Epigenetic age

Normal aging triggers dramatic changes to the epigenome, the set of chemical tags that turn genes on and off, according to a new study.

Our DNA code is fixed: For better or for worse, we keep whatever we’re born with. So it’s easy to forget that genetic information actually changes all the time.

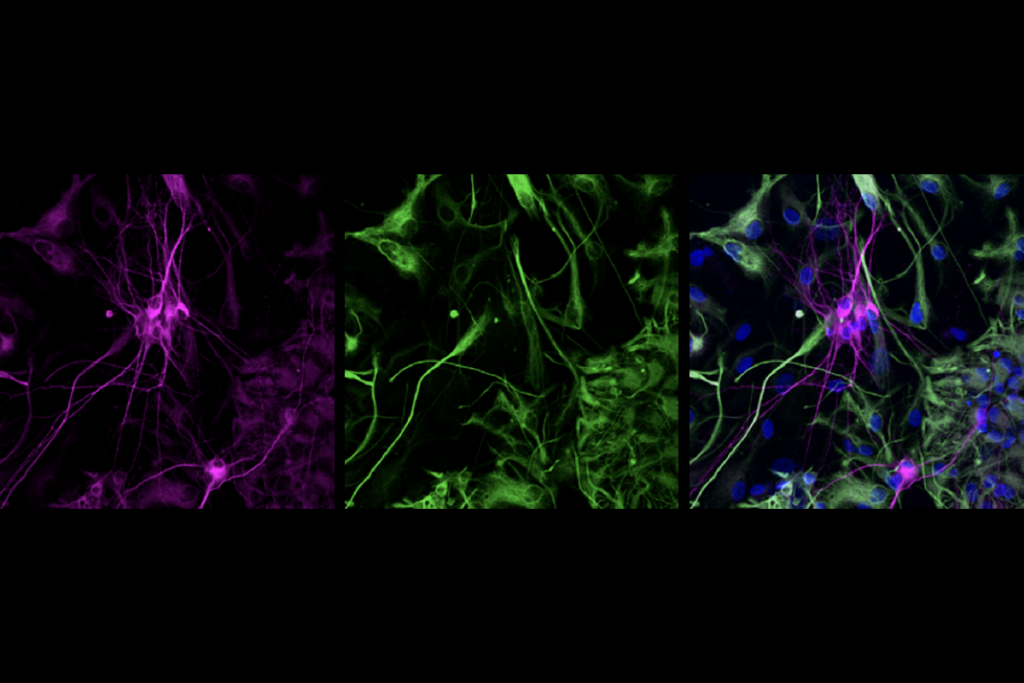

That’s largely because of the epigenome — the set of chemical tags on DNA that turn gene expression on and off. Glitches in this extra layer of the genome have been linked to all sorts of disorders, including autism.

Epigenetic markers can be influenced by chemical exposures in the environment, diet, hormones and even the firing patterns of neurons. A study published 11 June in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that normal aging, too, ushers in dramatic epigenetic changes.

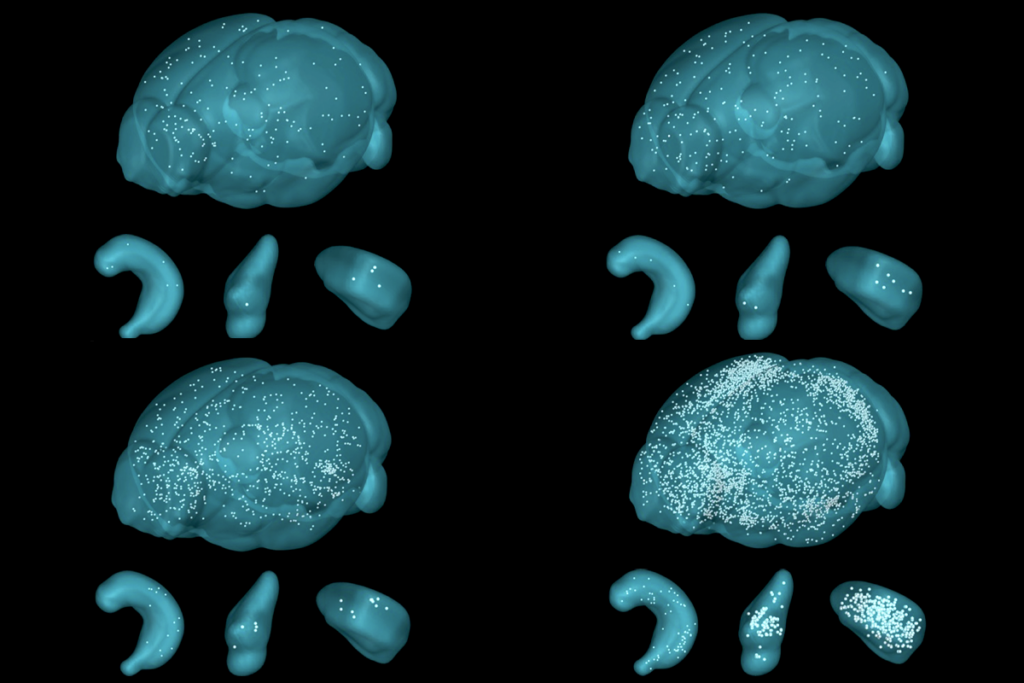

The researchers focused on a common type of epigenetic regulation in which a methyl group attaches to a DNA letter, typically cytosine. Comparing white blood cells from a newborn baby, a 26-year-old and a 103-year-old, the scientists found that methylation decreases with age.

The baby’s genome is 80 percent methylated, compared with 78 percent in the young adult and 73 percent in the centenarian. The trend held up when the team increased the sample to 19 newborns and 19 people aged 89 to 100.

Researchers don’t know yet how or why these changes happen. For instance, they could be related to the loss with age of enzymes called DNA methyltransferases that help attach the methyl groups to DNA. Diet could also be a big factor. Folate, a B vitamin that we absorb from food, is necessary for DNA synthesis and methylation.

The researchers focus on the implications of their data for understanding the aging process — does the slow loss of methylation contribute to the general decline in our health over time? But the difference between the baby and the 26-year-old hints that epigenetics is important early in life as well as at the end of the lifespan.

Certain genes related to methyltransferases have been tied to autism, and a few research groups have reported abnormally low levels of folate in children with the disorder. For now, though, we can only guess at the mechanisms involved.

Two groups are charting methylation patterns in the blood of pregnant women who already have one child with autism. To fill in the many missing links, more studies need to probe the epigenome of individuals with autism, at every age.

Recommended reading

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky