Clinical research: Long-term studies track autism’s trajectory

Two studies published over the past month followed individuals with autism at various ages and showed that they gain developmental skills differently than controls do.

Two studies published over the past monthfollowed individuals with autism at various ages and showed that they gain developmental skills differently than controls do.

The first, a study of high-risk siblings of children with autism, reports that children later diagnosed with autism struggle with language and motor skills between 6 and 36 months of age1. The second followed individuals with the disorderover ten years and found that they improve in their ability function to independently into their late 20s2.

Studies that follow individuals with autism over time may be able to predict how they fare as they get older, and identify the most effective behavioral interventions.

In one of the new studies, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, researchers followed nearly 400 adults and adolescents with autism, ranging between 10 and 52 years of age, at four instances over ten years. The participants are part of the Adolescents and Adults with Autism study, based in Madison, Wisconsin.

The researchers assessed daily living skills using the Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale, a 17-item parent questionnaire. It includes questions that rate an individual’s ability to independently perform tasks such as cooking, making the bed and bathing.

They found that individuals with autism acquire independent living skills through adolescence and into their late 20s. Their improvement plateaus in the 30s and they eventually lose some skills in their 50s. Individuals with both autism and intellectual disability start with lower abilities than those with autism alone and improve less over time, the study also found.

In the other study, published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, researchers followed a group of 204 so-called ‘baby sibs’ of children with autism, who are at a higher-than-typical risk of developing the disorder. At 36 months, 52 of the 204 were diagnosed with autism, 121 were unaffected, and 31 had the broad autism phenotype (BAP), which describes people who show some features of autism, but do not merit a diagnosis.

The researchers assessed the children’s developmental ability at six time points between 6 to 36 months of age, using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning, which has measures for gross and fine motor skills, vision and language.

The researchers then looked for statistically different patterns of development, regardless of whether the children developed autism, and identified four groups.

In one, the ‘developmental slowing’ group, children have average abilities at 6 months of age but have lower cognitive scores at each of the following assessments than the expected norm for that age. This group does not include any unaffected children, but has about 7 percent of those with BAP and 42 percent of children later diagnosed with autism.

In another group, characterized by accelerated development, the children have average abilities at 6 months of age, but gain language and motor skills sooner than average, especially between 18 and 36 months. This group includes only 2 percent of the children later diagnosed with autism, 39 percent of the unaffected children and 16 percent of those diagnosed with BAP.

Children in the third group have early delays in language and motor skills and continue to fall behind in motor ability after 18 months, but their language abilities catch up to typical levels by 36 months. This group includes children from all three categories, with 31 percent of the children with autism, 12 percent of the unaffected children and 45 percent of those diagnosed with BAP.

The fourth, a ‘typical’ category, describes average development and includes 50 percent of the unaffected children, 32 percent of those with BAP and 25 percent of those with autism.

References:

1: Landa R.J. et al. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2012) PubMed

2: Smith L.E. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 51, 622-631 (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

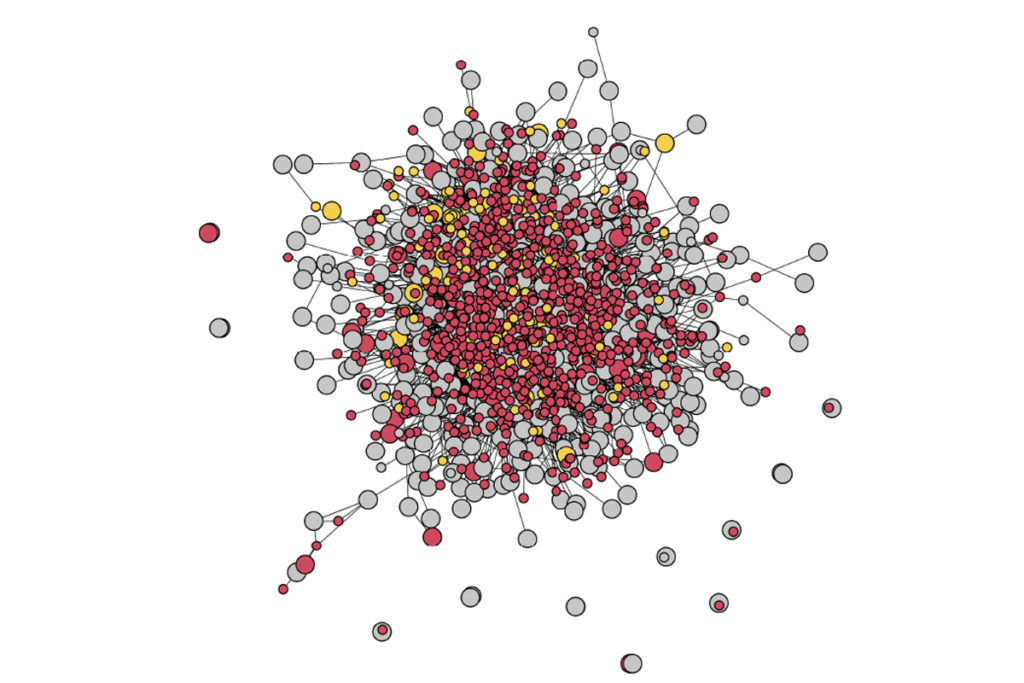

Sequencing study spotlights tight web of genes tied to autism

Targeting NMDA receptor subunit reverses fragile X traits in mice

Maternal infection’s link to autism may be a mirage

Explore more from The Transmitter

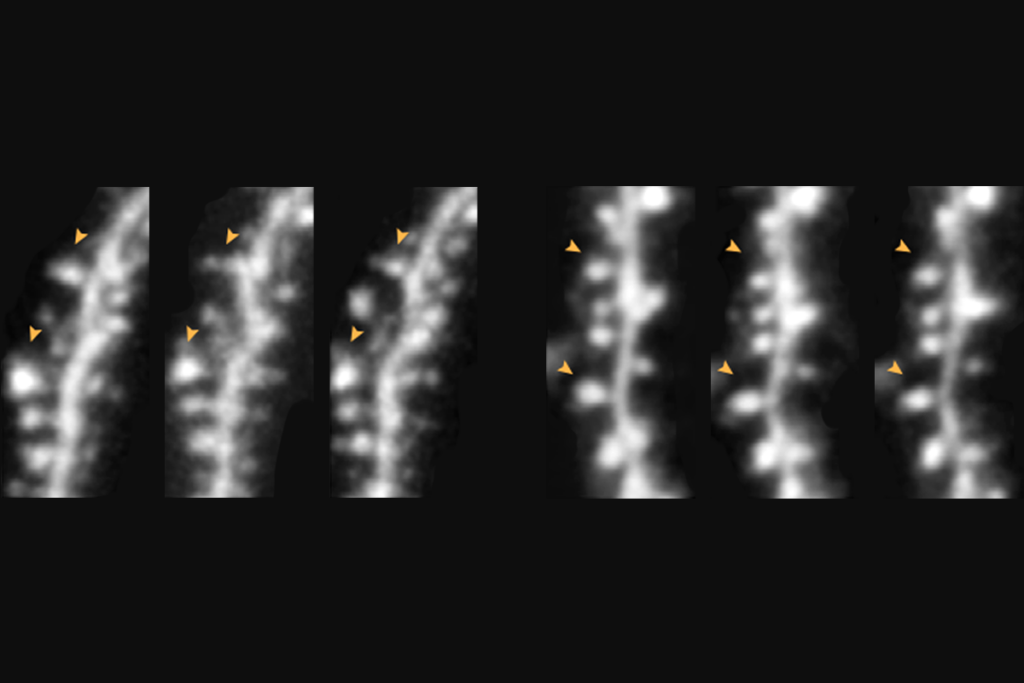

Single-neuron recordings are helping to unravel complexities of human cognition