‘Convergence science’ has potential to accelerate research-to-product pipeline

A few years ago, Elizabeth Jaffee, professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, probably wouldn’t have imagined that she would team up with an aerospace engineer to advance her research on cancer therapies.

A few years ago, Elizabeth Jaffee, professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, probably wouldn’t have imagined that she would team up with an aerospace engineer to advance her research on cancer therapies.

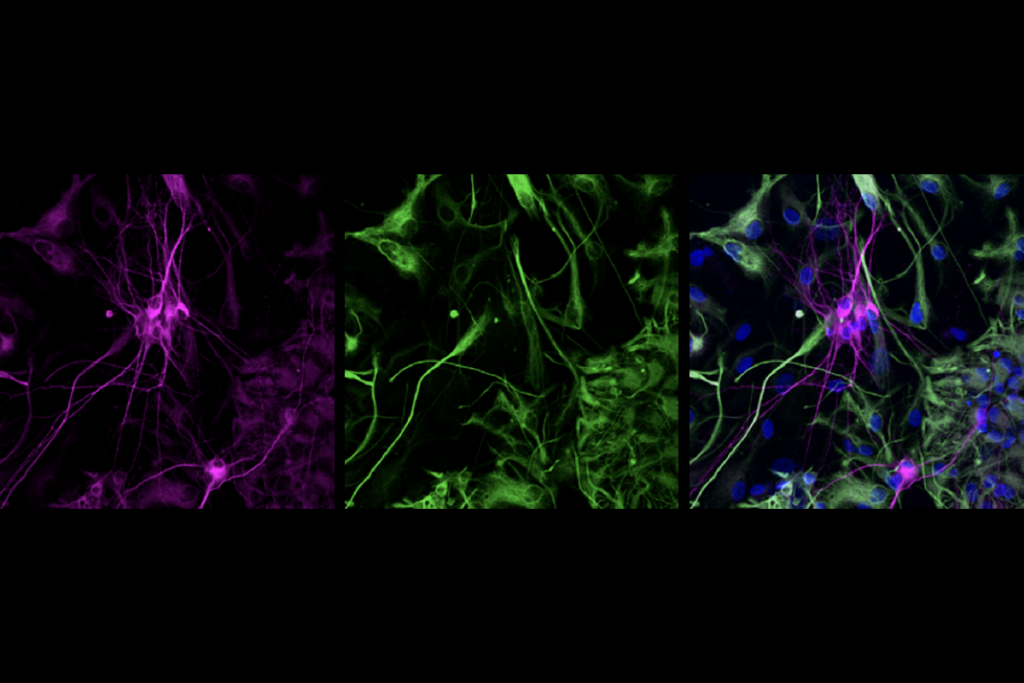

Advancements in mapping out genetic sequences had already given biomedical researchers a wealth of information to study tumors and cells — but they didn’t have existing tools to handle those data. So Jaffee reached out to a professor in the physics department, thinking that the computer system used to analyze complex data from outer space might be able to accommodate the huge trove of information she had on her hands.

“These past 15 years we’ve been going through a technological innovation, and with all the information coming at us, it has all changed how we think about doing science,” Jaffee says.

It’s a trend called ‘convergence’ science, in which scientists increasingly reach across disciplines to collaborate with engineers, technologists and clinicians. In the face of new epidemics and longstanding health problems such as cancer, the research-to-product pipeline needs to be accelerated — a goal that is doable, some scientists say, precisely by encouraging this kind of work.

A group of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers released a report last month to highlight the potential — and challenges — that lie ahead for medical research as it ‘converges’ biology, engineering, mathematics, technology and big data.

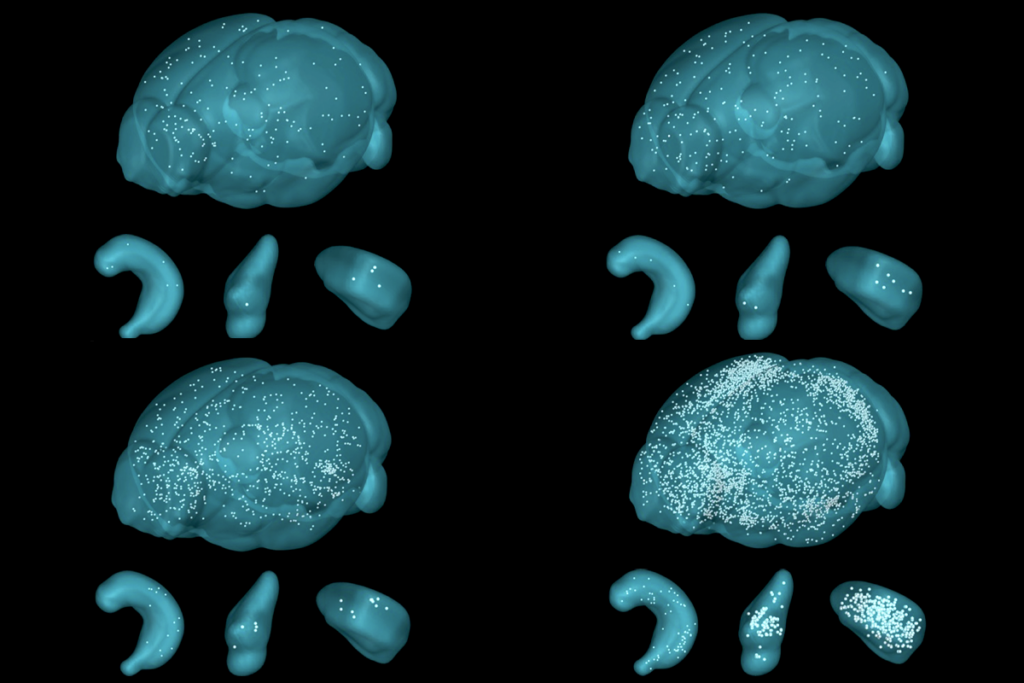

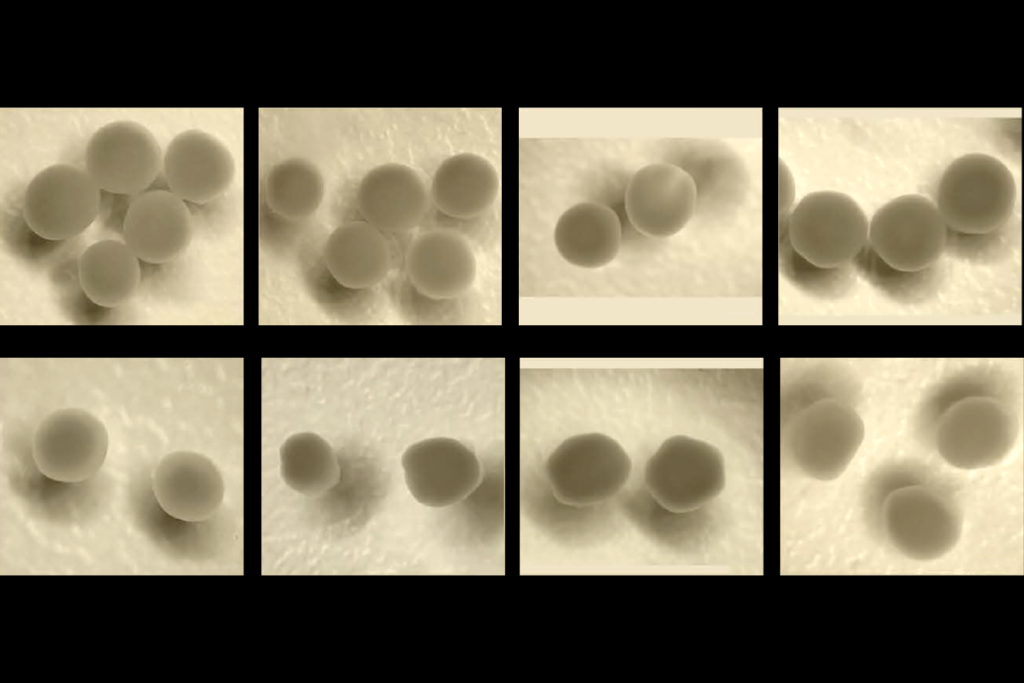

Key areas for advances include the use of nanotechnology for targeted elimination of cancer cells with minimal side effects; three-dimensional printing of living cells to regrow limbs; or the rewiring of genes that can remove disease-carrying vectors — such as mosquitoes — from nature.

“We’re talking about the integration of people who know about the technology with people who know about the science and know about the disease and know about the clinic,” says Tyler Jacks, co-author of the report and the director of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. He points to efforts to develop a Zika vaccine as a research enterprise that has been accelerated as a result of this type of scientific blending.

“I think it offers us much more rapid ways of dealing with those problems,” agrees Phillip Sharp, co-author, MIT professor and Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine.

But these collaborative efforts are not adequately funded, the report suggests, and the researchers who work across disciplines struggle to get acknowledgement from funding agencies, review panels and journal publications.

According to the report, only 3 percent of National Institutes of Health (NIH) 2015 funding was awarded to scientists in engineering, physical science or math and statistics. Budget pressures may be adding to this issue, though a funding increase has been proposed for the NIH this year. Meanwhile, the National Science Foundation, which primarily supports engineering and physical science research, only offers a small amount of support for research that combines these fields with the biomedical sciences.

The report points out, though, that programs such as the president’s Cancer Moonshot Initiative promote collaboration between researchers, doctors, patients and pharmaceutical companies and are encouraging cross-disciplinary research. Funding agencies such as the Department of Energy and the Department of Defense also are beginning to recognize the need. But there is still no single agency that has the primary responsibility to promote convergence.

Scientists don’t have trouble collaborating, says Ethan Bier, professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of California, San Diego.

“I think what would help is to have a funding agency that … tries to forge connections between biologists and physicists by putting significant amount of money into initiatives that would spur investigation in areas that would need those collaborative resources,” says Bier, whose lab recently made the news for applying genetic mutation across a population of insects, a technique that could eradicate malaria-carrying mosquitoes in the wild.

As technology has opened up more opportunities for health research in the past decade, Jaffee believes that these hurdles will be cleared as more scientists seek to work across disciplines.

“I think that is important too that we educate our next generation scientists to easily work between disciplines,” she says.

This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News. It has been slightly modified to reflect Spectrum’s style.

Recommended reading

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky