If a person thinks they might have autism, they will usually see their general practitioner as the first port of call. The general practitioner will use a screening test to help them decide if the person should be referred to a specialist for a formal diagnosis.![]()

However, we recently discovered, by chance, an error in the clinical guidelines clinicians use when making their initial autism assessment. That guideline is published by the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and it also informs clinical guidelines internationally.

The guideline on autism recommends that clinicians use the autism spectrum quotient (AQ10) to measure autism traits. The AQ10 contains 10 statements about autism traits, such as “I find it difficult to work out people’s intentions,” which reflects research showing that autistic people find it difficult to understand what other people are thinking. The maximum score is 10, and higher scores represent more autism traits.

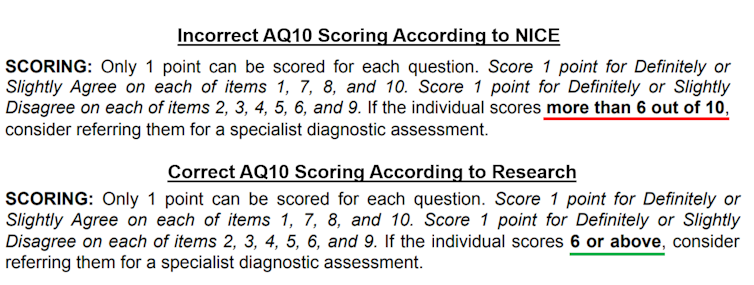

NICE recommends that people who score 7 or more should be referred for a full diagnostic assessment by their doctors, but the correct value should be 6 or more. NICE examined the suitability of the AQ10 based on research in 2012 showing that a value of 6 or more was optimal, but the final guidance appears to be incorrectly published with the ‘7 or more’ recommendation.

A score of 6 or more is the optimal screening value because this makes the AQ10 sensitive enough to help identify autistic adults but also specific enough to help rule out people without autism.

The difference between 6 and 7 might not seem large, but a one-point difference on a test with only 10 statements has a big impact. The incorrect 7 or more cutoff recommended by NICE makes the AQ10 far less sensitive. This is because many people who score 6 are likely to be autistic but may not have been referred for clinical assessments as needed.

Autism diagnoses may have been delayed as a result, and some people may not have been diagnosed at all. Many people will not have received the correct support at the right time and are likely to have experienced additional mental health difficulties, such as anxiety, which commonly accompany autism.

At sixes and sevens:

To make matters worse, the NICE guidelines have been in place since 2012, so incorrect autism screening has been occurring for almost a decade. Many researchers have also used the incorrect NICE guidance, for example, by incorrectly recruiting study participants based on their AQ10 scores.

It is impossible to put a number on how many autism diagnoses have been affected by the incorrect NICE guidance. By highlighting this error, we hope to enhance the discussions people have with their doctors, rather than undermine this important relationship.

We have now informed NICE about the issue — they have yet to reply, and their guidance needs to be reviewed. Until then, doctors and researchers should use the correct 6 or more cut-off score, in line with the original research.

Several new autistic personality trait tests are emerging, creating a better future for understanding autism. They include a shortened version of the AQ10 and a test that uses a different scoring method.

There have also been improvements in detecting the signs of autism in children, as well as using films rather than surveys to guide clinicians. Although these developments have yet to work their way into the NICE guidelines, they will improve autism screening, diagnosis, and research in the coming years.![]()

This story is republished from The Conversation. It has been slightly modified to reflect Spectrum’s style.