Dispatches from the 2015 Dup15q Alliance Scientific Meeting

These short reports from our reporter, Nicholette Zeliadt, give you the inside scoop on developments at the 2015 Dup15q Alliance Scientific Meeting.

These short reports from Nicholette Zeliadt give you the inside scoop on developments at the 2015 Dup15q Alliance Scientific Meeting.

Flies catch on for dup15q studies

Fruit flies that carry an extra copy of UBE3A in glia — cells that help to support neurons — have seizures, one of the most common features of dup15q syndrome. Surprisingly, flies that have the same genetic glitch in neurons but not in glia do not have seizures.

Researcher Larry Reiter says he engineered the flies because mouse models of dup15q syndrome don’t have seizures. His team induces seizures by shaking the flies in a laboratory device called a vortex, which is usually used to stir liquids in tubes. “The flies are bouncing around like crazy,” says Reiter, associate professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee in Memphis. “It’s like being in the worst car accident in the world.”

When the chaos subsides, control flies quickly resume their normal activity. But flies with too much UBE3A in their glia lie motionless for a few moments and then twitch violently.

It’s still unclear how or why the extra copy of UBE3A leads to seizures. The mutant flies have fewer glial cells than controls do in the optic lobe, a region of the brain that controls vision. They also have abnormal circadian rhythms and are resistant to the intoxicating effects of ethanol. Eliminating a subset of receptors for gamma-aminobutyric acid, or GABA, a chemical messenger that quiets brain activity, reverses these symptoms.

Reiter and his team are investigating whether interfering with GABA receptors can prevent seizures in the flies. “We can now test different seizure meds [and] do the work that can’t be done in the mouse system at the moment,” Reiter says.

— Nicholette Zeliadt / 31 July

We interrupt your regularly scheduled program…

This morning’s session came to a screeching halt when 63 families of children with dup15q syndrome paraded through a nearby room in the same hotel. The parade marked the start of the 8th International Family Conference, a biennial meeting organized by the Dup15q Alliance.

The room erupted in cheers and applause as the families walked by and an announcer read each child’s name and hometown aloud. “It’s incredibly emotional,” said says Sarah Porath, whose 8-year-old daughter, Annabel, carries an extra copy of chromosomal region 15q11-13. “It feels like we’re coming to a family reunion every time we come to the conference.”

The families flocked to Orlando from as far away as Australia and Switzerland, and as near as Ft. Meyers, Florida. Dup15q syndrome is so rare — it affects an estimated 1 in 12,000 people worldwide — that most first-timers at the conference have never met anyone else with the disorder.

“It’s wonderful to connect with a community of people who have shared experiences and know what you’ve been going through and are going through,” says Guy Calvert, who is chair of the Dup15q Alliance research committee and has a daughter with the syndrome. “It’s also a chance to look at the range of outcomes for those who march through the opening parade, and look into the future to see what the possibilities are for your own kid.”

It was a refreshing reminder that despite the scientific meeting’s focus on molecular mechanisms and clinical features, the ultimate goal is to help individuals with the disorder.

After the parade, I sat on a bench near the parade hall and chatted about the meeting with Paul Karch, chair of the alliance’s board. After a few minutes, his 29-year-old daughter Rachel, who has dup15q syndrome, wedged herself in between us. “I think she’s just decided that I’m talking too much to you, and we’re not paying enough attention to her,” he said.

— Nicholette Zeliadt / 30 July

New autism mouse model debuts at Disney resort

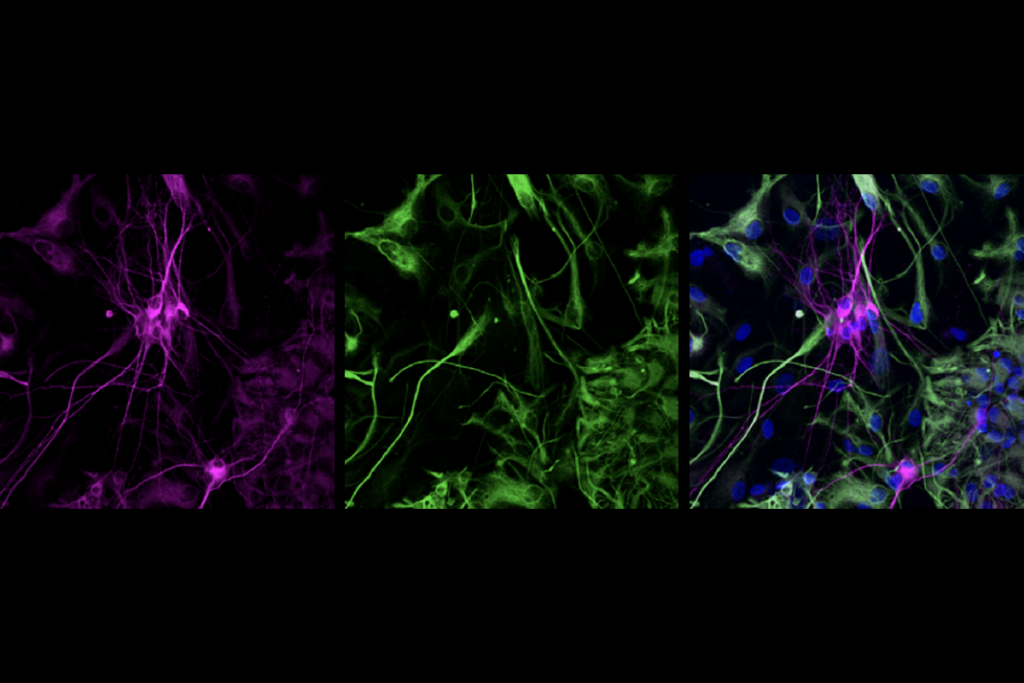

Move over, Mickey: There’s a new mouse in town. Scott Dindot, assistant professor of veterinary medicine at Texas A&M University in College Station, described a new mouse model of autism yesterday at the Dup15q Alliance Scientific Meeting in Orlando, Florida.

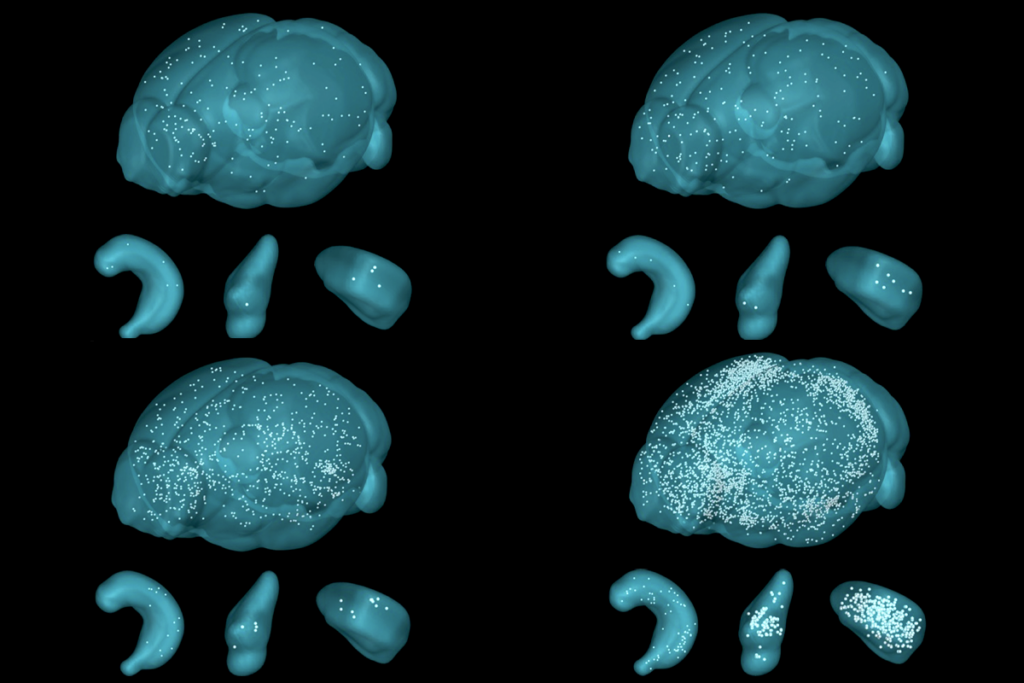

Dindot’s team engineered the animals to produce high levels of UBE3A, an autism-linked gene located in the 15q11-13 chromosomal region. Duplications in 15q11-13 cause dup15q syndrome, which is linked to cognitive impairments, seizures and autism. Up to 3 percent of people with autism carry this duplication, making it the second most common genetic alteration associated with the disorder.

In 2011, researchers led by Matthew Anderson at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston engineered mice with one or two extra copies of UBE3A. Those animals recapitulate the core features of autism, showing difficulties with social interaction and communication, and repetitive behavior.

Dindot and his team decided to develop their own UBE3A mice in 2012 after Anderson’s lab declined to share their animals. (Anderson’s team has since made their mice available for purchase through The Jackson Laboratory, a nonprofit repository for mouse models in Bar Harbor, Maine.)

The new mice overproduce UBE3A specifically in neurons within two brain regions: the cortex, which controls thought and sensation, and the hippocampus, which is involved in learning and memory. The animals also carry a special genetic switch that allows the researchers to turn off UBE3A expression by giving the mice a drug.

Dindot and his team are still working to characterize the behaviors of the mice. In the meantime, they have made them available to other researchers through The Jackson Laboratory. They are also engineering mice that carry alternate forms of UBE3A that are seen in the general population, in hopes of understanding how different versions of the gene affect behavior.

— Nicholette Zeliadt / 30 July

Recommended reading

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Engrams in amygdala lean on astrocytes to solidify memories

Ant olfactory neurons reveal new ‘transcriptional shield’ mechanism of gene regulation