Clinical research: Neurexin-1 deletions add to autism risk

Deletions in neurexin-1, a candidate gene for autism, may cause intellectual disability, speech delays, seizures, poor muscle tone and unusual facial features, according to two studies published in the past two months.

Deletions in neurexin-1 (NRXN1), a candidate gene for autism, may cause intellectual disability, speech delays, seizures, poor muscle tone and unusual facial features, according to two studies published in the past two months1, 2.

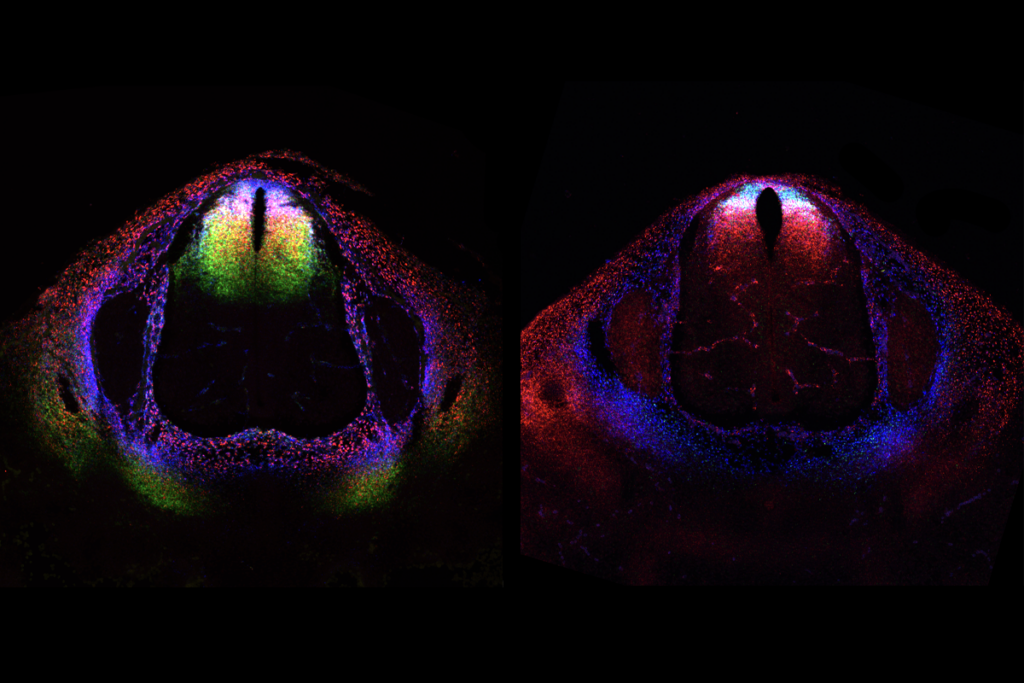

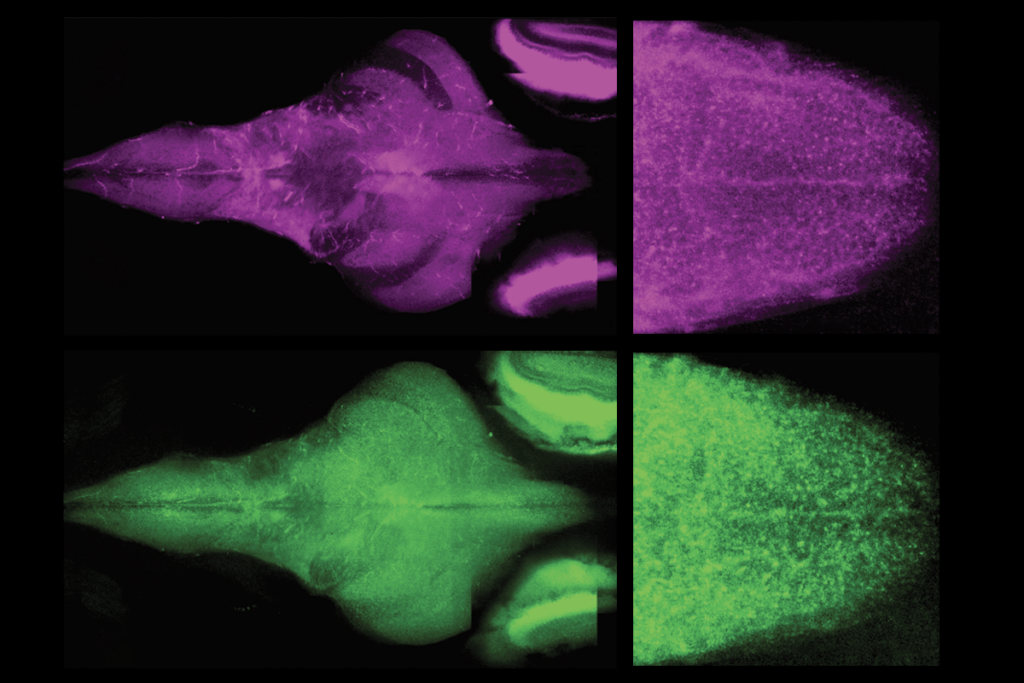

Together, these studies characterize 59 people who have deletions encompassing NRXN1. Proteins in the neurexin family help build and maintain synapses, the junctions between nerve cells. Studies have found deletions in NRXN1 in individuals who have autism.

NRXN1 deletions are rare. In the first new study, published in April in the American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, researchers combed through a database of 30,065 people referred for genetic testing because of intellectual disability or birth defects. They found deletions of varying sizes in 34 people, or 0.11 percent of the group. The researchers had clinical diagnoses for 23 of the people, 10 of whom have autism.

The second study, published 26 March in the American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, looked at 25 people with NRXN1 deletions. The participants came from multiple centers, where they were seen by either a clinical geneticist or a pediatrician.Of the 23 people with detailed clinical information, 15 have autism.

NRXN1 codes for two different protein variants: a longer version called NRXN1-alpha and the shorter NRXN1-beta. The majority of people — 54 of the 59 from both studies — have deletions in NRXN1-alpha.

A study of 32 individuals with NRXN1 deletions, published 7 March in the American Journal of Human Genetics, found that the deletions all cluster near the start of the gene, which codes for NRXN1-alpha3.

Looking closely in this region, the researchers found genetic ‘hotspots’ that are likely to prime it for deletion. These include short repeats that cause the DNA to loop around and bind to itself. When DNA is copied during cell division, the cell’s attempt to fix these loops can result in deletions.

References:

1: Dabell M.P. et al. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 161, 717-731 (2013) PubMed

2: Béna F. et al. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. Epub ahead of print (2013) PubMed

3: Chen X. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 375-386 (2013) PubMed

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles

NIH scraps policy that classified basic research in people as clinical trials