Encouraging speech

Little evidence supports the use of sign language for nonverbal children with autism, but other therapies show promise, says a review published 24 April in Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience.

About 25 percent of children with autism are nonverbal. Yet there is a lack of rigorous studies measuring the effectiveness of different therapies for these children, says a review published 24 April in Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience.

Sign language, one of the more common therapies, may work in conjunction with other approaches for children who have some verbal skills, but it does not improve speech in most nonverbal children with autism, according to the review.

What’s more, children who have autism and impaired motor skills often have difficulty signing and struggle with imitation and symbolic representation.

That message has eluded clinicians: A survey of specialists from 69 school districts in California found that many consider sign language training an effective intervention for autism.

Another commonly used autism therapy, the picture exchange communication system (PECS), seems better able to improve language abilities, imitation and joint attention — following the gaze of another — in nonverbal children with autism. Unlike sign language, PECS does not require fine motor skills.

Researchers compared PECS with Responsive Education and Prelinguistic Milieu Teaching, a therapy with two components: showing parents how to play with their children in ways that encourage language development, and teaching children gestures, joint attention and speech through play.

Compared with this method, PECS is more successful at helping nonverbal children with autism increase their frequency and range of spoken words after six months of treatment.

Multiple studies also show encouraging results from the Early Start Denver Model, a play-based therapy. This approach improves language and behavioral skills, and encompasses reciprocal imitation training, which improves imitation, pretend play, language and joint attention skills, according to a small study.

Three other therapies — prompts for restructuring oral muscular phonetic targets, auditory-motor mapping treatment and electromagnetic brain stimulation — have each been assessed in a single study of nonverbal children with autism. More research is needed to measure their effectiveness, the researchers say.

Interventions that have targeted children younger than 5 years old yield better speech and language improvements than those aimed at older children, the new study found.

Perhaps the greatest need is to identify behaviors that put children with autism at risk for speech delays. This information could be used to develop more effective therapies, the researchers say.

For example, children often miss important motor milestones, such as banging on toys with their hands and imitating other people’s gestures and facial expressions. Research suggests that early motor behavior may be associated with language development.

Recommended reading

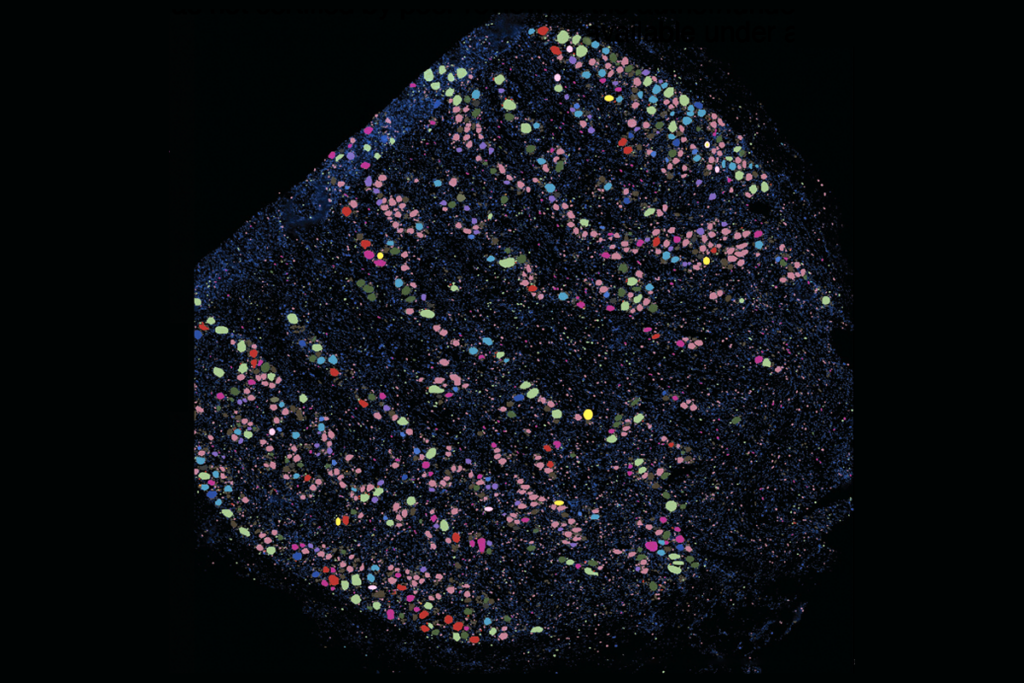

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models