Confusion at the crossroads of autism and hearing loss

Hearing difficulties and autism often overlap, exacerbating autism traits and complicating diagnoses.

A

t the age of 3, Tyler spoke only about five words at a time, often with a stutter. Doctors initially thought he was deaf, and experts diagnosed him with auditory dyssynchrony, a condition that alters how the brain processes sound. But subsequent evaluations revealed that Tyler’s hearing was just fine.Yet as Tyler grew, his speech problems — along with other atypical traits — led to a host of diagnoses, including speech apraxia, dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. His father, Tim, always felt there might be a more cohesive explanation for his son’s melange of issues. (To protect the boy’s privacy, Spectrum is withholding the family’s last name.) Tyler lagged on certain motor skills, such as the ability to walk in a straight line, and had unusual sensory traits, such as a constant need to touch and smell things. “We went down so many rabbit holes trying to figure out if all this stuff was somehow connected,” Tim says.

Late last year, when Tyler was 11, his parents signed him up for a study on speech impairments. The researchers, at the University of California, San Francisco, verified that Tyler’s ears work but found that his brain has trouble discriminating words from background noise. He also struggles to identify rapidly presented sounds, which may be the cause of his slow, halting speech. Taken together with the boy’s sensory traits and delayed motor skills, the researchers wondered if he was on the spectrum. An autism evaluation confirmed their hunch.

It was a revelation to the family. Tyler is sociable and has never had issues with making eye contact, a classic characteristic of autism. “He’d been diagnosed with a hodgepodge of different things,” Tim says. “But [until then], nobody suggested he could have autism.”

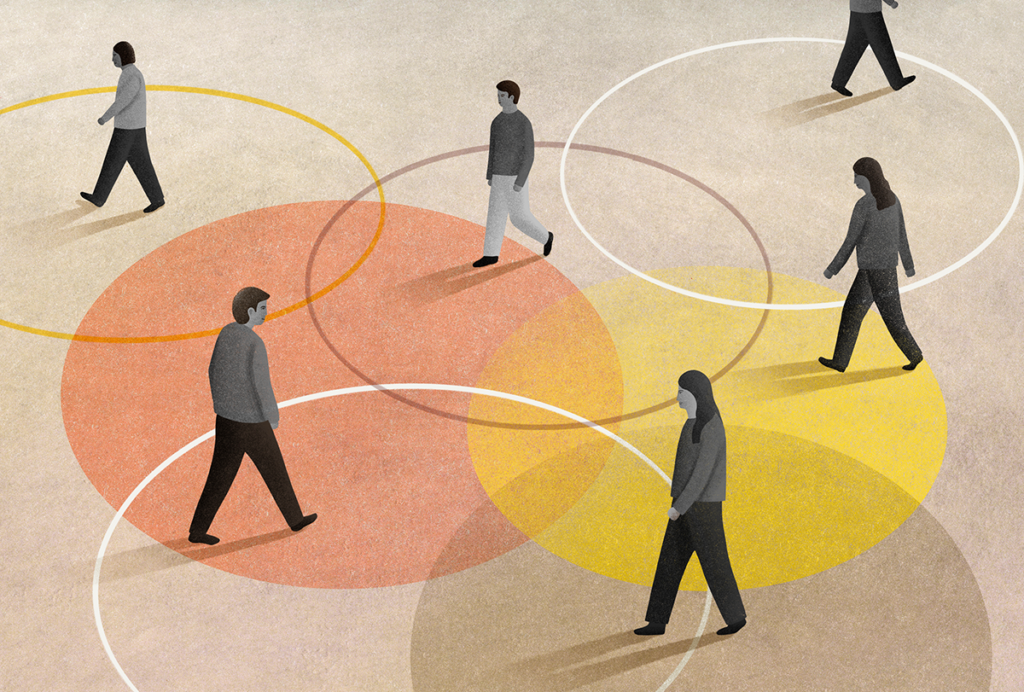

A late autism diagnosis such as Tyler’s is just part of the confusion that can arise when hearing problems and autism overlap. Most people know that children with autism can be unusually sensitive to certain noises, such as the roar of a vacuum cleaner or the commotion of a busy shopping mall. Less well recognized is that many people on the spectrum experience hearing difficulties, including conditions that disrupt the brain’s processing of sounds. Just how frequently these difficulties coexist with autism is still unknown. But studies hint that hearing problems are at least three times as common in autistic people as in typical people. Among deaf or hard-of-hearing children, autism occurs in an estimated 4 to 9 percent, compared with only 1 percent of children in the general population, some reports suggest.

Similar biology may underlie some hearing problems and autism, says psychologist Jean Mankowski of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For instance, premature birth and infections with rubella or cytomegalovirus in the womb are associated with a higher likelihood of both hearing problems and autism. Prematurity, infections or other conditions can alter how neurons form connections in the fetal brain, which in turn may interfere with hearing or contribute to behavioral traits.

Whatever the reasons for the overlap between hearing problems and autism, doctors often conflate the two, causing them to miss one diagnosis or make an incorrect one. They may attribute a young child’s difficulty understanding and producing speech to hearing impairments rather than autism’s hallmark social and communication difficulties. “I’d frequently hear from colleagues, ‘There’s this deaf child who seems to have characteristics of autism, but nobody’s evaluating that,’” says Jackson Roush, an audiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Or the other way around: ‘This child seems autistic, but we think it may be more related to hearing loss.’”

If someone has both conditions, it may take years before both are correctly identified. And a failure to make the right diagnostic calls can mean lost opportunities to address a child’s actual needs at the right time. Children who are deaf or hard of hearing already have an increased likelihood of being deprived of language during critical periods of brain development. Throw autism into the mix and those odds likely run even higher, says Aaron Shield, a language acquisition expert at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

To prevent children with both conditions from slipping through cracks, investigators are mapping out the overlap to gain insights into how even subtle auditory problems without hearing loss may hinder communication skills. And they are beginning to optimize diagnostic instruments and interventions for deaf and hard of hearing children with autism. “Earlier diagnosis of autism could help parents and teachers be aware of additional support a deaf child with autism might need in order to acquire language,” Shield says.

Auditory effects:

T

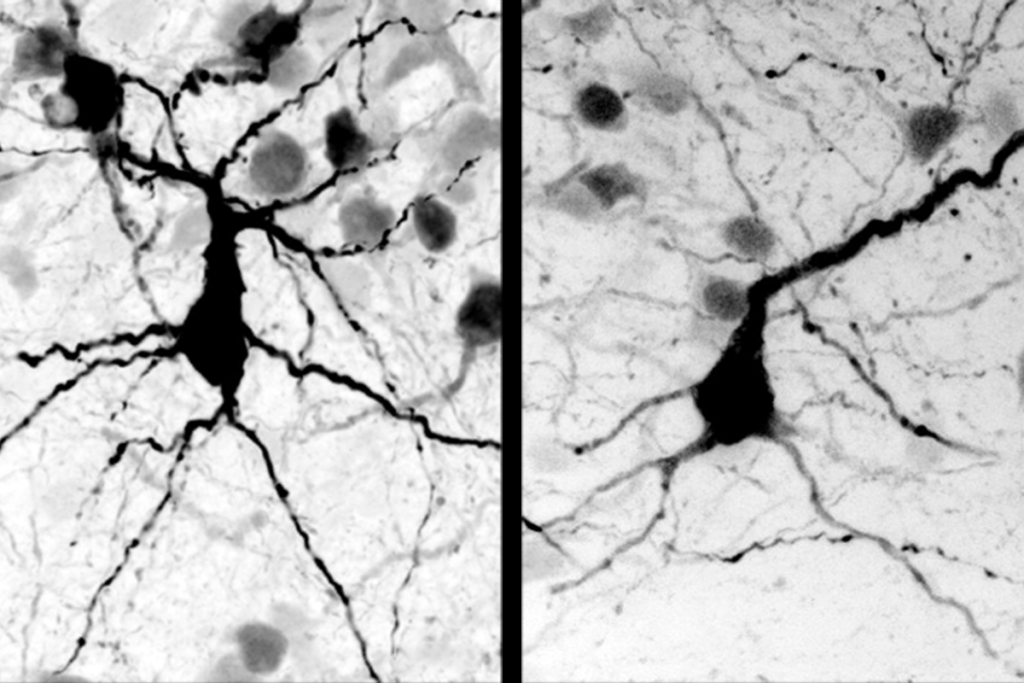

ypically, sound waves cause the eardrum, located in the middle ear, to vibrate — a thrum that is picked up by nearby membranes and bones. The vibrations travel to the inner ear, triggering ripples in the fluid-filled, spiral-shaped organ called the cochlea. There, cells covered in tiny hairs sense those perturbations and convert them into nerve impulses. The electrical signals zip to the auditory processing region of the brain, to be parsed into birdsong, laughter and other sounds.Hearing snafus can ensue if parts of this relay system break down. The peripheral hearing system — the eardrum, bones or cochlear fluid — might not respond properly to a sound. Or the brain’s auditory region might fail to make sense of incoming information. More subtle issues, such as difficulty distinguishing sounds, can result when the neural circuits that process sound err.

One of the earliest reports of hearing impairments in people with autism is a 1977 survey from the Medical Research Council in London, England. Experts tested middle-ear function and the ability to hear pure tones in 16 children with autism aged 8 to 15. A few children had partial hearing loss, and most showed abnormal responses within the ear.

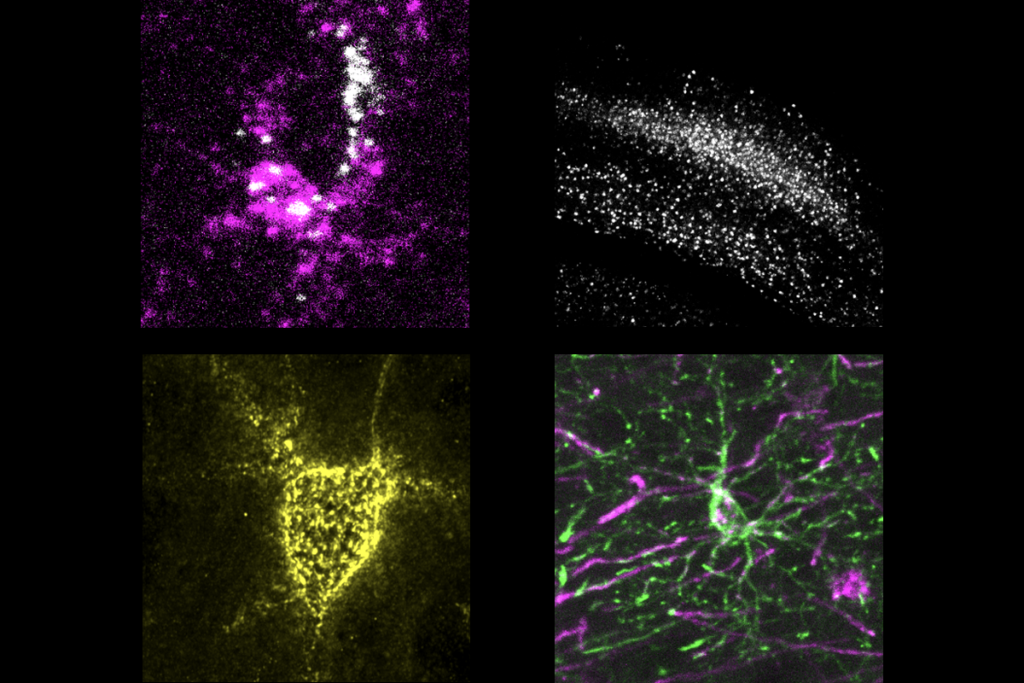

Over the following decades, technological advances paved the way for new discoveries linking autism and hearing conditions. Today researchers can decode the ability to hear sounds at specific frequencies and gauge how well middle-ear membranes respond to air pressure changes. They can use electroencephalography (EEG) to monitor how sounds are processed in the brain and to detect auditory deficits in someone whose ears otherwise function well.

Thanks to these tools, researchers can probe in depth how hearing problems can influence autism traits — in particular, delayed speech and language development and problems recognizing others’ emotions. Many children with autism have halting, monotonous or inarticulate speech. One-third are minimally verbal, and untold numbers have co-occurring auditory processing difficulties.

