Early activity of brain’s emotion hub may yield clues to autism

The brain’s emotion center, the amygdala, undergoes dramatic changes during the first year of life; these shifts may hold hints about its role in autism.

The brain’s emotion center, the amygdala, undergoes dramatic changes during the first year of life, new research suggests1. These shifts may hold hints about the region’s role in autism.

In the first several weeks after birth, the amygdala and sensory regions are functionally connected — meaning they frequently work together — according to the study. But the connections mostly disappear by a baby’s first birthday. By then, the amygdala has formed connections that resemble those in adults.

“This first year of life is just so important for laying out the fundamental architecture of how the brain is going to function for the rest of a person’s life,” says lead researcher John Gilmore, Thad and Alice Eure Distinguished Professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Certain patterns of connectivity between the amygdala and other regions seem to be associated with anxiety at age 4, the team also found.

The findings have implications for autism research. The amygdalae of young autistic children may have an unusually large number of neurons. And postmortem brain studies suggest the region has structural abnormalities in autistic people.

The findings are in typical children but may serve as a reference for autism researchers, says Denis Sukhodolsky, associate professor of child psychology at the Yale Child Study Center, who was not involved in the study.

Transient ties:

Gilmore and his colleagues recruited 223 children enrolled in the University of North Carolina Early Brain Development Study, which tracks brain development and behavior.

They scanned the children’s brains at 3 weeks, 1 year and 2 years (but did not report results for every child at every time point). They analyzed functional connectivity by measuring the extent to which pairs of brain regions are simultaneously active. The parents completed questionnaires when their children were 4 years old, including an anxiety and self-control assessment.

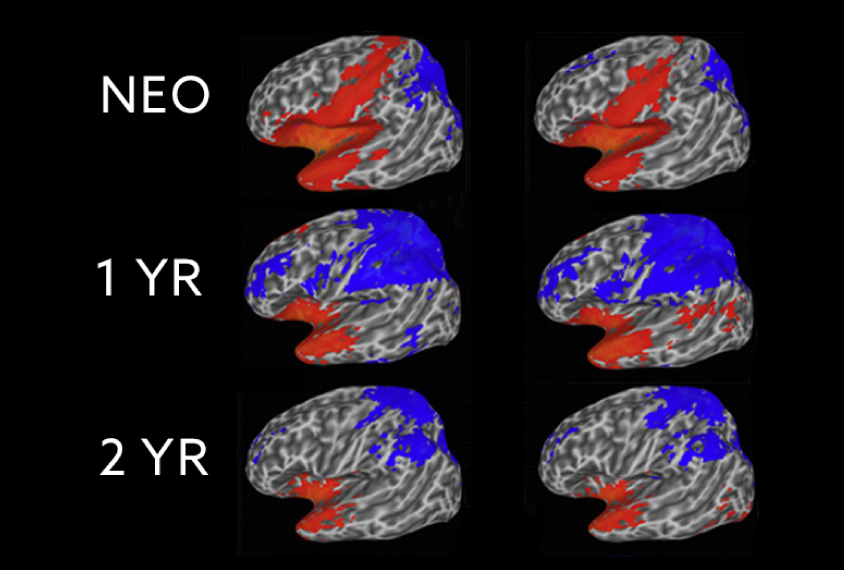

At 3 weeks of age, infants show high connectivity between the amygdala, primary auditory cortex — which processes hearing — and sensorimotor regions, which coordinate sensations with body movements.

These pathways “may help explain the more primitive, emotional responses,” such as crying uncontrollably, in infants, says co-lead researcher Wei Gao, associate professor of biomedical sciences at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

But these patterns change by age 1, when the amygdala works more closely with regions involved in analysis and critical thinking, such as the prefrontal cortex. At this age, children develop more sophisticated ways of expressing emotion, Gao says, such as shaking their heads or exclaiming ‘uh-oh.’ The pattern changes little between ages 1 and 2 years.

“The big take-home for me was, ‘Wow, we really need to start earlier and look at these connectivity patterns in the first six months,” says Christine Wu Nordahl, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the study.

High anxiety:

Early connectivity patterns may also hold clues about later behaviors, such as anxiety, the study suggests.

In some children, connectivity between the amygdala and certain regions doesn’t decrease as early as expected. (This is true of the amygdala’s connections to visual regions as well as to the default mode network, which is involved in self-reflection.) These children are the most likely to be anxious at age 4, the study found.

Unusually low connectivity between the amygdala and regions in the sensorimotor cortex in the second year of life is also associated with anxiety. The work appeared in January in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging.

Understanding how early connectivity patterns involving the amygdala relate to anxiety may shed light on the origins of autism and related conditions.

The researchers intend to scan the participants’ brains and run additional behavioral tests at ages 8 and 10.

“It will be interesting in the future to see how the amygdala continues to develop in their subjects into adolescence, when anxiety and other amygdala-related behaviors become more apparent,” says Cynthia Schumann, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the research.

References:

- Salzwedel A.P. et al. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 4, 62-71 (2019) PubMed

Recommended reading

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Explore more from The Transmitter

Frameshift: Shari Wiseman reflects on her pivot from science to publishing

How basic neuroscience has paved the path to new drugs