Emergency rooms see surge of teenagers seeking psychiatric care

Emergency rooms throughout California are reporting a sharp increase in adolescents and young adults seeking care for a mental health crisis.

Less than a decade ago, the emergency department at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, California, would see maybe one or two young people per day, says Benjamin Maxwell, the hospital’s interim director of child and adolescent psychiatry.

Now it’s not unusual for the emergency room to see 10 adolescents and young adults in a day, and sometimes even 20, Maxwell says. “What a lot of times is happening now is kids aren’t getting the care they need, until it gets to the point where it is dangerous,” he says.

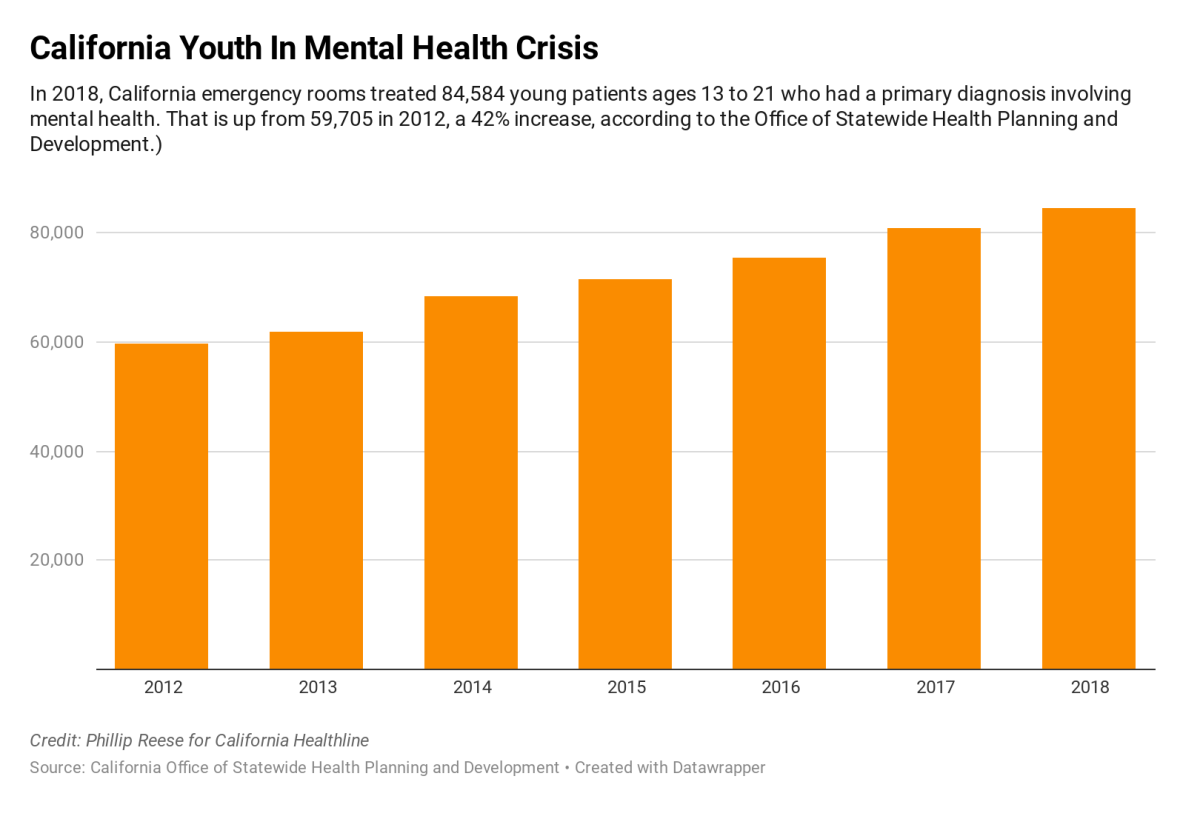

ERs throughout California are reporting a sharp increase in adolescents and young adults seeking care for a mental health crisis. In 2018, California ERs treated 84,584 individuals ages 13 to 21 who had a primary diagnosis involving mental health. That is up from 59,705 in 2012, a 42 percent increase, according to data provided by the California of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

By comparison, the number of ER encounters among that age group for all other diagnoses grew by just 4 percent during the same period. And the number of ER encounters involving mental health among all other age groups — everyone except adolescents and young adults — rose by about 18 percent.

The spike in youth mental health visits corresponds with a recent survey that found that members of ‘Generation Z’ — defined in the survey as people born since 1997 — are more likely than other generations to report their mental health as fair or poor. The 2018 polling, done on behalf of the American Psychological Association, also found that members of Generation Z, along with millennials, are more likely to report receiving treatment for mental health issues.

The trend corresponds with another alarming development as well: a marked increase in suicides among teenagers and young adults. About 7.5 of every 100,000 young people aged 13 to 21 in California died by suicide in 2017, up from a rate of 4.9 per 100,000 in 2008, according to the latest figures from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationwide, suicides in that age range rose from 7.2 to 11.3 per 100,000 from 2008 to 2017.

Disconnected and bullied:

Researchers are studying the causes of the surging reports of mental distress among America’s young people. Many recent theories note that the trend parallels the rise of social media, an ever-present window on peer activities that can exacerbate adolescent insecurities and open new avenues for bullying.

“Even though this generation has been raised with social media, youth are feeling more disconnected, judged, bullied and pressured from their peers,” says Susan Coats, a school psychologist at Baldwin Park Unified School District near Los Angeles.

“Social media: It’s a blessing and it’s a curse,” Coats says. “Social media has brought youth together in a forum where maybe they may have felt isolated before, but it also has undermined interpersonal relationships.”

Members of Generation Z also report significant levels of stress about personal debt, housing instability and hunger, as well as mass shootings and climate change, according to the American Psychological Association survey.

Resources to prevent mental health crises among youth are often lacking.

“We’re not doing a great job with … catching things before they devolve into broader problems, and we’re not doing a good job with prevention,” says Lishaun Francis, associate director of health collaborations at Children Now, an Oakland, California-based nonprofit.

Struggling to keep up:

Many California school districts don’t have enough school psychologists and don’t devote enough resources to teaching students how to cope with depression, anxiety and other mental health issues, says Coats, who chairs the mental health and crisis consultation committee of the California Association of School Psychologists.

In the broader community, medical providers also are struggling to keep up. “Many times there aren’t psychiatric beds available for kids in our community,” Maxwell says.

Most of the adolescents who come into the emergency room at Rady Children’s Hospital during a mental health crisis are considering suicide, have attempted suicide or have harmed themselves, says Maxwell, who is also the hospital’s medical director of inpatient psychiatry.

These individuals are triaged and quickly seen by a social worker. Often, a behavioral health assistant is assigned to sit with the young people throughout their stay.

“Suicidal patients — we don’t want them to be alone at all in a busy emergency department,” Maxwell says. “So that’s a major staffing increase.”

Rady Children’s Hospital plans to open a six-bed, 24-hour psychiatric emergency department in 2020. Improving emergency care will help, Maxwell says, but a better solution would be to intervene with young people before they need an ER.

“The ED surge probably represents a failure of the system at large,” Maxwell says. “They’re ending up in the emergency department because they’re not getting the care they need, when they need it.”

This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News. It has been slightly modified to reflect Spectrum‘s style.

Recommended reading

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Molecular changes after MECP2 loss may drive Rett syndrome traits

Explore more from The Transmitter

Organoids and assembloids offer a new window into human brain

Who funds your basic neuroscience research? Help The Transmitter compile a list of funding sources