A groundbreaking 2016 study found that about half of autistic children have at least one kind of peripheral hearing problem, compared with only 15 percent of their typical peers. And these problems manifest in subtle, nonobvious ways, such as unusual sensitivity to sounds in one ear or involuntary muscle contractions in the middle ear that distort sounds. For some, there are signs that the cochlea amplifies and transmits sound differently.

The study turned up something else intriguing: Autistic children who experience hearing difficulties at frequencies around 2,000 hertz — the middle range for human speech — themselves have distorted speech. “I wasn’t expecting to find a strong relationship with communication abilities,” says lead investigator Carly Demopoulos, a neuropsychologist at the University of California, San Francisco. For these children, incoming speech sounds may be altered in some way, thwarting their ability to understand and replicate those sounds, she explains. Any distortions in — or inability to hear — the sound of one’s own voice might also make it tougher to learn to speak clearly.

Auditory processing difficulties in autism might manifest as hypersensitivity to noises or an inability to tell sounds apart, according to other lines of research. For instance, in large gatherings, people without processing issues can usually follow a single conversation while ignoring laughter or, say, the clink of silverware in the background. “Their brains are able to focus attention on this relevant stream of sound they’re trying to interpret,” says neuropsychologist Helen Tager-Flusberg of Boston University. But “some autistic kids have great difficulty with this.”

That difficulty may contribute to speech problems. In 2015, Tager-Flusberg and her colleagues used electrodes to track the brain activity of autistic and typical adolescents as they heard unexpectedly loud or soft sounds amid a background din that mimicked a party. The brain activity of the teenagers varied greatly, the researchers found, but only in minimally verbal youth did neural responses correlate with reactions to sounds in everyday life, as measured by a questionnaire the teenagers’ parents completed.

A follow-up study to be published this month in Autism Research provides additional support for a connection between sound processing and verbal ability: It finds that minimally verbal autistic adolescents and young adults have trouble distinguishing their own name from someone else’s and have a markedly different neural response to the sound of their name than verbal young people with autism and typical people do. “It’s not that their brain doesn’t pick up the sound itself, but it fails to attribute importance to the sound,” Tager-Flusberg says. Such findings may help explain why some individuals on the spectrum often feel overwhelmed in noisy settings.

Hearing difficulties can also obscure emotions conveyed by another person’s tone of voice. In 2015, Demopoulos’ team asked autistic and typical children to identify the emotional tone of someone saying, “I’m going out of the room now, but I’ll be back later” in a happy, angry, fearful or sad voice. The researchers also took magnetoencephalography recordings as the children listened to a series of tones. The autistic children who took a long time to process the tones or had trouble processing a rapid sequence of tones also tended to struggle with interpreting the speaker’s tone. “It didn’t matter what any of the words were in that sentence,” Demopoulos says.

Tangled traits:

O

n the flip side, autism can complicate the communication challenges of deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Charlie Hughes, 25, of Nottingham, England, was diagnosed as autistic at age 2 and had progressive hearing loss, possibly as a result of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, such that he became profoundly deaf. His parents chose not to fit him with hearing aids because “they didn’t want me to get picked on for ‘looking deaf,’” he recalls, chatting via text on Skype.Hughes could not speak until he was 8 years old, but he started learning British Sign Language and lip-reading in preschool. He flourished under formal sign-language training along with exposure to social cues, albeit incidental ones: Engaging with the deaf community over the years improved his reading of body language, he says, and helped him overcome some of the social obstacles of being autistic. Three years ago, he graduated from university with a degree in forensic science.

Sometimes, a child who is deaf or hard of hearing can keep pace with her hearing peers if her hearing issues are diagnosed and addressed via cochlear implants or signed languages early on. But adding autism can create new hurdles. “It makes it even harder to expose them to enough language to develop and grow,” Shield says. Children with autism are often uncomfortable with eye contact and may have trouble with joint attention, in which two people focus on the same object together. They also may find it challenging to process facial cues. “Being able to do these things is really important for learning sign language,” Shield says. “So, the earlier autism is diagnosed in deaf and hard-of-hearing children, the greater the chance for effective interventions.”

Even so, children with autism whose parents have taught them a signed language from birth often reverse signs that have a specific palm orientation (inward or outward) or refer to themselves by signing their name instead of using pronouns, akin to similar idiosyncrasies seen in hearing autistic children, Shield has found. And deaf autistic children who use a signed language also tend to repetitively echo what an adult signs to them, just as hearing autistic children may arbitrarily repeat words they hear — a tendency called echolalia.

