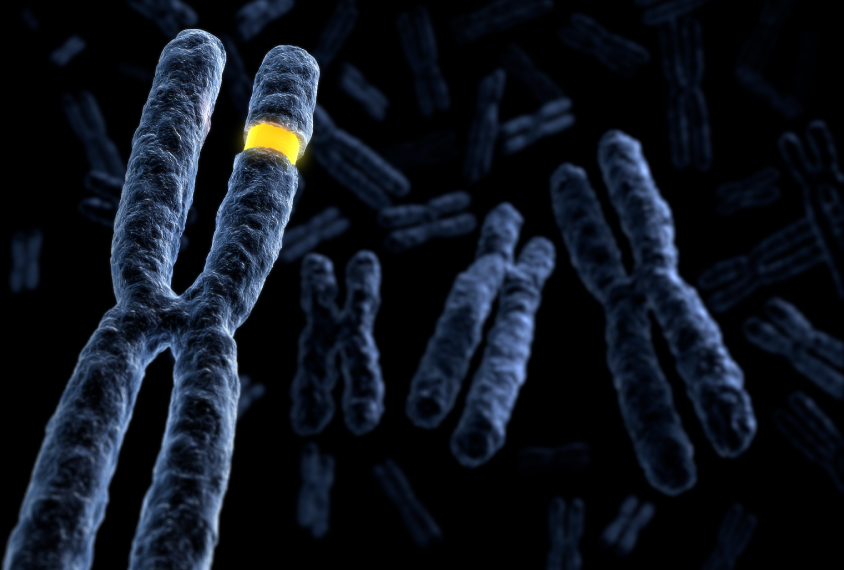

Deletion, duplication of chromosome 16 segment may confer same autism risk

Autism may be just as common among children missing a segment of chromosome 16 as it is in those with an extra copy.

Autism is just as common among children missing a segment of chromosome 16 as it is in those with an extra copy, according to a new study1. The study is the first to carefully characterize psychiatric diagnoses in a large group of individuals who carry these mutations.

The findings are at odds with previous work. A 2011 analysis of more than 3,600 people with autism suggests that deletion of the region, called 16p11.2, is more common among autistic people than the duplication is: occurring in 0.5 percent of them versus 0.282. Other studies have also suggested that deletion of the region has more severe effects than duplication does.

“We were expecting that the deletion carriers might be more severely affected and the duplication carriers potentially less severely affected,” says lead investigator Marianne van den Bree, professor of psychological medicine at Cardiff University in Wales. “But we found no difference in the rates of autism spectrum disorder.”

Duplication carriers are also more likely than deletion carriers to have psychiatric features or diagnoses other than autism, particularly attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the new study found.

Overall, the results echo others linking the region to a variety of psychiatric conditions, says Marwan Shinawi, professor of pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, who was not involved in the work. But the new study is more rigorous because it is based on direct diagnostic evaluations rather than medical records, he says.

“They tried here to have uniform assessments of all the kids,” he says. “The data is really very impressive.”

Same difference:

Van den Bree and her colleagues gave diagnostic tests for autism to 217 children aged 3 to 18 with 16p11.2 deletions and 114 children with duplications. They also assessed the children for five other conditions or traits: ADHD, anxiety, oppositional defiant disorder, intellectual disability and psychotic features. They did the same for 109 of the participants’ siblings, who served as controls.

About 48 percent of deletion carriers and 63 percent of duplication carriers have at least one psychiatric diagnosis, the researchers found. Their analysis shows that people with the duplication have almost three times the odds of any psychiatric diagnosis as those with the deletion.

Autism occurs in roughly one in four people who have either the deletion or the duplication. But only those with deletions are at increased odds of autism compared with controls. Children with either mutation also have increased odds of ADHD and intellectual disability. The work appeared 16 January in Translational Psychiatry.

The findings suggest that mutations in the region have broad effects on brain development, says Christa Lese Martin, director of the Autism and Developmental Medicine Institute at Geisinger Health System in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the study. They highlight the need to better understand the other genetic and environmental factors that lead to the disparate conditions, she says.

Van den Bree and her colleagues plan to track how the diagnoses and traits of some of the participants change over time. They are also comparing psychiatric conditions in people with mutations in other chromosomal regions linked to autism, including 15q11.3 and 22q11.2.

References:

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

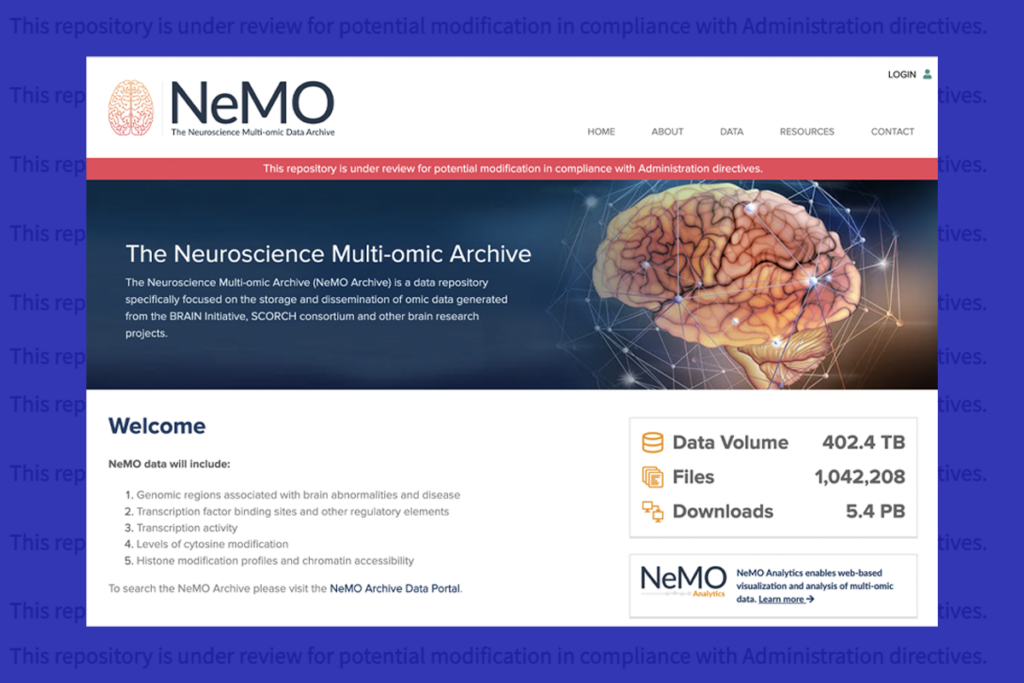

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors