Empowering plan; autism army; mustache mismatch

Hillary Clinton makes history with her autism plan, an Israeli army unit seeks soldiers on the spectrum, and there are more mustachioed medical department heads than female ones.

- Hillary Clinton has made political history by unveiling an autism plan as part of her presidential bid. The plan, released Tuesday, is getting kudos from autism advocates for focusing on services for people on the spectrum rather than cures for a ‘disease.’

“If she wins the election and does even half of the things she promises, she could make an enormous difference in the everyday lives of autistic people,” disability advocate Sara Luterman wrote in an op-ed for The Guardian.

Part of the plan aims to improve the lives of adults with autism by assessing their needs and helping them to secure jobs and housing.

“As a left-leaning 20-something, I would have never predicted that I would use the word ‘delighted’ in relation to Hillary Clinton,” Luterman wrote, referring to Clinton’s “relatively conservative” views. “However, in promising to help support and preserve the rights of people whose humanity is rarely acknowledged, she has proposed something more progressive than many, if not all, of her opponents’ policies.”

- An Israeli army unit tasked with scanning satellite images for suspicious activity employs dozens of soldiers on the spectrum, according to a story published this week in The Atlantic.

The story focuses on a 21-year-old soldier in the Israel Defense Force’s Visual Intelligence Division, dubbed Unit 9900. The man, called “E.” to protect his identity, struggled in school but feels at home within the rigid structure of the army.

“For these young people, the unit is an opportunity to participate in a part of Israeli life that might otherwise be closed to them,” the story reads. “And for the military, it’s an opportunity to harness the unique skill sets that often come with autism: extraordinary capacities for visual thinking and attention to detail, both of which lend themselves well to the highly specialized task of aerial analysis.”

- Wednesday marked the last day for public comment on a proposed overhaul to the ‘common rule’ — a decades-old set of ethical protections for research participants. The revamped regulations would extend these protections to biological specimens, requiring researchers to obtain informed consent for the use of these precious samples or purge them.

Rebecca Skloot, author of “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” says the overhaul is essential for preserving public trust in science. Her book reveals how cancer cells taken without consent from a poor, black woman became one of the most widely used research tools to date.

“People have told me by the thousands, and numerous public opinion studies find the same: They want to know if their biospecimens are used in research, and they want to be asked first,” Skloot wrote in an op-ed in last week’s New York Times. “Most will probably say yes, because they understand it’s important. They just don’t want to find out later. That damages their trust in science and doctors.”

- Researchers routinely report when people drop out of research studies. But with mice, it’s a different story.

A new study published this week in PLOS Biology suggests that up to one-third of mouse studies omit some mice from their final analysis, but few explain why. If researchers are leaving out some mice for, say, being statistical outliers, they could drastically overstate the effectiveness of a particular treatment, according to the study.

The paper could help to explain why some 80 percent of drugs that look promising in animals have no benefit in people. It also includes an homage, with apologies, to Pete Seeger:

Where have all the rodents gone?

Ooh ooh, ooh ooh, ooh

To non-random attrition, every one

When will they ever learn? - The British Medical Journal is famous for its silly holiday issue. But one study in the 2015 lineup is no laughing matter.

The study compares the number of “moustachioed” department heads at major U.S. medical schools with the number of women in those same leadership roles.

“We chose to study moustaches as the comparator because they are rare (<15 percent of men from the most recent measures available), and we wanted to learn if women were even rarer,” the researchers write.

They found that 137 out of 1,018 department heads at 50 top medical schools are women (13 percent) and 190 department heads are mustachioed (19 percent). The overall “moustache index” — the ratio of female department heads to mustachioed ones — is 0.72.

“We believe that every department and institution should strive for a moustache index ≥1,” the researchers write.

Recommended reading

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

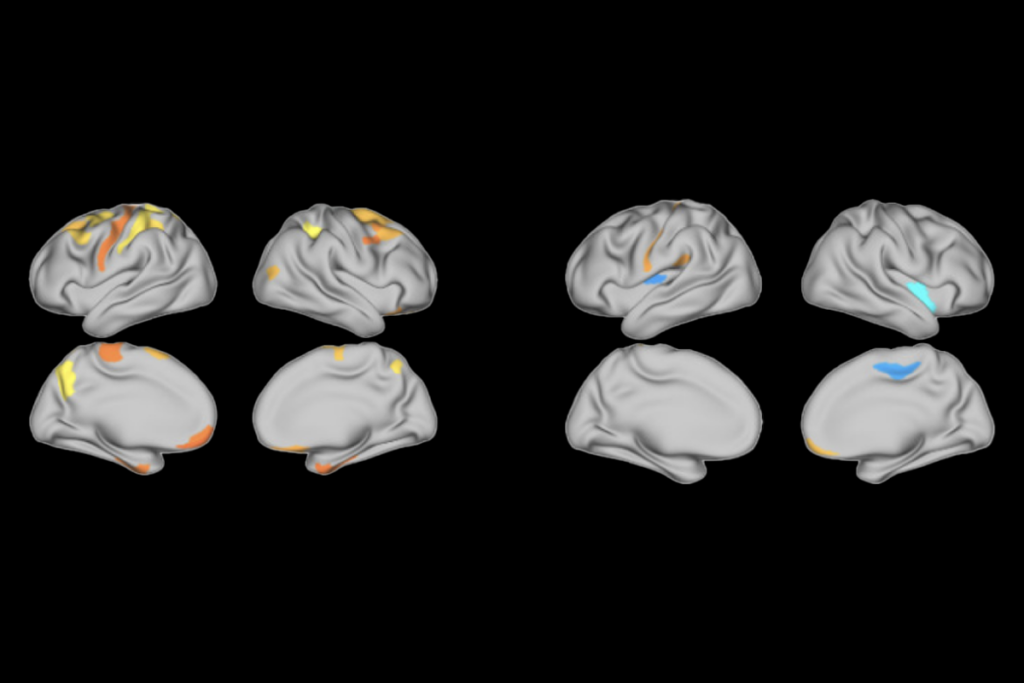

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

FDA website no longer warns against bogus autism therapies, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Betting blind on AI and the scientific mind