Distinct changes mark brains of people with mutations tied to autism

Deletion of 16p11.2, a chromosomal region linked to autism, leads to the enlargement of certain brain structures, whereas duplication of the same region leads to structures that are unusually small.

Some people missing a copy of 16p11.2, a chromosomal region linked to autism, have unusually large brain structures, according to a new study. Those with an extra copy of the same region show the opposite pattern1.

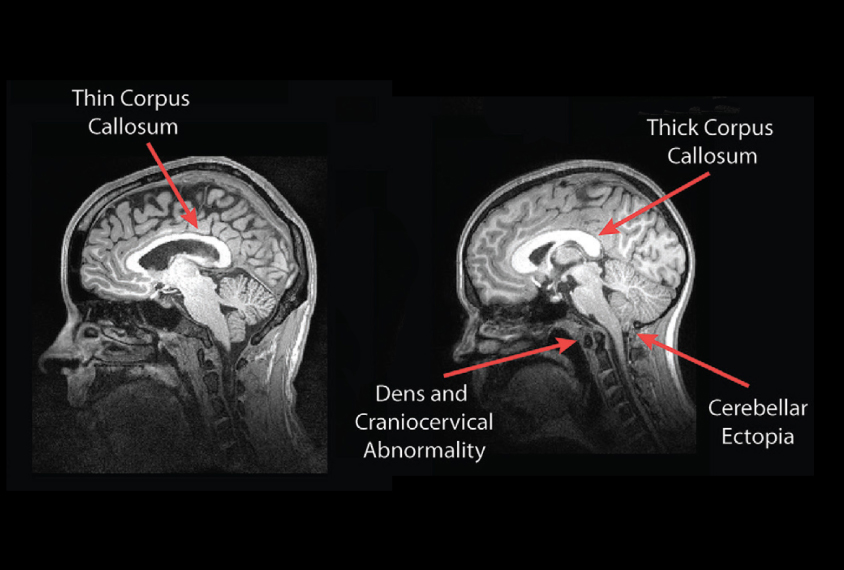

For instance, the band of nerve fibers that connects the brain’s two hemispheres is unusually thick in some people missing a copy of 16p11.2. The same band, called the corpus callosum, is abnormally thin in some people with an extra copy of the region.

People with the deletion and a thickened band have poor social and communication skills, whereas those with a duplication and a thin band score low on tests of intelligence.

The findings suggest that brain scans may one day help identify which children with 16p11.2 mutations are at highest risk for cognitive and behavioral problems.

“I would be very aggressive about getting [these children] into therapy at an early age,” says lead investigator Elliott Sherr, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Deletion or duplication of 16p11.2 occurs in about 0.6 percent of people with autism, making it one of the most common genetic variants tied to the condition.

Sherr and his colleagues examined the brains of 79 people with a 16p11.2 deletion and 79 with a duplication of the region, only some of whom have autism, using structural magnetic resonance imaging. They also scanned 64 of these individuals’ parents and siblings (who do not have either of the mutations), as well as 109 controls.

Expert eyes:

In most brain imaging studies, researchers use computer algorithms to measure brain structure differences between scans. In the new work, two or more radiologists reviewed each scan and simply tallied the presence or absence of abnormalities in the size or shape of 11 different structures.

The researchers took this approach because people can still spot structural abnormalities in scans blurred by head movements, whereas algorithms typically cannot, Sherr says. (People with low intelligence quotients [IQ] are particularly prone to head movements during scanning.)

They found that people with the deletion are more likely to have an unusually thick corpus callosum than their unaffected family members or controls. They also have an enlargement in part of the cerebellum, a brain structure important for coordination of movement, causing it to protrude slightly through the opening at the base of the skull.

By contrast, people with a duplication are more likely to have a thin corpus callosum than are their family members or controls. They also tend to have less white matter, which contains nerve fibers, and have enlarged ventricles, or fluid-filled spaces in the brain. The findings appeared 8 August in Radiology.

The study adds more detailed information to previous findings on brain differences between people with deletion versus duplication, says Bogdan Draganski, associate professor of clinical neurosciences at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, who was not involved in the study.

“It’s building a very nice reference for radiologists to summarize different types of structural abnormalities.”

Shape shift:

The researchers also saw changes in the shape and position of some brain structures, such as an elongation of part of the cerebellum. Algorithms designed to measure structure size might have missed these features.

“This would be hard to see by a computational approach,” says Sébastien Jacquemont, associate professor of genetics at the University of Montreal, who was not involved in the study.

The researchers also measured each participant’s IQ, along with social and language abilities.

People with the deletion who have brain structure abnormalities have poorer social and communication skills than those with the deletion who have typical brain structures. By contrast, people with the duplication who have brain structure abnormalities have lower IQ scores than duplication carriers with typical brain structures.

The findings raise the possibility that structural changes associated with the deletion give rise to autism features, whereas structural changes tied to the duplication predispose an individual to intellectual disability, Sherr says.

The next step is to compare the brain scans of deletion and duplication carriers with and without autism, Sherr says. That comparison might reveal features that define the people with either variant who have autism.

References:

- Owen J.P. et al. Radiology Epub ahead of print (2017) PubMed

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

Proposed NIH budget cut threatens ‘massive destruction of American science’

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals