The evolution of ‘autism’ as a diagnosis, explained

From a form of childhood schizophrenia to a spectrum of conditions, the characterization of autism in diagnostic manuals has a complicated history.

You can draw a straight line from the initial descriptions of many conditions – claustrophobia, for example, or vertigo – to their diagnostic criteria. Not so with autism. Its history has taken a less direct path with several detours, according to Jeffrey Baker, professor of pediatrics and history at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

Autism was originally described as a form of childhood schizophrenia and the result of cold parenting, then as a set of related developmental disorders, and finally as a spectrum condition with wide-ranging degrees of impairment. Along with these shifting views, its diagnostic criteria have changed as well.

Here is how the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM), the diagnostic manual used in the United States, has reflected our evolving understanding of autism.

Why was autism initially considered a psychiatric condition?

When Leo Kanner, an Austrian-American psychiatrist and physician, first described autism in 1943, he wrote about children with “extreme autistic aloneness,” “delayed echolalia” and an “anxiously obsessive desire for the maintenance of sameness.” He also noted that the children were often intelligent and some had extraordinary memory.

As a result, Kanner viewed autism as a profound emotional disturbance that does not affect cognition. In keeping with his perspective, the second edition of the DSM, the DSM-II, published in 1968, defined autism as a psychiatric condition — a form of childhood schizophrenia marked by a detachment from reality. During the 1950s and 1960s, autism was thought to be rooted in cold and unemotional mothers, whom Bruno Bettelheim dubbed ‘refrigerator mothers.’

When was autism recognized as a developmental disorder?

The ‘refrigerator mother’ concept was disproved in the 1960s to 1970s, as a growing body of research showed that autism has biological underpinnings and is rooted in brain development. The DSM-III, published in 1980, established autism as its own separate diagnosis and described it as a “pervasive developmental disorder” distinct from schizophrenia.

Prior versions of the manual left many aspects of the diagnostic process open to clinicians’ observations and interpretations, but the DSM-III listed specific criteria required for a diagnosis. It defined three essential features of autism: a lack of interest in people, severe impairments in communication and bizarre responses to the environment, all developing in the first 30 months of life.

How long did this definition last?

The DSM-III was revised in 1987, significantly altering the autism criteria. It broadened the concept of autism by adding a diagnosis at the mild end of the spectrum — pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) — and dropping the requirement for onset before 30 months.

Even though the manual did not use the word ‘spectrum,’ the change reflected the growing understanding among researchers that autism is not a single condition but rather a spectrum of conditions that can present throughout life.

The updated manual listed 16 criteria across the three previously established domains, 8 of which had to be met for a diagnosis. Adding PDD-NOS allowed clinicians to include children who didn’t fully meet the criteria for autism but still required developmental or behavioral support.

When was autism first presented as a spectrum of conditions?

The DSM-IV, released in 1994 and revised in 2000, was the first edition to categorize autism as a spectrum.

This version listed five conditions with distinct features. In addition to autism and PDD-NOS, it added ‘Asperger’s disorder,’ also at the mild end of the spectrum; ‘childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD),’ characterized by severe developmental reversals and regressions; and Rett syndrome, affecting movement and communication, primarily in girls. The breakdown echoed the research hypothesis at the time that autism is rooted in genetics, and that each category would ultimately be linked to a set of specific problems and treatments.

Why did the DSM-5 adopt the idea of a continuous spectrum?

Throughout the 1990s, researchers hoped to identify genes that contribute to autism. After the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, many studies tried to zero in on a list of ‘autism genes.’ They found hundreds, but could not link any exclusively to autism. It became clear that finding genetic underpinnings and corresponding treatments for the five conditions specified in the DSM-IV wouldn’t be possible. Experts decided it would be best to characterize autism as an all-inclusive diagnosis, ranging from mild to severe.

At the same time, there was growing concern about a lack of consistency in how clinicians in different states and clinics arrived at a diagnosis of autism, Asperger syndrome or PDD-NOS. A spike in autism prevalence in the 2000s suggested that clinicians were sometimes swayed by parents lobbying for a particular diagnosis or influenced by the services available within their state.

To address both concerns, the DSM-5 introduced the term ‘autism spectrum disorder.’ This diagnosis is characterized by two groups of features: “persistent impairment in reciprocal social communication and social interaction” and “restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior,” both present in early childhood. Each group includes specific behaviors, a certain number of which clinicians have to identify. The manual eliminated Asperger syndrome, PDD-NOS and classic autism, but debuted a diagnosis of social communication disorder to include children with only language and social impairments. Childhood disintegrative disorder and Rett syndrome were removed from the autism category.

Why did the DSM-5 spawn so much concern and controversy?

Even before the manual was released in 2013, many people with autism and their caregivers worried about its effect on their lives. Many were concerned that after their diagnosis disappeared from the book, they would lose services or insurance coverage. Those who identified themselves as having Asperger syndrome said the diagnosis gave them a sense of belonging and an explanation for their challenges; they feared that removing the diagnosis was synonymous to losing their identity. And experts disagreed on whether the DSM-5’s more stringent diagnostic criteria would block services for those with milder traits or adequately curb surging prevalence rates.

Five years later, it’s clear the DSM-5 did not cut services for people already diagnosed with an autism spectrum condition. A growing body of evidence, however, shows that its criteria do exclude more people with milder traits, girls and older individuals than the DSM-IV did.

Are there alternatives to the DSM?

Clinicians in many countries, including the United Kingdom, use the International Classification of Diseases. Released in the 1990s, that manual’s current and 10th edition groups autism, Asperger syndrome, Rett syndrome, CDD and PDD-NOS together in a single ‘Pervasive Developmental Disorders’ section, much as the DSM-IV did.

What does the future look like for diagnosing autism?

Experts continue to view autism as a continuous spectrum of conditions. There are no planned revisions to the DSM for now, but the language in a draft of the ICD-11 — which is expected to debut in May 2018 — mirrors the DSM-5’s criteria. In the ICD-11, autism criteria move to a new, dedicated ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder’ section.

The ICD-11 differs from the DSM-5 in several key ways. Instead of requiring a set number or combination of features for a diagnosis, it lists identifying features and lets clinicans decide whether an individual’s traits match up. Because the ICD is intended for global use, it also sets broader, less culturally specific criteria than the DSM-5 does. For instance, it puts less emphasis on what games children play than whether they follow or impose strict rules on those games. The ICD-11 also makes a distinction between autism with and without intellectual disability, and highlights the fact that older individuals and women sometimes mask their autism traits.

Corrections

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the publication date for the DSM-II.

Syndication

This article was republished in Science.

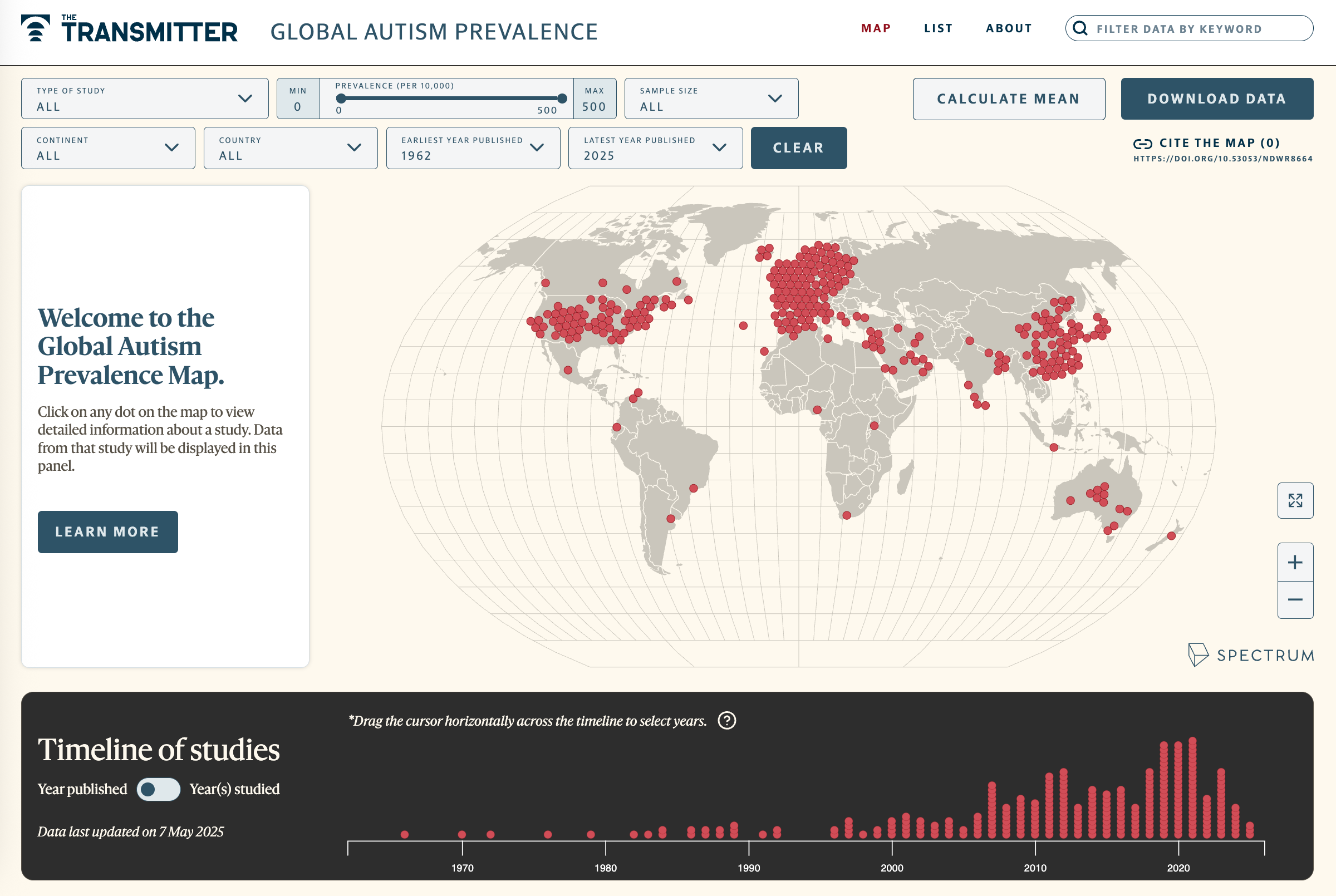

Visit our Global Autism Prevalence Map

Explore more >

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Autism prevalence increasing in children, adults, according to electronic medical records

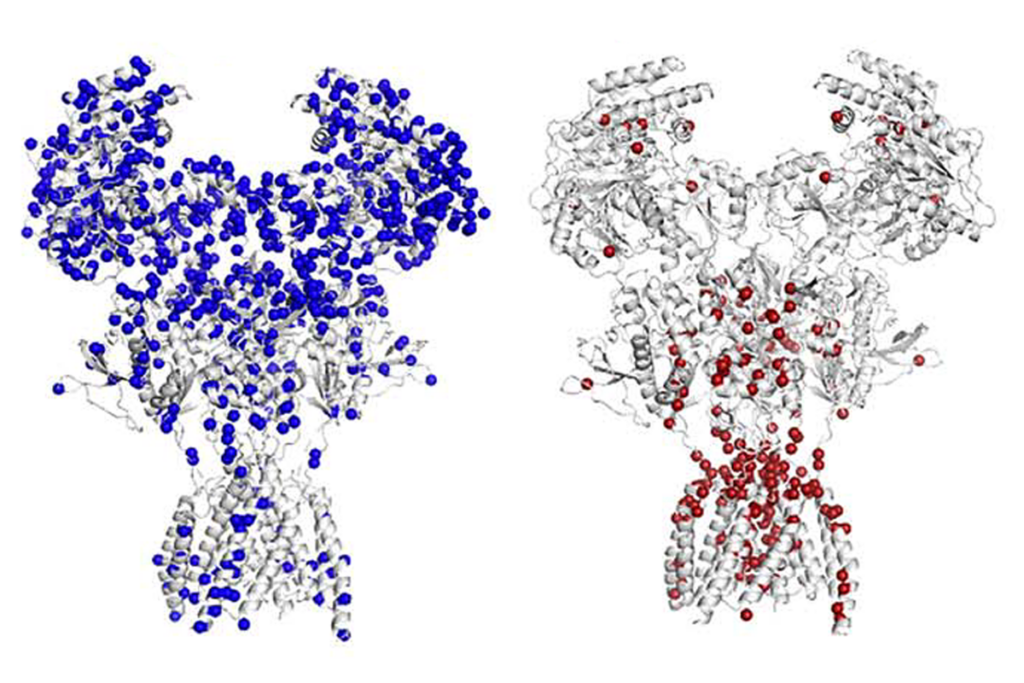

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism