“In some very real way, memories, thoughts and ideas are somehow locked into separate compartments of the autistic child’s brain.” – Bernard Rimland (1964)

The idea that autism is a disorder of brain connectivity is not new. But it has only become a testable proposition in the past decade, with the development of a range of new neuroimaging techniques and analyses.

Today, ‘underconnectivity’ is considered one of the best-supported theories for the neural basis of autism. But many questions still remain unanswered.

1. What does functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging actually measure?

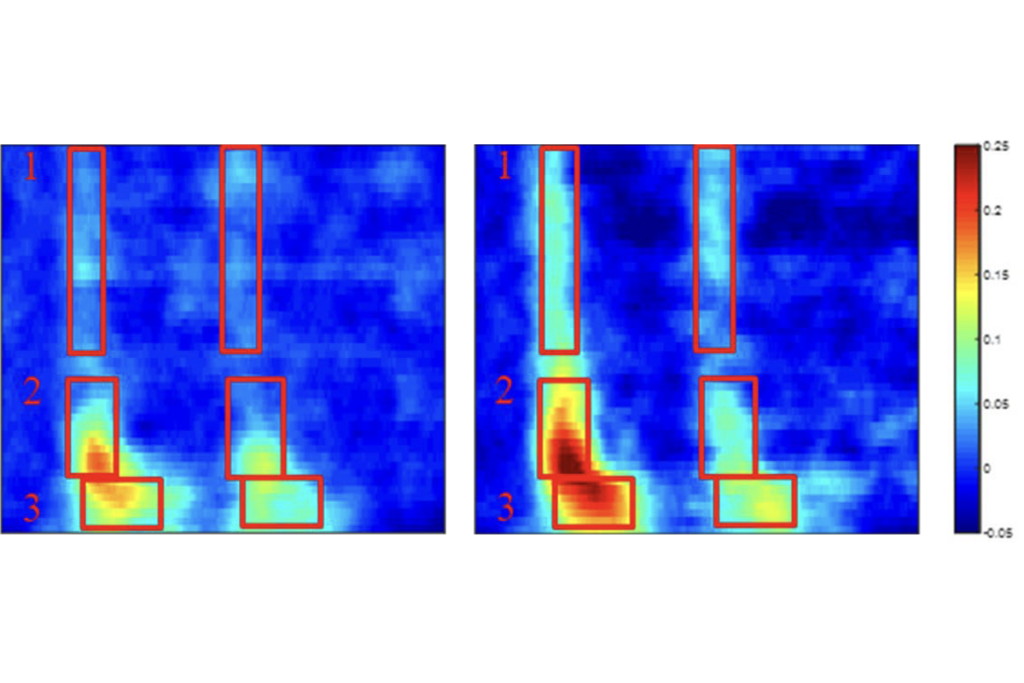

Much of the evidence for underconnectivity in autism comes from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, suggesting that the activity of different brain regions are ‘out of sync’ with one another. fMRI measures neural activity indirectly, via changes in blood oxygen level. These changes are much slower — typically a period of one to two seconds — than the speed at which people are able to think. It’s misleading to speak of the patterns of co-activation that fMRI detects as brain regions ‘talking to each other’1.

So, what does fMRI connectivity actually signify? And how does it relate to differences in cognitive processes that are happening on a much more rapid timescale? fMRI research will continue to be important, but it needs to be complemented by studies using other methods, such as electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography (MEG), that measure brain responses at the speed of thought.

2. How does connectivity relate to genetics?

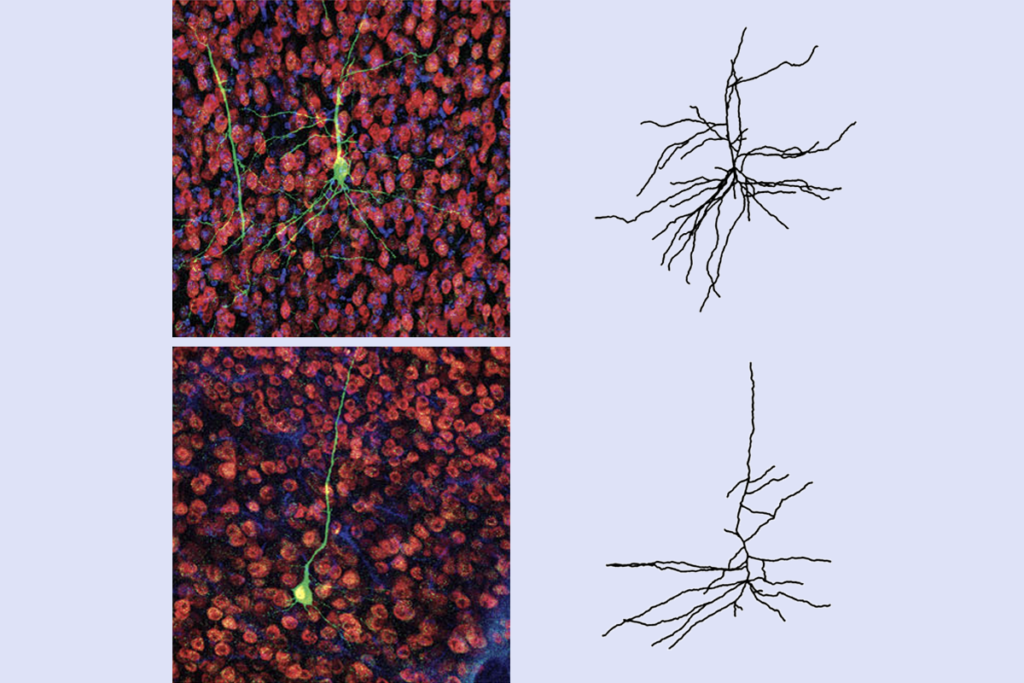

The focus of the connectivity hypothesis is on long-distance connections, particularly between the front and the back of the brain. However, most of the genetic variations that have been linked to autism appear to act at the synapses — the gaps between individual neurons. An important challenge for the connectivity theory is to explain how these differences at the microscopic level ultimately translate to much larger-scale changes in long-distance connectivity.

3. Is disconnection a cause or a consequence of autism?

Most of the evidence for connectivity differences in people with autism comes from adults. That leaves open the possibility that abnormal connectivity patterns are a consequence rather than a cause of autism2. In the past few years, there have been a number of studies indicating that atypical connectivity can be found in young children with autism. Still, as evidence grows that signs of autism are apparent in the first year of life, teasing apart cause and effect is going to be extremely difficult.

4. How is brain connectivity affected in relatives of people with autism?

Surprisingly, there is little research on brain connectivity in relatives of people with autism. If brain connectivity is atypical in apparently unaffected siblings, this would be evidence against the idea that underconnectivity is a consequence rather than a cause of autism. But it would also indicate that underconnectivity on its own does not necessarily lead to autism.

5. If there are ‘many autisms,’ are they all disorders of connectivity?

As in most other areas of autism research, studies of connectivity tend to report only whether there are significant differences between overall groups, rather than patterns among individuals. Given how variable the outward signs of autism can be in different people, we should expect similar variability in their brains. This may help explain why different imaging studies often come up with inconsistent results.

What’s more, imaging studies are heavily biased toward high-functioning individuals, who are better able to cope with the demands of scanning. In fact, many studies deliberately exclude participants whose intelligence quotients are outside the normal range. As a result, we know very little about connectivity in people with more severe forms of autism.

6. How does autism differ from other connectivity disorders?

Underconnectivity is considered to be a theory of autism. But there is also evidence for atypical brain connections in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, dyslexia, schizophrenia, dementia and language impairment, to name just a few.

So how is the connectivity disorder in autism different than in these other conditions3? Is it the specific connections that are affected? Or are there differences in the underlying causes of disconnection?

Jon Brock is a research fellow at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. He also blogs regularly on his website, Cracking the Enigma. Read more Connections columns at SFARI.org/connections » Read more from the special report on connectivity »

References:

1: Thai N.J. et al. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 73, 27-32 (2009) PubMed

2: Pelphrey K.A. et al. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 52, 631-644 (2011) PubMed

3: Wass S. Brain Cogn. 75, 18-28 (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Explore more from The Transmitter

New findings on Phelan-McDermid syndrome; and more