Deaf children with autism who do not learn to sign from an early age like Hughes did need tailored interventions to catch up, says child and adolescent psychiatrist Barry Wright of the University of York in England. For instance, a deaf typical child may need supports such as visual calendars or cues for routine activities to compensate for lost language exposure. An autistic deaf child may need similar language support, coupled with social and behavioral interventions to address problems with eye contact or with interpreting facial expressions.

For many children with autism and hearing issues, the autism goes undiagnosed for years, experts say. Parents and clinicians tend to focus on the most obvious issue, such as the stuttering speech patterns Tyler has. “Sometimes families have put so much work into making sure the speech and language needs are met, that they can possibly miss some red flags,” Mankowski says. “Families are a bit blown away when we say, ‘We’re seeing these traits; do you mind if we rule out autism here?’”

That elimination process is complicated by a lack of reliable clinical tests. Instruments such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule are not designed for the deaf or hard of hearing. These assessments often include questions about whether a child responds to the sound of her own name or speaks in a monotone or an otherwise unusual pattern. As a result, among deaf or hard-of-hearing children, the tests may flag autism in children who are not autistic. Alternatively, if a clinician chalks up some of the answers to hearing problems, an autistic child may not make the diagnostic cutoff.

Deaf children can be mistaken as autistic for other reasons, too. Unable to hear, they may fixate on other sensory cues. Wright recalls speaking with teachers and parents who were concerned about autism in one deaf child simply because this child spent long stretches alone in a corner of the school playground, tossing leaves into the air and watching them flutter down.

Given these challenges, it can take years to understand the full scope of a child’s autism and hearing issues. For example, only last year did Hughes learn that there are multiple layers to his auditory challenges. Because he wanted to work on his speech and not have to rely so heavily on interpreters, he sought out an audiologist to get hearing aids.

“The [hearing aids] have been fairly useful for things like alarms and not getting run over by cars,” he says, “but not as much for speech, because it’s hard to filter it all.” The devices amplified other people’s voices — but he did not necessarily understand them, he says. Further testing revealed for the first time that Hughes also has an auditory processing disorder, such that his brain does not process sounds correctly. He plans to get additional tests to determine whether specialized hearing aids might help.

Clinicians are developing tools to decrease diagnostic delays and improve outcomes for autistic children with hearing issues. Wright and his colleagues have adapted the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule for the deaf and hard of hearing by creating signed-language equivalents for questions that make reference to spoken words or phrases. They have tested and validated the adapted version in deaf and hard-of-hearing children across 10 centers in the United Kingdom. Other investigators are evaluating tools such as Language Environment Analysis (LENA), which records and analyzes children’s word production in natural settings, to distinguish speech patterns in autism from those in altered hearing.

Another approach is to focus on early detection of inner-ear problems that contribute to speech processing difficulties in children, including those with autism. Researchers have used an earplug-like device, outfitted with tiny microphones and speakers, to pick up inner-ear responses to a series of clicks and beeps; the test could potentially be administered at birth, much like the newborn hearing screen in the United States, researchers say.

And Roush, Mankowski and their colleagues have established a clinic at the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities in Carrboro, North Carolina, to help identify autism and related conditions in deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Diagnoses at the clinic are a team effort and include opinions from an audiologist, psychologist, speech-language pathologist and occupational therapist. “There are many things we consider about behavioral differences that would be above and beyond what’s seen in children with hearing loss alone,” Mankowski says.

Such clinical expertise could spare families like Tyler’s years of bouncing around from one specialist to another in search of answers. Learning that Tyler has autism has helped Tim and his wife come to terms with the boy’s needs. Their son’s first school focused on mainstreaming typical deaf children, a poor fit for a child who is neither hard of hearing nor typical. This year, Tyler plans to attend a private middle school for typical children with dyslexia, which Tyler also has. Looking back, Tim says, the family made decisions about Tyler on the assumption that he was a typical child with delayed speech and learning disabilities. If the family had known Tyler was autistic from the beginning, Tim says, “it might have made an enormous difference.”

Recommended reading

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: How goats can model neurodegeneration