Hello, and welcome to this week’s Community Newsletter! I’m your host, Chelsey B. Coombs, Spectrum’s engagement editor.

This week, we’re starting with a thread by Yu-Lun Chen on Autism’s Twitter account. Chen is a graduate student and adjunct faculty member in occupational therapy at New York University in New York City.

New #OpenAccess paper by @YuLunChen_OT & @Kpk3P examining the role of neurotype match in peer interactions in inclusive educationhttps://t.co/KWI36wcKVV

A thread ????:

— Autism Journal (@journalautism) June 29, 2021

Chen unpacked a paper, based on her dissertation, that looked at peer interactions among autistic and non-autistic students over five months. Previous research suggests two people with different life experiences can have difficulty relating to each other, described as the ‘double empathy problem.’ In the new work, autistic and non-autistic people were indeed more likely to interact with those who matched their neurotype — a preference that strengthened over time. And those same-group interactions were more about “sharing thoughts and experiences rather than requesting help or objects.”

“These findings suggest that peer interaction is determined by more than just a student’s autism diagnosis, but by a combination of student and peer neurotypes,” the authors wrote.

Autistic students interacted with their autistic peers in similar patterns as non-autistic students did with their fellow non-autistic students. Thus, autism may not be a personal social impairment, but rather a communication challenge between individuals.

— Autism Journal (@journalautism) June 29, 2021

Noah Sasson, associate professor of behavioral and brain sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas, called the paper “really impressive.”

This is a really impressive paper! It studies natural peer interactions among autistic and non-autistic adolescents over a 5 month period. Within-neurotype interactions grew over time and were more relational and included more sharing of experiences than cross-neurotype ones. https://t.co/uns12mbEUk

— Noah Sasson (@Noahsasson) June 25, 2021

The next tweet comes from Laura Crane, associate professor of psychology and human development at University College London and deputy director of the Centre for Research in Autism and Education in the United Kingdom. She and her colleagues reviewed autistic people’s self-reports on camouflaging, or masking to hide their autism traits.

New @journalautism article led by @DrJuliaCook (with @WillClinPsy @lauralhull @lauraeabourne and me): Self-reported camouflaging behaviours used by autistic adults during everyday social interactions https://t.co/4mhy5IEQPJ #openaccess

— Laura Crane (@LauraMayCrane) June 28, 2021

The study identified 38 different camouflaging behaviors and earned high praise on social media. Lily Levy, a child and adolescent mental health services clinician in the U.K., said she was “certain this is going to be my paper of the year for 2021.”

This may be a bold shout with half the year remaining, but I’m certain this is going to be my paper of the year for 2021. pic.twitter.com/dh4HhIQSnT

— Lily Levy #BLM (@lilyhannahlevy) June 28, 2021

Ann Memmott, an associate and ‘expert by experience’ at the National Development Team for Inclusion in the U.K., wrote that it was a “[very] useful list of some of the ways we hide that we’re autistic, and commentary on why we have to, or choose to, do this. “

https://t.co/LbaPquE5Gp Lovely new research about autistic people who camouflage/mask, and why. V useful list of some of the ways we hide that we’re autistic, and commentary on why we have to, or choose to, do this. Exhausting, frankly.

— Ann Memmott PGC???? (@AnnMemmott) June 30, 2021

Our final paper comes from Audrey Brumback, assistant professor of neurology and pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin, and Meredith McCarty, a graduate student at the university.

Beyond excited to share my first first-author paper, in collaboration with @BrumbackLab ! https://t.co/hlsv7o9Eut

— Meredith McCarty (@Neuro_Meredith) June 14, 2021

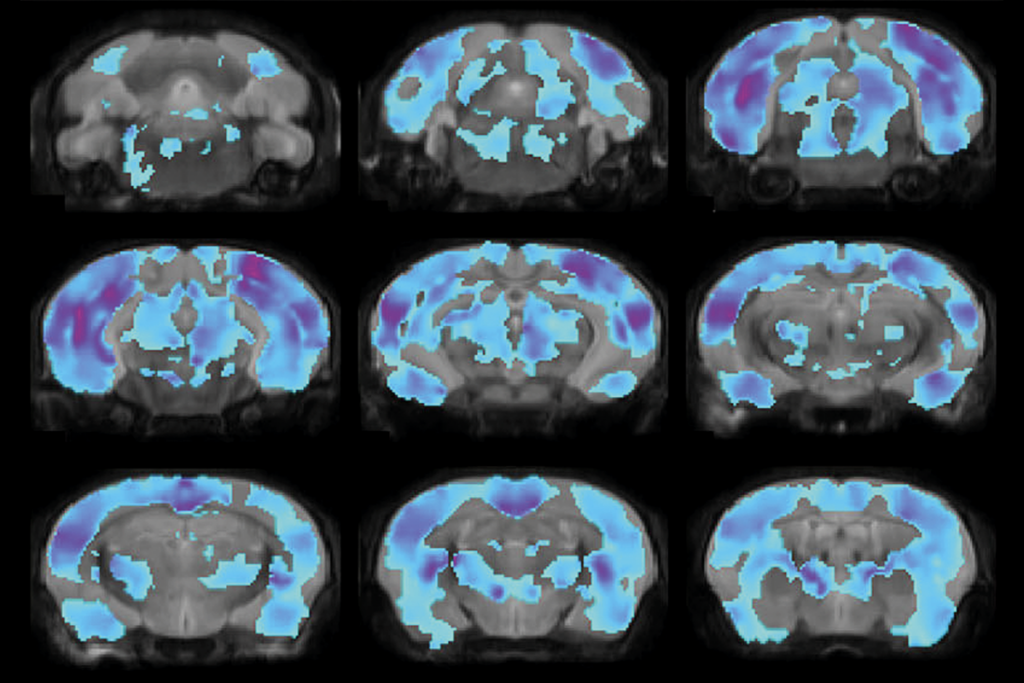

The pair investigated stereotypies, or stereotyped repetitive movements in autism, also known as stimming. Stimming may change brain rhythms to enhance both sensory processing and attention, they say, and they propose ways to experimentally examine this — something that hasn’t been done, despite autistic people having said that stimming improves their sensory processing.

“We hope that by understanding the anatomy and physiology of motor stereotypies, we can make them less stigmatizing and develop ways to harness their benefits to help people with and without autism,” the authors wrote.

Thanks, @Neuro_Meredith! It was a real honor to work on this with you. I hope it helps destigmatize #stimming in #autism and helps us think in new & different ways about how our brains are wired up. https://t.co/ZpyDTviXJb

— Audrey C. Brumback, MD, PhD (@BrumbackLab) June 15, 2021

That’s it for this week’s Community Newsletter from Spectrum! If you have any suggestions for interesting social posts you saw in the autism research sphere, feel free to send an email to me at [email protected]. See you next week!