Cognition and behavior: Mouse model has autism-like brain

A well-studied mouse model of autism has a smaller-than-normal volume in several autism-associated brain regions.

-

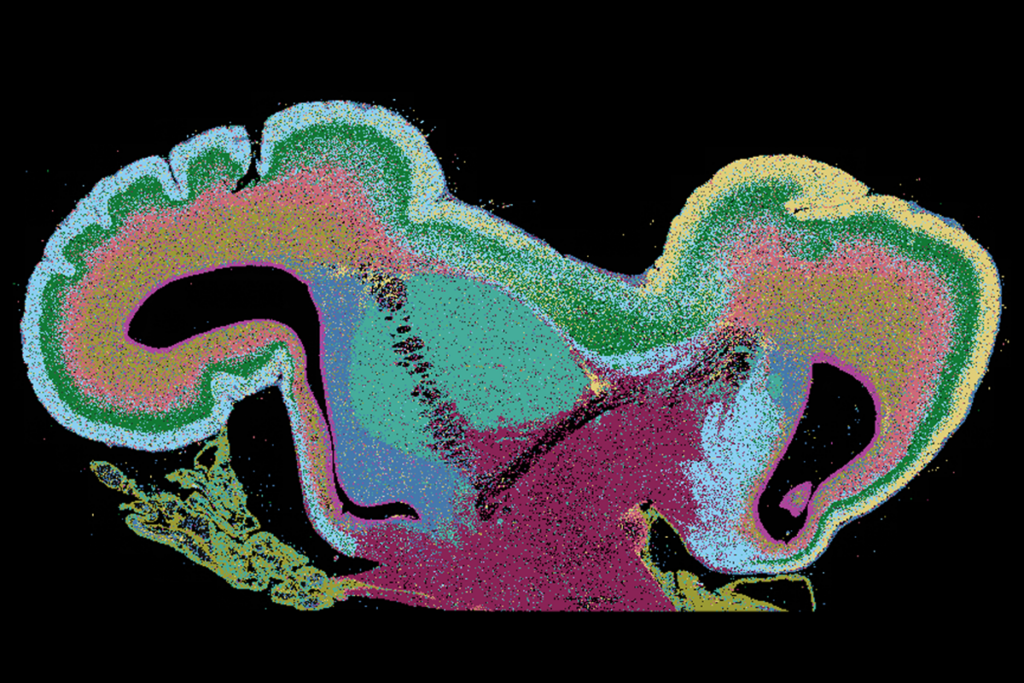

Mouse measures: Mice with an autism-associated mutation have less brain matter (red) than controls in some regions of the corpus callosum (blue), which connects the two sides of the brain.

A well-studied mouse model of autism has a smaller-than-normal volume in several autism-associated brain regions, according to a study published in the October issue of Autism Research1.

The results, which rely on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques typically used in human studies, show that brain abnormalities in the mouse parallel those of people with autism.

A 2003 study identified a single base pair mutation in neuroligin 3, or NLGN3, which functions at the synapse, the junction between neurons, in two Swedish brothers with autism. This has since become one of the best-studied autism-associated mutations and boosted the theory that autism is a disorder of the synapse.

In 2007, researchers created a mouse with the same mutation in NLGN3 and reported that the mice show social deficits similar to those seen in autism. However, another study of the same mouse model did not replicate the results.

One of the challenges in autism research is determining which behavioral assays in mice best approximate human symptoms and replicating these results across laboratories. Studying the neural circuits in these mice can supplement these assays, allowing researchers to pin down the brain abnormalities that underlie autism.

In the new study, researchers compared the brain matter of eight NLGN3 mutant mice with eight controls, using MRI and diffusion tensor imaging, or DTI. DTI detects the rate of water diffusion in the brain and can approximate patterns of neuronal connectivity.

Overall, the brains of the mutant mice have less white and gray brain matter — which contain neuronal projections and their cell bodies, respectively — compared with the brains of controls. In particular, the NLGN3 mutant mice have less gray matter than controls do in the hippocampus, which regulates learning and memory, and the striatum, the reward center of the brain.

The mutant mice also have less white matter than controls do in the corpus callosum. Defects in this region, which connects the brain’s two hemispheres, are associated with autism-like social deficits.

A DTI measure of connectivity was similar in the mutant mice and controls, suggesting that the reduction in brain matter seen by MRI is due to fewer, or immature, neurons in these brain regions.

MRI imaging of mouse mutants could supplement brain imaging studies in people. Human imaging studies are often limited to individuals at the higher-functioning end of the spectrum, who are more likely to cooperate and stay still during the scans, the researchers say.

References:

1: Ellegood J. et al. Autism Res. 4, 368-376 (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Psychedelics research in rodents has a behavior problem

Can neuroscientists decode memories solely from a map of synaptic connections?