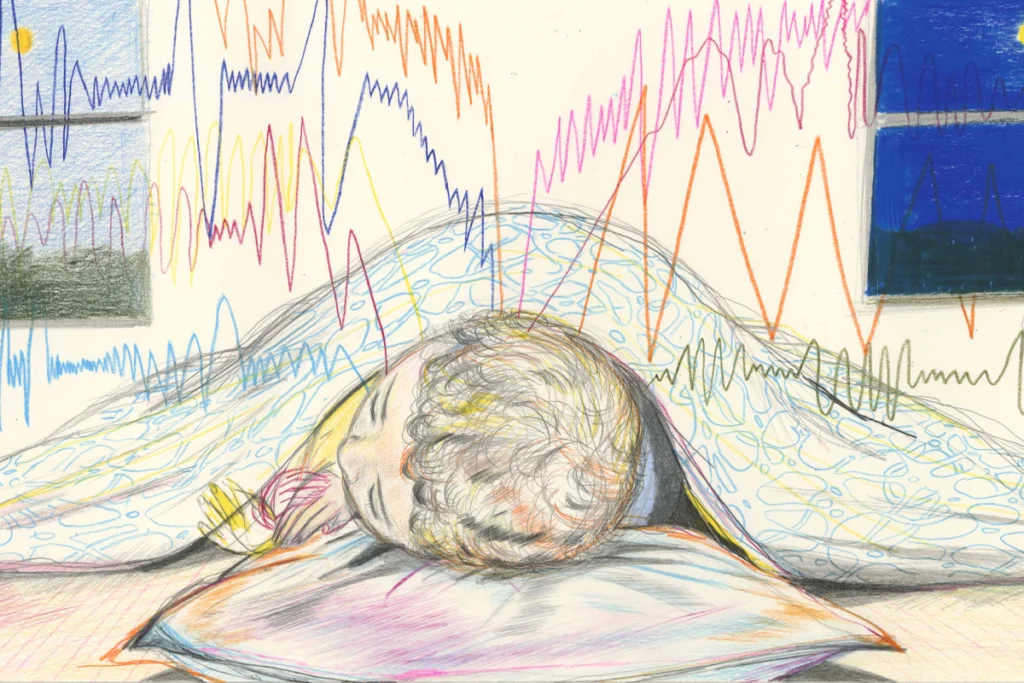

When Lilita Gigena was just 3 months old, one of her aunts spotted something unusual: The baby did not follow people with her eyes, as babies typically do by that age. Neither Gigena’s parents nor her pediatrician in their hometown of Córdoba, Argentina, had noticed anything out of the ordinary about the newborn. But her aunt suggested they take the baby to an ophthalmologist for an evaluation.

Gigena’s parents were stunned by the results: Their baby was blind. The nerve that conveys visual information from the eyes to the brain had not formed completely, they later learned, leaving Gigena able to see only vague shapes of light and dark.

They enrolled Gigena in a local school for the blind, but by the time she was 6 years old, it was clear that she was not thriving there. “The other children were reaching milestones in language, in play, in socialization,” says her mother, Lilian Funes, a teacher. “And Lilita wasn’t reaching them. She wasn’t making friends, and she didn’t communicate well.” Instead of speaking Spanish, Gigena used a made-up language that only her parents could understand.

Gigena saw a parade of specialists in Córdoba and Buenos Aires: “Doctors, neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, parapsychologists,” Funes says. “No one had the answer.” For a while, the family gave up. Then, when Gigena was 15, she received a second diagnosis that finally helped to explain some of her challenges: autism.

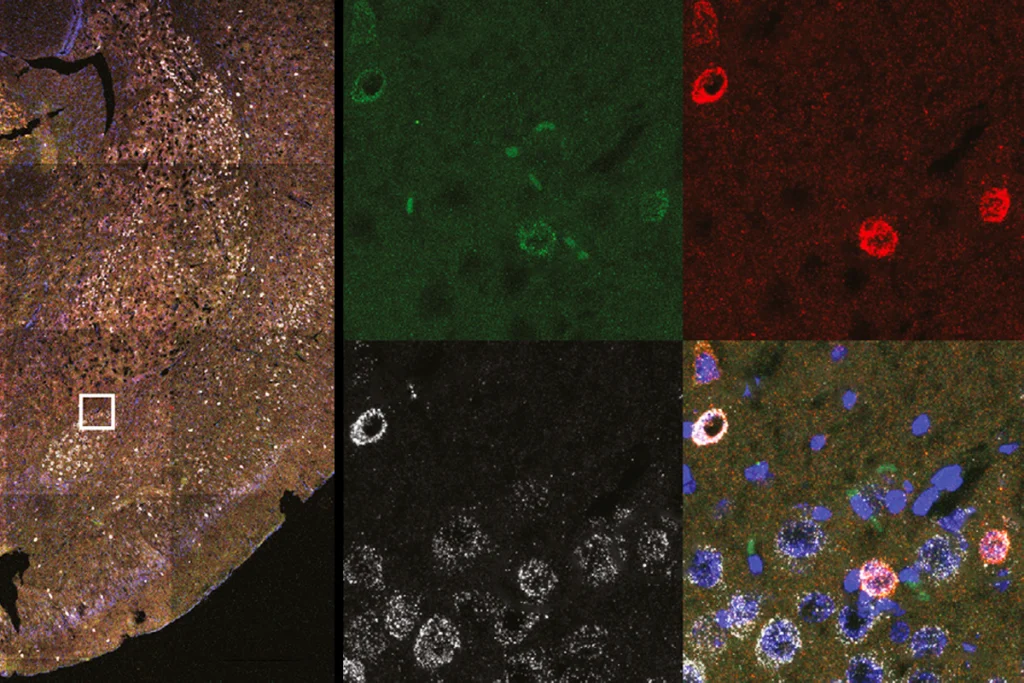

Gigena, now 43, is far from unique. Autism is at least 10 times as common among blind people as it is among the general population, studies show. And children with autism may also be more likely to have vision problems than typical children are.

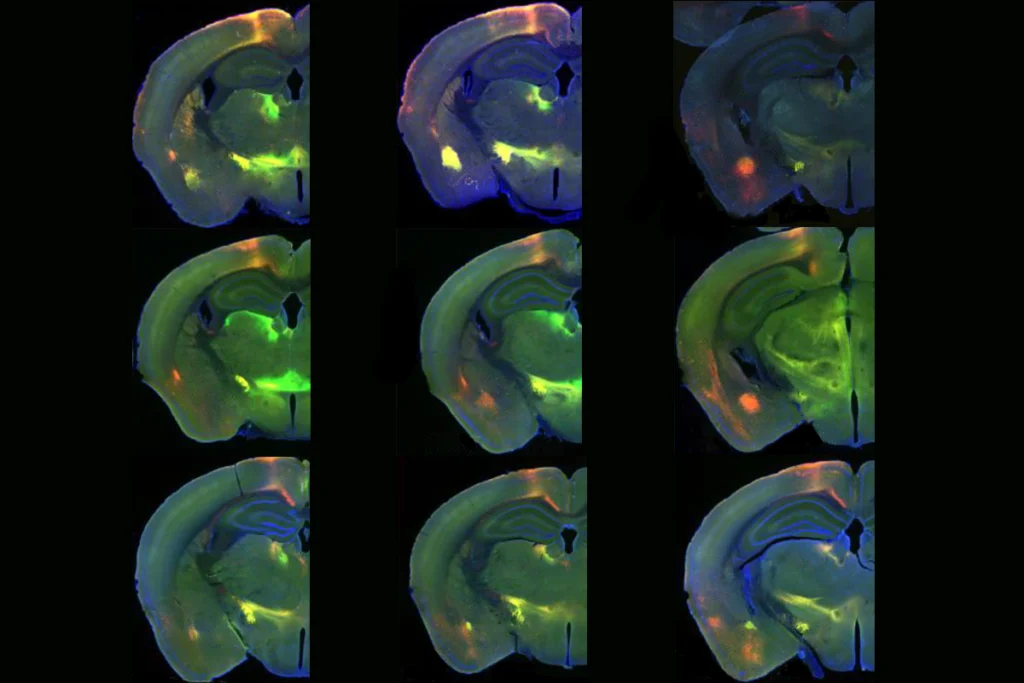

There are a variety of possible explanations: A lack of visual input may disrupt some aspects of social development and lead to autism traits, for instance. Vision is the primary way that most infants learn from others, and the main force that sculpts the social brain in the first year of life. Vision is also essential to many of the social skills people with autism find challenging — for example, directing your gaze in concert with someone else or reading facial expressions and body language. “We’re visual animals,” says Rubin Jure, the pediatric neurologist who diagnosed Gigena’s autism and still sees her in his Córdoba-based practice.

Even the metaphors we use to describe social skills, such as ‘perspective-taking,’ often involve vision, yet no one knows for sure why autism and vision problems tend to overlap. “Kids with autism do have a lot of sensory abnormalities. And vision obviously is a sensory system,” says Melinda Chang, a pediatric ophthalmologist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California. “But there’s not a lot of work to understand how visual disorders in autism could affect their development.”

Some researchers argue that the link is spurious and that autism-like behaviors in blind people stem solely from their lack of sight, not autism. Likewise, vision issues in autistic people could reflect differences in the brain that accompany autism, not eye problems per se.

Regardless, studying autism in visually impaired people could help scientists understand how aspects of the condition might overlap with vision or the visual system, Chang and other experts maintain. And attention to this population is already leading to sharper instruments for diagnosing autism in blind children, so that the next generation of families does not have to wait as long as Gigena’s did for answers.