How colleges can prepare for students with autism

Increasing numbers of young adults with autism are pursuing a college education. Many campuses are not ready for them.

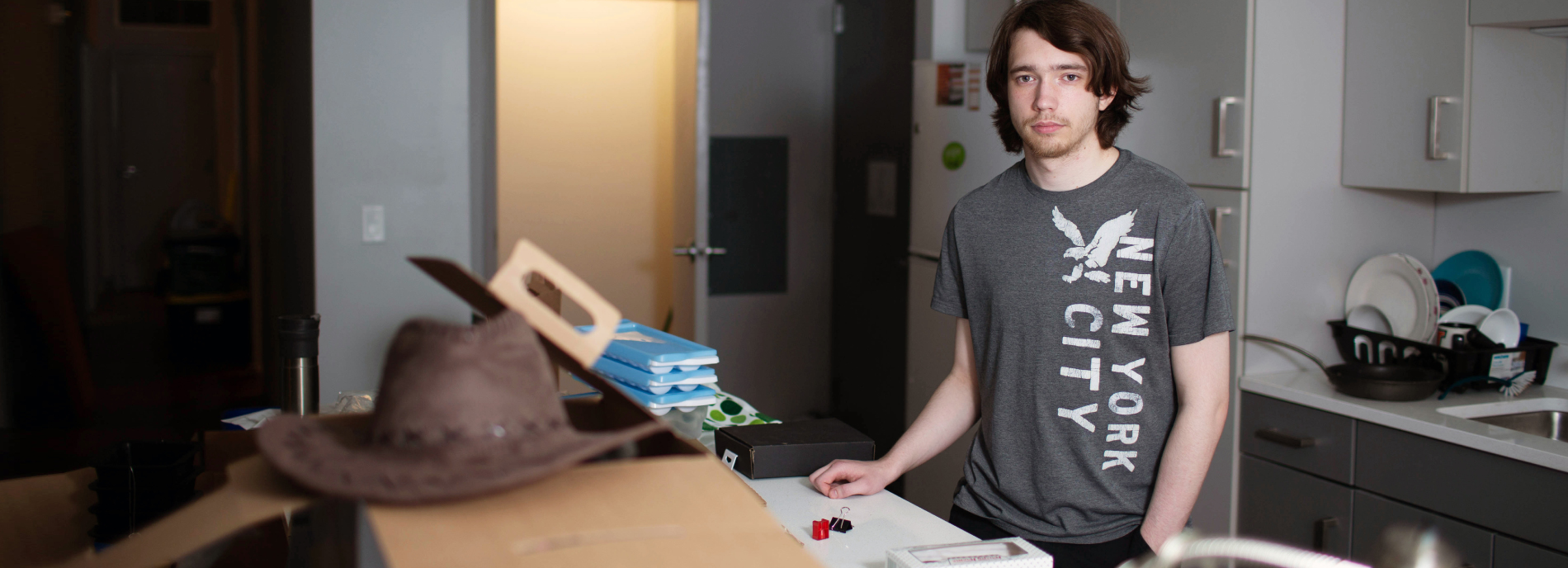

K

ieran Barrett-Snyder was a star student at his high school on Long Island in New York. He had a gift for mathematics and science, and was accepted into all seven of the colleges he applied to. He decided on New York University (NYU), both because it has a strong engineering program and because it is close to his home.During Barrett-Snyder’s first semester in 2014, he did well in all his classes, except for labs that required written reports — a task that felt overwhelming to him. He became so anxious about his workload that at one point he started to feel his heart pounding hard in his chest. “It hurt to lay down,” he recalls.

Barrett-Snyder has autism, and he has felt anxiety for much of his life. But this was more intense than usual. His symptoms persisted for several days, until his mother took him to the emergency room, where he learned he had been having an extended panic attack. He hadn’t taken any psychiatric medications since his most disruptive behaviors had tapered off at around age 9. After the panic attack, though, he started taking pills for anxiety and depression. He also decreased his workload and got on track over the rest of the year.

Then, in his second year at the university, he ended up in a dormitory with two neurotypical students he didn’t connect with, and started avoiding the common area when they were around. One of the suitemates had his girlfriend over all the time, which made Barrett-Snyder even more uncomfortable. He stayed in his room for long stretches, stopped showering and survived on Oreo cookies. It was a vicious cycle: The longer he was in his room, the more self-conscious he felt. “I just felt disgusting most of the time, so I didn’t want to be seen,” he says.

He lost 25 pounds, felt weak and depressed, and was failing several classes. That December, his mother suggested that he take some time off. The only support NYU had offered to him was extended time on tests. “When I approached them about his difficulties,” she recalls, “their response was: ‘Maybe he belongs at a different school.’”

For any young adult, going away to college involves many firsts: the first time living alone, the first time making their own schedule, maybe the first time cooking their own meals. As difficult as this transition is for typical students, it can be especially disorienting for young people on the spectrum, who may also find it difficult to sleep enough, collaborate with others on group projects and advocate for themselves with professors.

Despite those challenges, increasing numbers of young adults with autism have set their sights on a college degree: More than 200,000 students on the spectrum will arrive on campuses around the United States over the next decade, based on statistics from the National Center for Special Education Research and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And for the most part, experts say, these students are entering an educational system that is not ready for them. High school comes with a support system — family at home, therapists nearby, special-education classes — but colleges have traditionally embraced a sink-or-swim mentality.

Under U.S. federal law, college students with disabilities are permitted to receive special accommodations, including extra time on exams and extended deadlines. But these allowances usually fall short of the needs of students with autism. Many students on the spectrum require support that extends beyond the classroom into their social and personal lives, such as reminders to do their laundry regularly or help finding study partners. They also have high rates of anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts, which can worsen in new situations. “Colleges are trying to cope with this expanding mental-health crisis,” says Fred Volkmar, professor of child psychiatry, pediatrics and psychology at Yale University. “They don’t quite know what to do.”

”“Colleges are trying to cope with this expanding mental-health crisis.” Fred Volkmar

College life:

C

reating programs specifically for students with autism is no small commitment. The first such program in the U.S. started in 2002 at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia, and was built up from a successful state-run autism initiative. Nearly two decades later, more than 60 support programs have been launched at two- and four-year colleges around the country. But they vary widely in the services they offer and in their cost, ranging from free up to a few thousand dollars per semester, which students and their families pay on top of tuition.Even with the extra support such programs provide, however, only a minority of people with autism enter college, and even fewer graduate. According to a 2011 study, about 17 percent of young adults with autism enroll in a four-year college, compared with 21 percent of people with learning disabilities and about 40 percent of people with visual or hearing impairments. Among those who attend any type of postsecondary educational institution, including vocational schools and community colleges, only 39 percent earn a degree, compared with 52 percent of typical young adults.

For students with autism, the barriers to graduation are rarely just about grades. More than 75 percent of college students on the spectrum report feeling left out or isolated, and about half have suicidal thoughts, according to a survey of 56 students published in March. Another survey found similar patterns among college students in Australia, who considered anxiety, depression and loneliness to be their greatest challenges. One-third of the Australian students also said they were not getting the academic accommodations they needed.

These difficulties often come as a surprise to students on the spectrum and their families, who may base their expectations on high school performance. Unlike with typical students, solid grades in high school don’t readily predict college success for students with autism. Part of the reason is that special-education programs in schools operate on a ‘success model’: They may boost grades and modify the curriculum to make sure the students graduate. Colleges, by contrast, rely on an ‘equal access’ model, offering the same classes and grading scales to everyone, regardless of ability. College students also lose access to special-education officers, who often provide hours of personalized assistance and tutoring in high school.

“The difference between a success model and an equal-access model is huge — often, families don’t understand that,” says Jane Thierfeld Brown, co-director of College Autism Spectrum in West Hartford, Connecticut, a business that provides counseling services to college-bound young people. Students’ chances of success in college are predicted less by their academic performance in high school, she says, and more by their self-reliance, organizational and planning skills that fall under ‘executive function,’ and work experience — all of which students with autism rarely have.

Some autism programs look specifically for these qualities. Students who apply for the 60 spots at Mercyhurst University in Erie, Pennsylvania, are assessed in a variety of ways, including whether they have demonstrated some level of independence by, for instance, having attended a sleepaway camp or obtained a driver’s license.

Even if the college decides the student is ready, it’s no guarantee of fit. Once they arrive, the students with autism or their parents may hit speed bumps anyway. “Sometimes you have to try again and see if you are happier at the next place,” Brown says.

”“It’s important for the university to be a place where all students have the support they need." Laurie Ackles

Conceal, don’t feel:

T

hat was certainly true for Barrett-Snyder, for whom the classroom had always proved trying. When he was just starting school at age 6, he would get so angry that he would be unable to form words; instead, he would moan and, at times, kick, hit and push other people. Doctors diagnosed him that year with Asperger syndrome. (Asperger syndrome has since been subsumed into the autism diagnosis in the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.”)Barrett-Snyder’s parents took courses on how to handle his tantrums, and he worked with various therapists as he bounced between private and public schools all the way until his graduation from high school at age 18. He excelled academically but didn’t have any close friends. “There was nobody at my high school that I would call my friend,” he says. “They were just strangers that I knew the names of.”

His classmates affectionately compared him to ‘Sheldon,’ the quirky physics prodigy in the television show “The Big Bang Theory.” He spent his free time playing video games and re-watching the Disney movie “Frozen.” He still listens to the soundtrack when he feels depressed, and he likes to quote the lyrics “conceal, don’t feel” from the song “Let It Go.” Last year, his parents gave him a Christmas ornament that features the lead character, Elsa, and plays the song. “I am my family’s Disney princess,” Barrett-Snyder says with a smirk. “One of the things I’ve learned is to own who you are; that’s something I struggled with in the past.”

After he left NYU with failing grades in December 2015, he moved back in with his parents. He spent his days glued to the television. When his mother tried to speak to him, he would just stare into space. If he felt anything at all, he says, it was relief that he didn’t have to do anything. “The major thing about depression is that it’s not about being sad all the time; you wish you could be sad, but you feel nothing,” he says.

As with Elsa, his way out of his ‘emotional winter’ came, in part, thanks to his sister, Grace, who was also diagnosed with Asperger syndrome as a child and is now a software engineer at Google. When he was flailing at NYU, Grace visited and rallied his spirits. And she knew what he felt after he dropped out, too. During her own first semester at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, Grace’s grades were so poor that she was forced to drop out 10 days before final exams. She spent a year studying at a community college, gradually increasing her course load before returning to Smith.

If she could return and succeed in college, she told her brother, he could, too.

In August 2016, Barrett-Snyder arrived on the campus of the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in upstate New York. He got there before the college began its regular semester, to participate in the four-day pre-orientation for the university’s Spectrum Support Program.

Finding support:

R

IT launched the program 10 years ago, including in it many of the key ingredients that can help college students with autism succeed — in particular, assistance with the academic and social transition from high school to college, peer support and career development. As a measure of the program’s success, between 75 and 90 percent of first-year students return for a second year — a rate in line with the 89 percent retention seen in the general student body. The school’s focus on science, technology, engineering and mathematics may help: Students with autism who study these subjects at two-year community colleges are twice as likely to continue and transfer to four-year institutions as their peers with autism who study other subjects.The RIT program has become a model for other programs. It has also made the university a more welcoming place for all students, says social worker Laurie Ackles, the program’s director. “It’s important for the university to be a place where all students who qualify academically have the support they need to be successful,” she says. “Students on the spectrum are coming to college, whether we have the support ready for them or not.”

Ackles is an energetic Rochester native in her early 50s, though her pixie haircut and thick-frame glasses make her look at least a decade younger. She is wandering around the indoor track building, where almost 250 potential employers, mostly technology companies, have set up tables for the university’s career fair. It’s a nerve-wracking time for many RIT students, most of whom can’t graduate unless they spend two semesters and one summer term with a paid, full-time job relevant to their field of study. Studies show that the transition to adulthood and employment is particularly fraught for young people on the spectrum.

Ackles is checking in on the students with autism and giving employers orange buttons that feature a brain illustration and the words “Celebrate Neurodiversity.” Her office spends weeks before the career fair helping students in the autism program develop an elevator pitch, craft a resume and upload a profile onto an online college-recruiting platform. She steers clear of mothering them, she says, but many need someone to check in on them to make sure they have the right clothes to wear to an interview and manage to show up on time. Some of her students have nabbed coveted gigs at Microsoft and Google.

The first student Ackles runs into outside the hall is beaming. Second-year Daniel Porten, nattily dressed in a houndstooth sport coat, has scored an interview for a job working on control systems for trains. He says he is hurrying off to do more research on the company. “That’s a great idea,” she tells him. Another student, who studies 3-D digital design, seems less pleased. She reminds him that the ‘Creative Industry Day’ in March will have more employers that fit his major.

Before RIT’s program began, students with autism could register with the university’s Disability Services Office. Because the university is home to the National Technical Institute for the Deaf, that small office already accommodates more than 1,200 students. It was unequipped to handle the special demands of students with autism who would show up out of the blue during a crisis, or simply drop out. “It was just too much for that office to handle,” Ackles says.

In 2009, the National Science Foundation funded a pilot program at RIT to provide more tailored support to 12 students on the spectrum pursuing degrees in science and technology. The program’s rationale is not to provide counseling or academic advice, Ackles says, but to coach students on how to manage their time, navigate social situations, access services and advocate for themselves. The office has four full-time staff, including Ackles, plus about 20 graduate students and faculty to meet with students on the spectrum as often as twice a week. The team also helps the students find roommates and runs organized activities, including a pre-orientation program for new students, and social events on Friday nights.

When trouble strikes, Ackles is often one of the first to hear about it. Students can contact her at any time — many do — and RIT has an early-alert system that notifies her office if a student is at risk of failing a class. Her students find ingenious ways of getting in trouble, she says. One young man reprogrammed building access cards for his dormitory so that his friends didn’t have to use the intercom to access his floor. Another fell off the roof of a moving car and broke his leg. “I should have brushed the snow off first,” he told Ackles, implying that the car would have been easier to hold on to if his hands hadn’t been slippery and wet. She suggested he not mention that observation at his disciplinary hearing.

As demand for the program increases, Ackles says, she worries about how many students her office can support. Last year, the university accepted 42 students with autism, bringing the total to 90.

Second chance:

I

t took several months before Barrett-Snyder found his groove at RIT, or something close to it.The pre-orientation program was helpful, he says, but even so, his first semester was stressful. Someone on his dorm floor kept vandalizing a white board outside his room, erasing his messages and replacing them with profane phrases. It tortured him. One morning, Barrett-Snyder wrote “Please do not mess with this board.” But of course, he says, “that got messed with.”

He began fantasizing about what he would do if he caught the student in the act. He hoped to land at least one good punch. When he mentioned this in a late-night text to the graduate student assigned to him as a peer coach, the coach asked campus safety to check up on him. The next thing Barrett-Snyder knew, he was being strapped to a gurney and taken to a hospital, where he waited 11 hours to see a psychiatrist. “I finally saw one, and he marked me as not dangerous, and I got to leave,” he says.

If something like that had happened at NYU, he says, it might have broken him. But things were different at RIT. For one thing, he couldn’t lock himself in his room, because Ackles would not have left him alone.

“Kieran — Are you doing okay?” she texted him in early December 2016.

“Yes,” he replied.

She pressed him on his lab reports, which she knew were a weakness. He admitted he hadn’t started working on them. “What’s the plan?” she asked.

“I don’t know. I feel stuck, like I can’t get to the library,” he texted.

“Just take control of your arms and legs 🙂 to collect your materials and walk yourself to the library. The fresh air will feel good,” she texted. “Can you do that?”

He did — and later that year, his grades improved, plus he scored a 16-week work experience for the following semester at an aerospace company in southern California, working on satellite ground software. When he got back on campus in January 2017, he moved into Global Village, a cluster of boxy, modern dormitories.

His new roommates — Logan King, Caleb Katzenstein and Eric Mitchell — didn’t know what to expect.

King, a gangly film major with shoulder-length brown hair with pink highlights, is into science fiction and dressing up as ‘cosplay’ characters in a campus club. Katzenstein studies video-game design and likes to binge watch late-night comedy. Mitchell, the group’s loudmouth, is a music composer with an all-consuming love of baseball. All three also have autism — and living away from home with total strangers had tested them.

Their previous roommate was a “ghost” whose belongings vanished without explanation after a few weeks of classes. “We never saw him,” Mitchell says one snowy February evening, reclining in his usual spot on the communal couch, tearing off a bite from a slice of pizza.

“It was nothing to have a grudge about,” King says. They all felt a tinge of excitement when they first heard that Kieran, whom they had met through the autism program, needed a place to live on campus. He might just become a good friend.

“That’s how Kieran ended up with us,” King says. “This … bundle of joy.”

“Whoa, whoa, I’m many things,” Barrett-Snyder quips, “but they are not joy.” Mitchell erupts in awkward, cartoonish laughter.

The four have an obvious rapport and also usually know when to give one another space. As Kieran dryly puts it, “They are people that I can tolerate.”

Corrections

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that about 10 percent of people with visual or hearing impairments enroll in a four-year college.

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain