Doubts, confusion surround Cognoa’s app for autism diagnosis

The California-based company’s phone application for autism diagnosis is not as far along as initial reports suggested.

The status of a phone application designed to diagnose autism has created confusion among scientists — and sowed skepticism about the app’s efficacy.

According to representatives of California-based Cognoa, the app’s maker, the tool is intended to radically reconfigure the speed and ease with which autism is diagnosed. The company announced in February that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has established that Cognoa’s software is a Class II diagnostic medical device for autism.

It turns out, however, that the agency has not cleared the app, also called Cognoa, for diagnosing autism — nor has it recognized the app as a Class II medical device. “This product is not FDA approved or cleared,” FDA spokesperson Stephanie Caccomo told Spectrum.

The FDA does allow companies such as Cognoa to market an app as a ‘medical device’ to diagnose conditions such as autism, as long as the companies make only limited claims about their app’s accuracy.

For Cognoa’s app, classification as a Class II device would be the first step in FDA approval. (A Class II designation indicates an intermediate level of risk to consumers; for comparison, a pacemaker is a Class III device and a sanitary napkin is Class I.)

Cognoa’s press release was widely covered in the media, however, and many scientists took its phrasing to mean that the FDA had approved the app.

“It kind of surprised me because I hadn’t heard of it before and then it’s popping out with FDA approval,” says Kevin Pelphrey, director of the Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Institute at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. “If I had gotten a question from the audience, ‘Is anything FDA approved?’ I’d go, ‘Yeah, this one thing,’” he says.

Cognoa officials acknowledge that the app is not approved by the agency. Asked about the FDA’s statement, they offered a clarification of the phrasing in their press release.

“Cognoa has been determined to be a medical device intended to diagnose autism. The FDA did not say Cognoa is a Class II device, but we believe that is likely to be the ultimate classification,” says Brent Vaughan, chief executive officer of Cognoa. “We hope to obtain full FDA clearance by the end of 2018.”

In the meantime, many scientists are skeptical about the app’s utility.

The application is “physically beautiful,” says Catherine Lord, director of the Center for Autism and the Developing Brain at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. But, she says, “they haven’t published the data in scientific journals.” Lord developed two gold-standard tests for autism diagnosis: the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).

When she learned of the confusion over the FDA classification, Lord had only this to say: “Oh dear.”

Machine learning:

Cognoa was founded in late 2013 by Dennis Wall, associate professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at Stanford University in California.

Wall explores machine learning’s potential in autism. The company’s stated goal is to develop an app based on machine learning that can help clinicians rapidly diagnose autism.

“The state of the art is dysfunctional because there are too few clinical practitioners to meet the demand,” Wall says. “The practice of detection, diagnosis and intervention needs to be reinvented — and it can be, through mobile technologies.”

The app’s technology builds on Wall’s research. In a 2012 study, for instance, he suggested that a set of 7 questions can diagnose the condition as accurately as the 93-question ADI-R1. (An independent group of researchers was unable to replicate these results in a larger dataset more representative of the autism spectrum2.)

Then, in a 2016 study, Wall’s team tested the screen in 222 children who visited a developmental behavioral clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital. The tool correctly flagged nearly 90 percent of children with autism; it correctly cleared about 80 percent of those without the condition3.

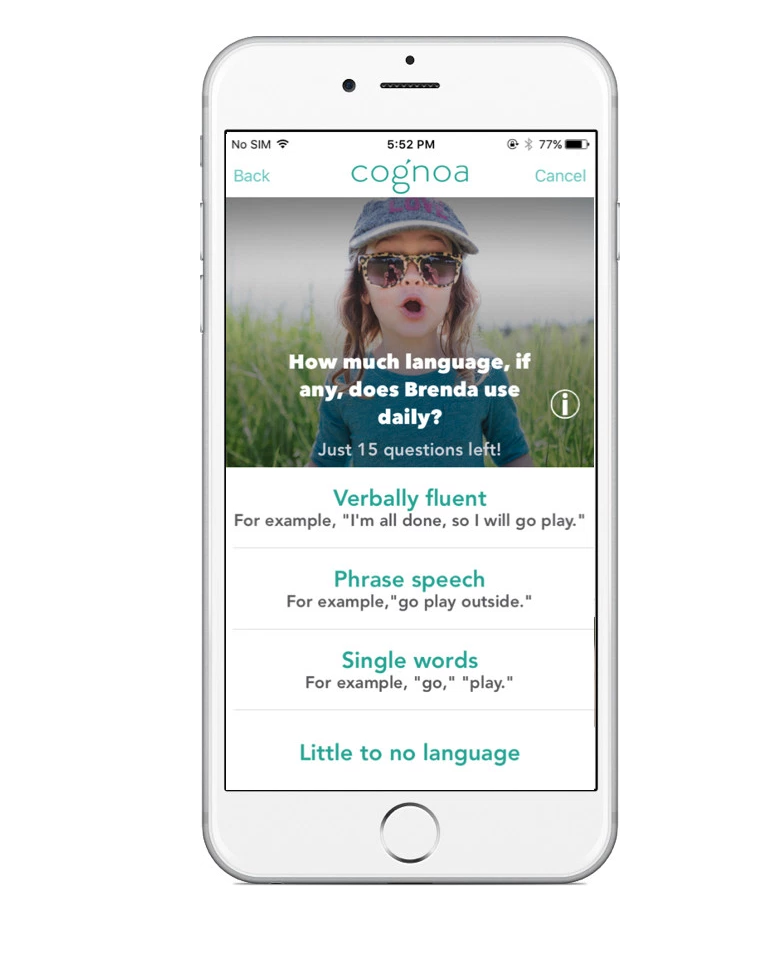

The results helped launch Cognoa, but the company has since developed its own algorithm. (Wall says he is an adviser to the company and does “not have control over their daily operations and direction.”) The app delivers a parent questionnaire with 22 items for children under 4 years and 25 for those aged 4 and older.

It includes questions such as: “Has your child had any developmental challenges so far?” and “Does your child imitate your actions?” Parents can upload videos of their child, which are then scored by at least three Cognoa analysts.

In 2015, the company funded a clinical trial of the app in 230 children, including 164 with autism. The trial measured how well the app stacks up against other autism screens, such as the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers.

The data from the trial was published 7 May in Autism Research. The app performed better than other screening tools at distinguishing children who have autism from those who do not, according to lead investigator Stephen Kanne, executive director of the Thompson Center for Autism & Neurodevelopmental Disorders at the University of Missouri. However, it did so only when the researchers included videos in their analysis. The parent survey alone does not perform better than other screens, Kanne says.

On its website, the company says the app has been clinically validated and is “trusted by 250,000 families.” This number includes everyone who has created an account and used the app, according to Courtney Calderon, a Cognoa spokesperson.

‘Show us the data‘:

So far, the app can only notify parents whether their child is at risk for the condition; it does not provide a diagnosis, although Vaughan and Wall say this is the company’s ultimate aim for the app.

The tool is not meant to replace a clinician’s assessment, says Sharief Taraman, vice president of medical for Cognoa. In fact, he says, “we have a lot of interest from clinicians,” who want to incorporate the app into their practice.

The company plans to release a version of the app for pediatricians, Wall says. This version would be populated with data from parents who complete the app’s questionnaire. Having this information would enable pediatricians to make a diagnosis “far faster than they are making their decisions today,” Wall says.

Other researchers are skeptical, however, and say they want to see more evidence of the tool’s effectiveness.

“Show us the data,” says Tony Charman, chair of clinical child psychology at King’s College London.

“None of [what] we have seen in the published literature has been reliable and valid and sensitive and specific,” says Matthew Goodwin, associate professor of health sciences at Northeastern University in Boston. “Yet [Wall is] going to be taking money out of families’ pockets and out of insurance companies without a research base.” Goodwin was one of the researchers who was unable to replicate Wall’s 2012 study.

Even scientists closely affiliated with the company are circumspect.

“There’s been a paper or two with relatively small sample sizes that clearly don’t represent the diversity and complexity of the conditions that they are hoping that this kind of technology will assist with,” says John Constantino, a member of Cognoa’s scientific advisory board and professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis. “But I think there is promise in what they’re trying to do.”

Kanne says although the trial is supportive of Cognoa’s use as a screening tool, the app is not ready for diagnostic use.

“I’m so opposed to that,” Kanne says. “By calling it a ‘diagnostic measure,’ it might open the door to misuse use in the field.”

Wall says Cognoa has since improved the tool’s diagnostic abilities over the one Kanne used in his study.

The company’s leaders plan to submit the results to the FDA for the app’s approval. They also have “several manuscripts” that they intend to submit to peer-reviewed journals, according to Calderon, and hope to pitch the app to insurance companies, physicians and parents.

References:

Recommended reading

Explore more from The Transmitter