Class struggles

The psychiatrists who literally write the book on the definitions of mental illness have announced their plan to group all autism spectrum disorders, including Asperger syndrome, under a single category.

The motley mix of abilities and disabilities among individuals with autism is reflected in the long list of their diagnoses: there are, among many others, the classic ‘autistic disorder’, Asperger syndrome — for individuals with strong verbal and cognitive abilities — and ‘pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified’, sort of a catch-all category for people with developmental delay who don’t quite meet the strict criteria for autism.

Last week, the psychiatrists who literally write the book on the definitions of mental illness announced their plan to roll all of these conditions into a single category of ‘autism spectrum disorder.’ It’s one of many major changes they aim to make in the encyclopedic Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), expected to come out in 2013.

This is the fifth edition of the DSM, and revision committees have been meeting for nearly a decade to hash out these changes, which have enormous implications not only for doctors, but for insurance and pharmaceutical industries.

In the current version, DSM-IV, an individual has to meet at least 6 of 16 specific criteria in order to be labeled with ‘autistic disorder’. The DSM-5 draft streamlines these criteria, so that an individual has to meet six of seven criteria to be diagnosed with autism.

At just ten lines, the new classification is elegantly simple. It will undoubtedly make diagnosing autism more straightforward, which, I’d imagine, might lead to greater awareness of the disorder.

The response from the community has been mixed. Some Asperger syndrome advocacy groups are angry at being lumped together with lower-functioning individuals, for instance. Some experts also argue that Asperger syndrome should be listed separately because many of its features — such as onset later in childhood, pedantic communication style and active but odd social interactions — are clinically distinct from autism.

All of this means that the DSM committees will have much to discuss when they review public comments about the proposed revision, available online until April 20.

I can understand why people with Asperger syndrome may feel angry, or at least puzzled, about the official description of their condition becoming less specific. But the new definition is probably a truer reflection of the genetic and neurobiological similarities between individuals with all forms of autism.

Perhaps more important, emphasizing that the disorder is a wide spectrum — one that places articulate professors and musical savants next to children who flap their hands and cower from others — may help combat the stigma associated with autism.

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

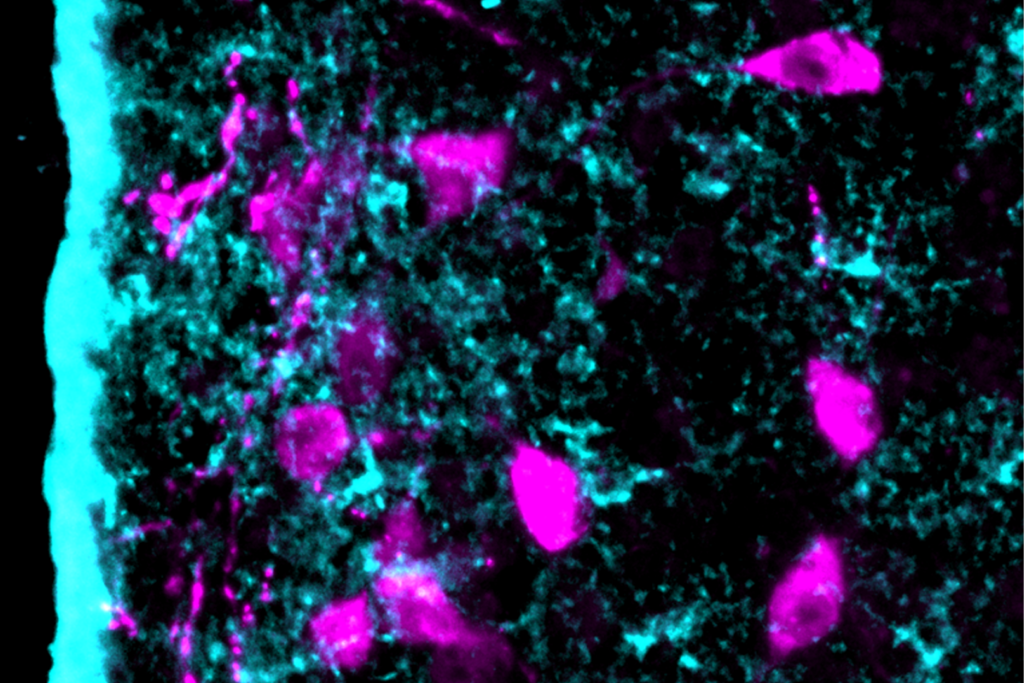

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Securing the academic pipeline amid uncertain U.S. funding climate

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers