Early seizures linked to severe form of tuberous sclerosis

Children with tuberous sclerosis who have seizures as infants are particularly likely to also have developmental delay and autism features.

Children with tuberous sclerosis who have seizures as infants are particularly likely to also have developmental delay and autism features, according to a new study1.

The study gets at an important question in autism research, although it stops short of answering it conclusively: whether having seizures in infancy directly contributes to a poor outcome later.

Children in the study who have seizures before age 1 show the worst outcome, based on tests of cognitive ability.

“This is one of the most methodologically rigorous demonstrations of the association of early-life seizures in tuberous sclerosis with intellectual disability,” says Orrin Devinsky, director of the New York University Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, who was not involved in the study.

Tuberous sclerosis is a genetic condition characterized by benign tumors throughout the brain and body. Doctors can diagnose it before birth by detecting the tumors on an ultrasound. Roughly half of children with the syndrome also have autism, and 80 to 90 percent develop epilepsy.

The findings hint that preventing seizures early in children with tuberous sclerosis could lessen the severity of their condition, says co-lead investigator Jamie Capal, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio. “If we target interventions prior to 12 months, then these kids are going to have a much better developmental outcome.”

Forward look:

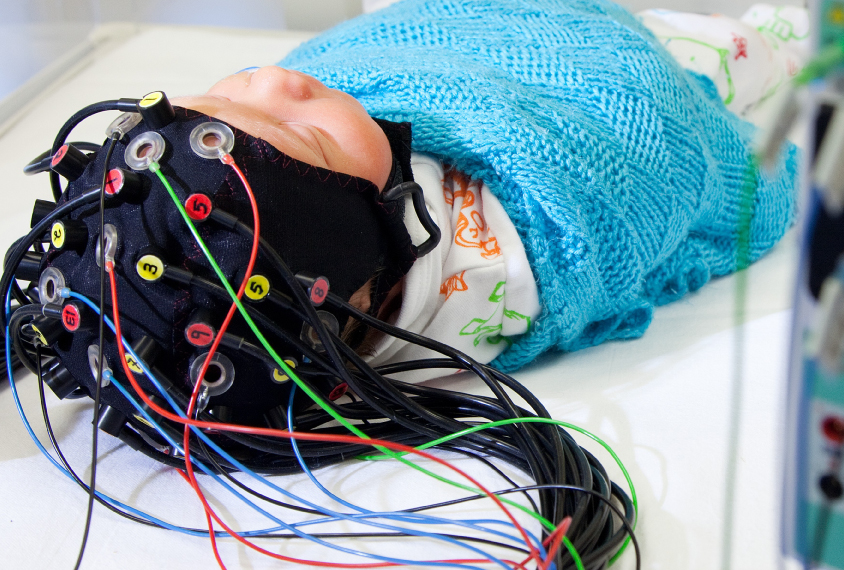

Capal and her colleagues followed 130 children with tuberous sclerosis from 3 months to 2 years of age. Every three to six months, they assessed the children’s cognitive ability, daily living skills and language. Clinicians screened the children for signs of autism at age 1 and assessed them using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale at age 2.

The researchers also scanned the children’s brains at each visit for the presence of structural abnormalities.

“The design of this study is really powerful,” says Sarah Spence, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved. “It gives us really good information about which are the kids with tuberous sclerosis who are going on to develop the significant cognitive impairment and the autism symptoms.”

Onset of seizures before age 1 is a bigger predictor of a poor outcome, including autism features, than either the frequency or type of seizures, the researchers found. (It is as yet unclear whether seizures predict autism, because the children are 2, an age at which autism cannot reliably be diagnosed.) The 35 children who had no history of seizures showed no signs of developmental delay at age 2. The results were published in the May issue of Epilepsy and Behavior.

Common cause:

The study does not prove that seizures cause autism or intellectual disability. Instead, the seizures may merely signal a more severe form of the condition. Clinical data suggest that either scenario might be true, Devinsky says.

Other data from the ongoing study may help resolve this uncertainty, says co-lead investigator Mustafa Sahin, professor of neurology at the Harvard University.

The researchers are trying to determine whether specific alterations in brain structure predict seizures, intellectual disability or autism in the children. If these problems all track with the same brain feature, then they may stem from a common biological cause, Sahin says.

The team is planning a clinical trial to see whether preventing seizures with medication improves outcomes in children with tuberous sclerosis. Researchers plan to administer the treatment to babies whose brains show signs of seizures before the first seizure appears.

References:

- Capal J.K. et al. Epilepsy Behav. 70, 245-252 (2017) PubMed

Recommended reading

Explore more from The Transmitter

Some facial expressions are less reflexive than previously thought