Conflicting messages

Two contradictory studies prompt questions about the reliability of self-report questionnaires in autism.

How accurately can children with autism report their levels of anxiety or depression? Two studies have published opposing findings on the reliability of self-reporting in autism, leaving researchers with no clear answer.

The literature in autism is replete with small, contradictory studies. That means that researchers can pick and choose evidence that best fits their ideas about autism.

For example, a new study, published 8 September in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, endorses self-reports as a legitimate way to assess anxiety and depression in children with autism.

But a 2011 study of about the same size, published in Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, upholds the opposite message.

Anxiety disorders are common among individuals with autism, affecting up to 80 percent of people with the disorder.

In the new study, 30 high-functioning children with autism and 21 controls filled out surveys about their levels of depression and anxiety. Their parents also answered questionnaires about their children’s well-being.

For the most part, the answers from children with autism agreed with those of their parents, suggesting that the children can accurately assess their own problems. (Interestingly, in the control group, the answers only agreed when assessing depression.)

The results also indicate that the children with autism may be good candidates for cognitive behavioral therapy, a technique that helps individuals change their emotional response to situations, the researchers say.

This is all great news for researchers, and for people with autism and their families. However, nothing in autism research is that simple.

The 2011 study came to exactly the opposite conclusion, saying that self-report measures are not an accurate way of assessing the mental health of children with autism. That study investigated four self-report questionnaires for depression, anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Like the new study, the 2011 study has small numbers, with 38 high-functioning children with autism, mainly boys, but no controls. It found that the self-report tests for depression and ADHD each missed a large number of children who have the disorders. The test for OCD over-reported the condition, and the survey for anxiety disorders underreported it.

Based on these findings, the researchers urged their colleagues not to rely too heavily on self-report questionnaires for clinical diagnoses of children with autism.

Given the difficulty in accurately diagnosing autism, and given the disorder’s notorious heterogeneity, it seems this more cautious view is probably a safer bet.

Recommended reading

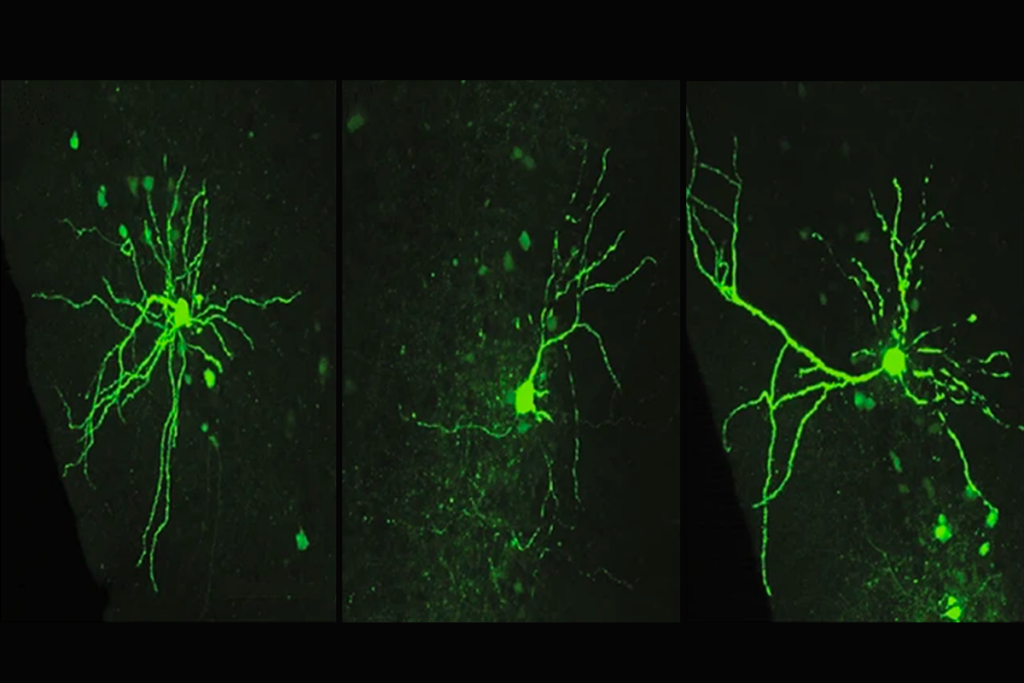

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

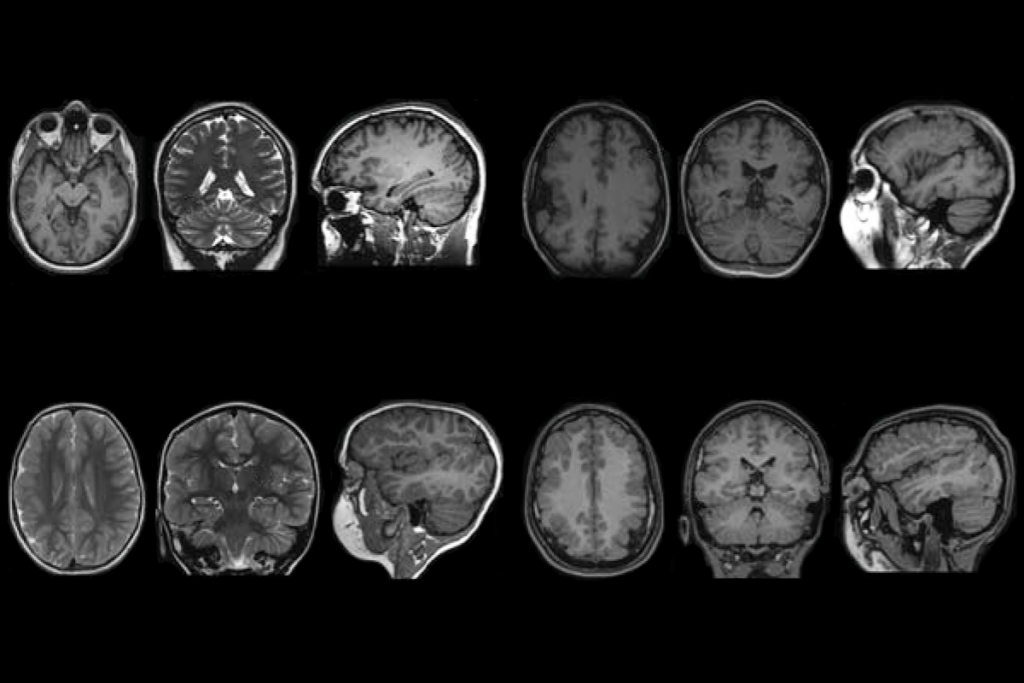

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence