously in a parent’s egg or sperm, or in an embryo after conception—in the GALA cohort, as well as in a previously published cohort that combined data from the ASC, the Simons Simplex Collection and SPARK, from which Buxbaum’s team removed people with admixed American heritage. (The Simons Simplex Collection and SPARK are funded by the Simons Foundation, Spectrum’s parent organization.)