A new funding initiative seeks to accelerate the development of treatments for people with profound autism, and eventually for other autistic people. ARIA, or Aligning Research to Impact Autism, is funded by the Sergey Brin Family Foundation, which also supports research on Parkinson’s disease and bipolar disorder.

In late May, ARIA plans to open a request for applications (RFA) for institutions to join the initiative’s Innovative Medicine and Precision Approaches to Clinical Trials (IMPACT) network, to perform clinical trials involving people who have profound autism, says Matthew State, ARIA’s scientific director and chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

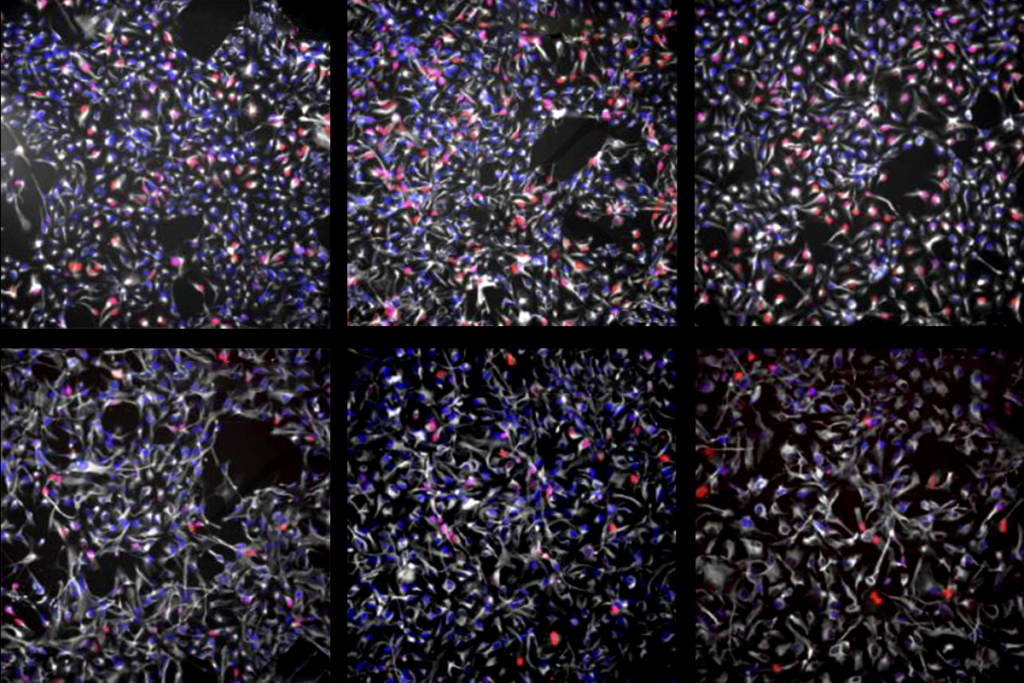

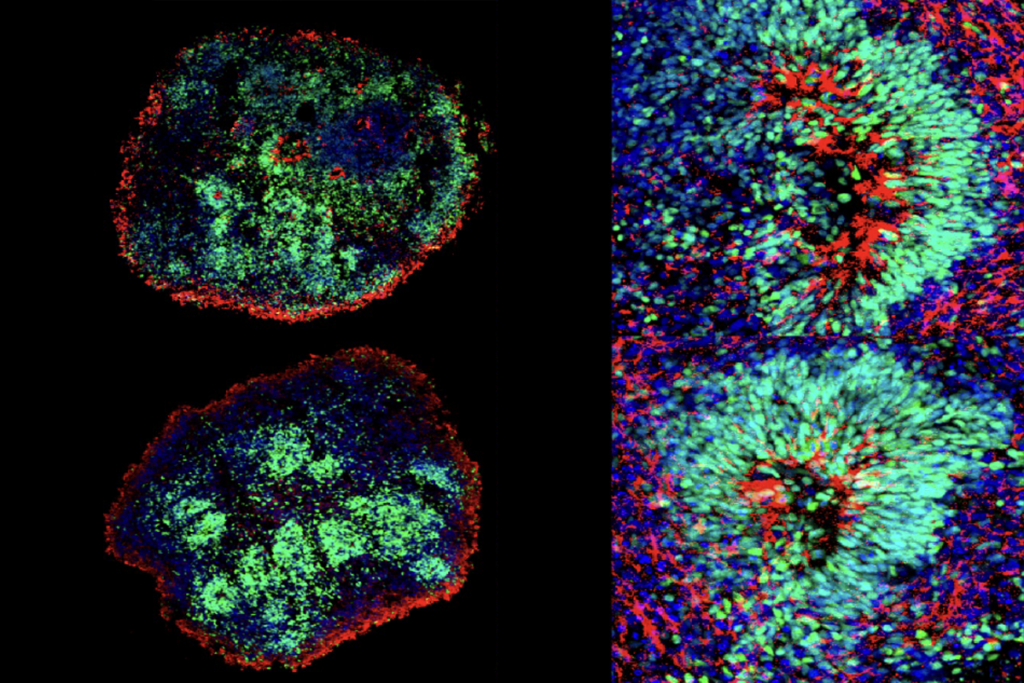

ARIA plans to invest in clinical infrastructure for these centers so that they can implement findings from basic and translational research carried out by “frontier science hubs,” State says, which will begin forming via an RFA later this year. The initiative seeks to develop diverse treatment modalities at these hubs, including genetic medicines, small molecules and neuromodulators. ARIA also intends to foster collaboration with researchers who work on conditions that overlap with autism, such as epilepsy and intellectual disability.

The focus areas reflect an assessment carried out by more than 150 researchers, patient advocates and other stakeholders on the current state of research and trials related to profound autism.

ARIA is led by State and the Coalition for Aligning Science, an organization that designs and implements biomedical research programs. State spoke with The Transmitter about ARIA’s approach to autism research and how it plans to speed up the path from basic science to clinical trials and treatments for profound autism.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: How does ARIA see itself in relation to existing efforts to support and spur autism research?

Matthew State: Our philosophy has been to work closely with families, with foundations and with other funders to make sure that this additional potential for investment is working in concert with what’s already going on.

One way we plan to do that is to organize a lot of activity around the clinical and translational space. There’s been nearly two decades of extraordinary progress in genetics and neurobiology, and a major push in open science. But we’ve identified that a coordinated effort intentionally linking that basic and translational science to clinical opportunities, including clinical trials, is quite important.

TT: How will the IMPACT network’s approach accelerate the development of therapies?

MS: At the 30,000-foot level, the notion is to create a dedicated clinical translational infrastructure at a national scale, bringing together basic and translational science with opportunities around clinical trials.

Let’s take the example of highly penetrant monogenic neurodevelopmental conditions. There’s the possibility of organizing efforts around nucleic acid targeting or genetic medicines. So we would want to have sites that can deliver that treatment and take care of kids who might be in those trials.

But they also need to have the capacity to partner closely with the existing family groups that are driving those kinds of trials. And we would want institutions to create multiscale, cross-biological-discipline, integrated research, with people who are working on a variety of scientific problems related to genetic medicines, and with a highly expert clinical infrastructure at the top of that.

That way, through the network as well as individual institutions, we would have the opportunity not only to deliver a therapy, but to work on the basic science behind that, such as model systems and delivery methodologies. We could also add quantitative behavioral phenotyping, so not only what the trial tells us about which approaches are efficacious, but how those trials can teach us about social development.

We aspire to build something akin to what began happening 50 or more years ago in pediatric cancer, where it became absolutely expected that when you went someplace, you not only had outstanding clinical care but also could engage in clinical trials or world-class research.

TT: Why the focus on profound autism?

MS: There are critically important challenges across the autism spectrum. Any decision to narrow that focus is not a statement about all of those other things. Ultimately, our ambition is to start where we are and have an impact across the spectrum.

For anyone who experiences autism as an impairment and is looking for clinical care, we think that one avenue to accelerate progress in the field is by focusing on profound autism. There are scientific reasons for this. Among people with profound autism, there is an enrichment for a number of things that are potentially tractable from a scientific standpoint—for example, the rate of de novo, highly penetrant variants that are pointing to specific genes.

So part of our strategy has been to leverage the incredible body of work elaborating the biology of those genes. It just gives opportunities for translation that many other conditions, and particularly adult-onset psychiatric disorders, do not have.

We think that’s very powerful for people with profound autism, in terms of thinking about near-term opportunities for treatment, but then also powerful for creating an environment that answers questions about the biology of language, social disability and overall cognitive functioning.

The second reason for focusing on profound autism is that it’s particularly challenging to engage these folks in research for practical reasons. As a consequence, when you look across the clinical translational space, this group and area of research is relatively underserved.

TT: Can you talk about ARIA’s plans to create a data-sharing infrastructure? Why is this an important aspect of ARIA?

MS: The goal is to complement, accelerate and promote progress. Creating a data infrastructure that helps support open science is absolutely essential to accomplishing that goal.

Even if all we were concerned about was making the IMPACT network operate at the highest level, then data integration and data management are absolutely crucial, not only within individual fields but to break down barriers that grow between fields because of different approaches to data management. When we find something interesting and worthwhile—a hypothesis that we’re able to test in a clinical trial—we don’t have to turn around and start again at square one in terms of data.

On top of that, the ambition is to make sure that what we learn empowers the entire field, and any field that is related and may have an interest in leveraging our data. That’s because we are also focused on aligning with areas that may not be defined by the core traits of autism but have really important overlap and are very meaningful for families and for patients, whether that’s epilepsy, severe intellectual disability, self-injurious behavior or sleep disturbances.

TT: Can you tell us about the invitation for IMPACT center applications that you have planned for late May? How many centers will be funded?

MS: There are a couple of working groups already that are getting close to having an RFA. One is led by Shafali Jeste at the University of Southern California and Mustafa Sahin at Boston Children’s Hospital.

We don’t have a limit on the number of IMPACT sites that will be funded over the course of the initiative, and we expect to roll out funding for sites in waves. In this initial wave, we are aiming for roughly 5 to 10 geographically dispersed sites led by transdisciplinary teams that work with patient and family groups and have experience caring for those on the severe end of the autism spectrum.

We then plan for a series of programs to be launched over the ensuing months focusing on both clinical trials as well as frontier science that will leverage this resource.

TT: What about future funding opportunities?

MS: We have multiple RFAs in development that will be launched once the initial IMPACT sites have been selected, tentatively by the end of the year. Among these are several focused on genetically defined cohorts and genetic medicines.

For example, one of the working groups developing an RFA is being led by Stephan Sanders at the University of Oxford and Tim Yu at Boston Children’s Hospital.

I don’t have any specific numbers at this point, but what I can tell you is that there’s a commitment on the part of the foundation to make sure that the funding matches the aspiration. We spent a lot of time thinking about “what would it take in order to build this?” and we feel confident that we’re at least in the ballpark.

TT: How will the funded teams incorporate family groups in their projects?

MS: Our intention is to advance scientific discovery and to create more therapeutic opportunities for those who seek treatment and support, and therefore their input will be invaluable to ensure that this “North Star” is always guiding us. These community voices will also be critical for day-to-day operations, including recruiting people interested in participating in research, informing clinical care for patients and ensuring successful outcomes.