Elliott Sherr: Coaching teams to tackle autism’s mysteries

Elliott Sherr is unraveling the effects of genetics and brain structure in a handful of disparate disorders that each illuminates some aspect of autism.

At first glance, you wouldn’t peg Elliott Sherr as a basketball player — he’s not particularly tall or lanky. But basketball has been his sport ever since he was a schoolboy in southern California. More recently, he coached his three children’s community basketball league teams for nine years.

Sherr hung up his coach’s whistle last year (his children are all old enough to play on school teams now). When he looks back on his experience as a coach, he takes particular pride in games in which every member of the team scored.

That inclusive yet disciplined approach also translates to his lab at the University of California, San Francisco, where Sherr is a child neurologist and geneticist.

Rather than focus on just one disorder, his lab is trying to unravel the effects of genetics and brain structure in a handful of disparate disorders that each illuminate some aspect of autism. He is among only a few autism researchers who evaluate children with autism in the clinic.

He is also probing changes in brain wiring that may be akin to those present in autism, working out how autism symptoms can derive from either duplications or deletions of the same genes, and characterizing animal models of the disorder.“Being overcommitted is one of my flaws,” he says.

Sherr lets the self-deprecating joke hang there for a long beat. His sense of humor is so dry, colleagues say they can’t always tell whether he’s joking.

Sherr has good reason for having so many irons in his scientific fire, however.

“There are probably two main hypotheses that are out there about autism so far,” he says. “One is that autism is a disruption in neuronal connectivity, and the other is that autism is an imbalance of excitation and inhibition.”

Two of Sherr’s primary research interests, the corpus callosum and epilepsy, directly address these two hypotheses.

Dual focus:

The corpus callosum is the thick bundle of nerve fibers that connects the two hemispheres of the brain. People born without this structure often have social deficits, and Sherr and his colleagues have found that 45 percent of children with this defect, known as agenesis of the corpus callosum (AgCC), meet the criteria for autism1.

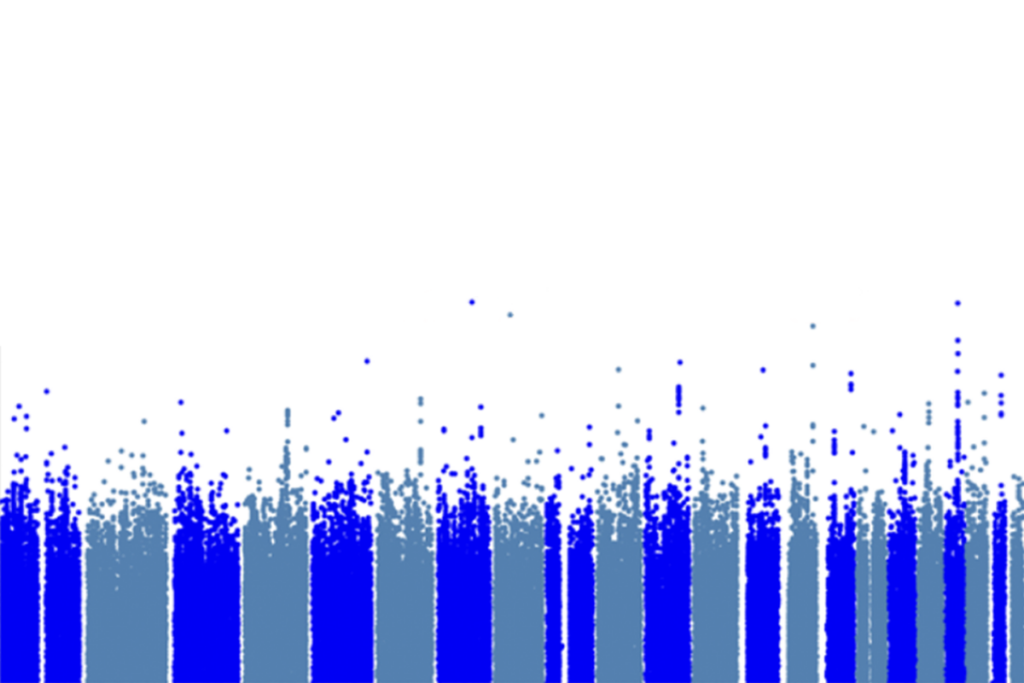

The connectivity theory of autism holds that people with autism have defective long-range connections in the brain. Lacking a corpus callosum is an extreme example of having impaired long-range connections, Sherr notes. He and his collaborators have shown that the absence of a corpus callosum results in a broad rewiring of the brain’s structural connections2.

Sherr has also helped to suss out genomic regions associated with the birth defect3.

“That’s a small field where he’s made really seminal contributions,” says Elysa Marco, assistant professor of clinical neurology at the University of California, San Francisco and a former student and longtime collaborator.

“I’ve learned more by seeing families in a more natural setting than in a very formalized setting inside of a clinic.”

Sherr and his colleagues assembled a group of 374 individuals who were born without the brain structure, including 100 who had never been studied before. They identified 12 areas of the genome associated with the defect, as well as overlaps with genetic causes of other brain malformations.

Sherr also studies the genetics of epilepsy, a condition in which surges of excitatory nerve impulses in the brain cause seizures. Epilepsy affects about 30 percent of people with autism, and some researchers believe that a less extreme imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory nerve impulses underlies autism itself.

Some researchers might pick a favorite theory about autism up front and look for evidence to support it, but Sherr’s work explores both views of autism.

He shows a similar open-mindedness in the clinic, says Marco, who first met Sherr when she was a medical student and he was completing a child neurology fellowship. Sherr still sees patients at the university’s Benioff Children’s Hospital, mostly children with severe epilepsy or brain malformation.

“We would be on rounds, and it wouldn’t be unusual to take a 15-minute interlude to check out some articles about a subject so that we could make a really well-founded decision,” Marco recalls. In other words, he didn’t need to have all the answers. “He’s got a humble approach.”

Reaching out:

Since the earliest days of his career, Sherr has been unafraid of what he doesn’t know.

“In his thesis work, Elliott took on a project on which neither he nor I had much background or familiarity with the required methodologies,” says Lloyd Greene, professor of pathology and cell biology at Columbia University in New York, and Sherr’s Ph.D. adviser. “Elliott proceeded to master the subject and the methodologies largely on his own.”

Greene’s lab focused mainly on neuronal differentiation, but for his dissertation, Sherr sequenced the genes for a family of small myosins, molecular motors related to the proteins involved in muscle contraction, and mapped their expression in the mouse brain4.

Overcommitted from the beginning, Sherr was part of an M.D./Ph.D. program. “I got interested in autism and intellectual disability through my work as a clinician,” he says.

He says he hoped that studying the biology underlying these conditions might not only help people with disorders, but also yield broader insights into why people think and behave the way they do. To learn more, hebegan to get involved with family support groups for rare neurodevelopmental disorders.

“In some ways, I’ve learned more by seeing families that way, in a more natural setting, than in a very formalized setting inside of a clinic room,” Sherr says.

The goodwill and rapport he developed this way are also key to the success of his research. “He’s able to attract relatively large numbers of people so that they will come from across the country or even other countries to be involved in these studies,” says Pratik Mukherjee, associate professor of radiology at the University of California, San Francisco, who collaborates with Sherr on brain imaging studies of AgCC and other conditions.

Most recently, Sherr has gotten to know families of children with deletions or duplications of a chromosomal region called 16p11.2. These genetic defects increase the risk for autism and are the subject of the Simons Variation in Individuals Project, which is funded by SFARI.org’s parent organization.

Together with a consortium of European researchers, the project has reported that carriers of the deletion have lower intelligence quotients than unaffected relatives, and 15 percent also have autism5.

Of course, teasing out the relationships between autism symptoms and genetics isn’t always straightforward. A study in Sherr’s lab of BTBR mice, which lack a corpus callosum and show autism-like behaviors, failed to find a genetic link between these two conditions6.

Sherr says the experience spurred him to look beyond mouse models of autism. He is now part of a team working to develop a monkey model of the disorder. “I think I was more sanguine about being able to use mice earlier on than I am now,” he says.

This constantly expanding set of research questions and methodologies also requires an equally diverse set of collaborators — something that plays to Sherr’s strengths.

“He’s a really good team player,” says Karen Parker, assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford University in California, and a collaborator. “He’s very good at including everyone — I like how he treats everyone on the team, from technicians to postdocs.”

References:

1:Lau Y.C. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 1106-1118 (2013) PubMed

2: Owen J.P. et al. Neuroimage 70, 340-355 (2013) PubMed

3: O’Driscoll M.C. et al. Am. J. Med Genet. A.152A, 2145-2159 (2010) PubMed

4: Sherr E.H. et al. J. Cell Biol. 120, 1405-1416 (1993) PubMed

5: Zufferey F. et al. J. Med. Genet. 49, 660-668 (2012) PubMed

6: Jones-Davis D.M. et al. PLoS ONE 8, e61829 (2013) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects